Notes on and quotations from Stuart Hall

"If the black subject and black experience are not stabilised by Nature or by some other essential guarantee, then it must be the case that they are constructed historically, culturally, politically - and the concept which refers to this is 'ethnicity'."

|

1979 |

Catherine Barret met Stuart Hall on a march at Aldermaston. They married in 1964. Catherine is a social historian who has written a book about the freeing of slaves in Jamaica. Stuart watched

"someone who is English become inward with another culture. She knows more about Jamaica than I do. It has been a fantastic experience, watching her journey." Hall and Adams 2007

From Hall and Adams 2007:

"I think you always need the double perspective. Before you say that you have to understand what it is like to come from that "other" place. How it feels to live in that closed world. How such ideas have kept people together in the face of all that has happened to them. But you also have to be true to your own culture of debate and you have to find some way to begin to translate between those two cultures. It is not easy, but it is necessary."

Hall first encountered the nuances of such conversations at his home in Kingston when he was growing up. He was born into a middle-class family in thrall to what he calls 'the colonial romance'. People think all Jamaicans are black, he suggests, and don't understand the gradations that can exist within a single family like his.

" My mother's connections to England were more recent. My father's side was not pure African either, it had Indian in it, and probably some English somewhere. I was always the blackest member of my family and I knew it from the moment I was born. My sister said: "Where did you get this coolie baby from?" Not black baby, you will note, but low-class Indian."

His mother's maiden name was Hopwood and she once suggested to her son that she thought she might have some Habsburg blood in her. 'I mean: craziness,' he says, laughing. He believes cultural studies was born for him when he was first told he could not bring black school friends home, even though, to white eyes, he was black himself.

"It was the subaltern position, on the knees to the dominant culture. After the war you could hear the voices in Kingston whispering "independence, independence independence". I could not understand why my family was not part of that."

Hall's sister was crushed by that mentality; she fell in love with a black medical student but was barred from seeing him by her mother; after a breakdown she had electric shock treatment and has never had another relationship.

"She stayed at home. She looked after my mother, and my father, then my brother who was blind, until they died.' His sister's life is, he says, 'one of the reasons I have never been able to write about or think about the individual separate from society. The individual is always living some larger narrative, whether he or she likes it or not."

I was born in Jamaica, and grew up in a middle-class family. My father spent most of his working life in the United Fruit Company. He was the first Jamaican to be promoted in every job he had; before him, those jobs were occupied by people sent down from the head office in America. What's important to understand is both the class fractions and the colour fractions from which my parents came. My father's and my mother's families were both middle-class but from very different class formations.

My father belonged to the coloured lower-middle-class. His father kept a drugstore in a poor village in the country outside Kingston. The family was ethnically very mixed-African, East Indian, Portuguese, Jewish. My mother's family was much fairer in colour; indeed if you had seen her uncle, you would have thought he was an English expatriate, nearly white, or what we would call 'local white'. She was adopted by an aunt, whose sons - one a lawyer, one a doctor, trained in England. She was brought up in a beautiful house on the hill, above a small estate where the family lived.

Culturally present in my own family was therefore this lower-middle-class, Jamaican, country manifestly dark skinned, and then this lighter-skinned English-oriented, plantation-oriented fraction, etc.

So what was played out in my family, culturally, from the very beginning, was the conflict between the local and the imperial in the colonized context. Both these class fractions were opposed to the majority culture of poor Jamaican black people: highly race and colour conscious, and identifying with the colonizers.

I was the blackest member of my family. The story in my family, which was always told as a joke, was that when I was born, my sister, who was much fairer than I, looked into the crib and she said, 'Where did you get this coolie baby from?' Now 'coolie' is the abusive word in Jamaica for a poor East Indian, who was considered the lowest of the low. So she wouldn't say 'Where did you get this black baby from?', since it was unthinkable that she could have a black brother. But she did notice that I was a different colour from her. This is very common in coloured middleclass Jamaican families, because they are the product of mixed liaisons between African slaves and European slave-masters, and the children then come out in varying shades.

So I always had the identity in my family of being the one from the outside, the one who didn't fit, the one who was blacker than the others, 'the little coolie', etc. And I performed that role throughout. My friends at school, many of whom were from good middle-class homes, but blacker in colour than me, were not accepted at my home. My parents didn't think I was making the right kind of friends. They always encouraged me to mix with more middle-class, more higher-colour, friends, and I didn't. Instead, I withdrew emotionally from my family and met my friends elsewhere. My adolescence was spent continuously negotiating these cultural spaces.

I went to a small primary school, then I went to one of the big colleges. Jamaica had a series of big girls' schools and boys' schools, strongly modelled after the English public school system. We took English high school exams, the normal Cambridge School Certificate and A-level examinations. There were no local universities, so if you were going to university you would have to go abroad, off to Canada, United States or England to study. The curriculum was not yet indigenized. Only in my last two years did I learn anything about Caribbean history and geography. It was a very 'classical' education; very good, but in very formal academic terms. I learned Latin, English history, English colonial history, European history, English literature, etc. But because of my political interest, I also became interested in other questions. In order to get a scholarship you have to be over eighteen and I was rather younger, so I took the final A-level exam twice, I had three years in the sixth form. In the last year, I started to read T.S.Eliot, James Joyce, Freud, Marx, Lenin and some of the surrounding literature and modern poetry. I got a wider reading than the usual, narrowly academic British-oriented education. But I was very much formed like a member of a colonial intelligentsia.

From Hall, S. and Phillips, C. 1997

"I was brought up in a family which for peculiar, historical reasons had a very rosy relationship to the mother country. Most of my life had been spent thinking that the apogee of scholarly work and education was to get a scholarship and go to England to be finished off, and then come back, as it were, civilized. A good proportion of my life as a schoolboy was spent in the study of English literature, romantic poets, British history and so on. When I came to England in 1951 I came by boat. I arrived in Bristol and took an early autumn journey from Bristol to Oxford, and I thought, I know this place, I know everything about this place, it's absolutely completely familiar".

"I arrived in Oxford on a Rhodes scholarship, more or less straight from school in Jamaica, in 1951. I would say that my politics were principally 'anti-imperialist'. I was sympathetic to the left, had read Marx and been influenced by him while at school, but I would not, at the time, have called myself a Marxist in the European sense. In any event, I was troubled by the failure of orthodox Marxism to deal adequately with either 'Third World' issues of race and ethnicity, and questions of racism, or with literature and culture, which preoccupied me intellectually as an undergraduate." (Hall, S. 2010, p.179)

|

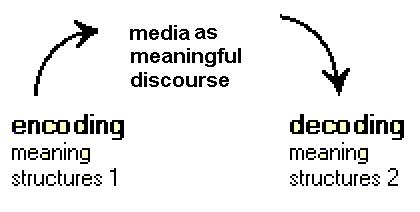

Coding and de-coding

encoding A 'raw' historical event cannot, in that form, be transmitted... the event must become a 'story' before it becomes a communicative event The 'message form' is the necessary 'form of appearance' of the event in its passage from source to receiver (p. 129)

[The 1955 Paris Match cover analysed by Roland Barthes is a message form. The photographer was seeking an image that conveyed an idea. In a similar way, a television news programme creates stories in the forms it uses.]

decoding Before this message can have an 'effect'... it must first be apropriated as meaningful discourse and be meaningfully decoded. Clearly, what we have labelled in the diagram 'meaning structures 1' and 'meaning structures 2' may not be te same.

[The 1955 Paris Match cover is interpreted (decoded) differently by Roland Barthes and our imaginary Oxford scholar]

|

|

From

Michèle Barret 1998:

1979 Stuart Hall moved to the Open University... revolutionised the sociology curriculum by junking the 'founding fathers' and reconceptualising the core mainstream of the subject in terms of the historical rise and decline of Western modernity, and by introducing major courses in cultural studies, whose focus is representation, signification, identity and cultural difference Michèle Barret says that signification refers to the way "meanings are created by a double action" involving "written or spoken words, or images", such as an advertisement or fashionable clothes, "that provide us with a kind of raw material for our senses". Then, we "have to interpret or understand this raw material ... as meaning something. We usually interpret the word or image automatically, "without giving it a second thought, with the meanings appearing as natural and inevitable". However, "the term signification tells us that the bond between raw material (the 'signifier') and meaning (the 'signified') is much weaker than it seems, and that they are pasted together in different ways at different times by different societies, cultures and sub-cultures"

|

"The Great Moving Right Show"

Gramsci insisted that we get the "organic" and "conjunctural" aspects of the crisis into a proper relationship. What defines the "conjunctural" - the immediate terrains of struggle - is not simply the given economic conditions, but precisely the "incessant and persistent" efforts which are being made to defend and conserve the position. If the crisis is deep -" organic" - these efforts cannot be merely defensive. They will be formative: a new balance of forces, the emergence of new elements, the attempt to put together a new "historical bloc", new political configurations and "philosophies", a profound restructuring of the state and the ideological discourses which construct the crisis and represent it as it is "lived" as a practical reality; new programmes and policies, pointing to a new result, a new sort of "settlement" - "within certain limits". These do not "emerge": they have to be constructed. Political and ideological work is required to disarticulate old formations, and to rework their elements into new configurations. The "swing to the Right" is not a reflection of the crisis: it is itself a response to the crisis.

...

Race constitutes another variant, since in recent months questions of race, racism and relations between the races, as well as immigration, have been dominated by the dialectic between the radical - respectable and the radical-rough forces of the Right. It was said about the 1960s and early 70s that, after all, Mr. Powell lost. This is true only if the shape of a whole conjuncture is to be measured by the career of a single individual. In another sense, there is an argument that "Powellism" won: not only because his official eclipse was followed by legislating into effect much of what he proposed, but because of the magical connections and short- circuits which Powellism was able to establish between the themes of race and immigration control and the images of the nation, the British people and the destruction of "our culture, our way of life". I would be happier about the temporary decline in the fortunes of the Front if so many of their themes had not been so swiftly reworked into a more respectable discourse on race by Conservative politicians in the first months of this year

"Notes on Deconstructing 'the Popular,'" pp. 227-39 from People's History and Socialist Theory, edited by R. Samuel. London: Routledge,

... The people versus the power-bloc: this, rather than "class-against- class", is the central line of contradiction around which the terrain of culture is polarised. Popular culture, especially, is organised around the contradiction: the popular forces versus the power-bloc. This gives to the terrain of cultural struggle its own kind of specificity. But the term "popular", and even more, the collective subject to which it must refer -- "the people" -- is highly problematic. It is made problematic by, say, the ability of Mrs Thatcher to pronounce a sentence like, "We have to limit the power of the trade unions because this is what the people want." That suggests to me that just as there is no fixed content in the category of "popular culture", so there is no fixed subject to attach to it -- "the people". "The people are not always back there, where they have always been, their culture untouched, their liberties and their instincts intact, still struggling on against the Norman yoke or whatever: as if we can "discover" them and bring them back on stage, they will always stand up in the right appointed place and be counted. The capacity to constitute classes and individuals as a popular force -- that is the nature of political and cultural struggle: to make the divided classes and the separate peoples -- divided and separated by culture as much as by other factors -- into a popular-democratic cultural force.

... Popular culture is one of the sites where this struggle for and against a culture of the powerful is engaged: it is the stake to be one or lost in that struggle. It is the arena of consent and resistance. It is partly where hegemony arises, and where it is secured. It is not a sphere where socialism, a socialist culture -- already fully formed -- might be simply "expressed". But it is one of the places where socialism might be constituted. That is why "popular culture" matters. Otherwise, to tell you the truth, I don't give a damn about it.

Stuart Hall, 1988: "New Ethnicities" in Black Film British Cinema. British Film Institute/Institute for Contemporary Arts, Document 7. [Based on an ICA Conference, February 1988] pages 27 to 31

(¶1) I have centred my remarks on an attempt to identity and characterise a significant shift that has been going on (and is still going on) in black cultural politics. This shift is not definitive, in the sense that there are two clearly discernible phases - one in the past which is now over and the new one which is beginning - which we can neatly counterpose to one another. Rather, they are two phases of the same movement, which constantly overlap and interweave. Both are framed by the same historical conjuncture and both are rooted in the politics of anti-racism and the post-war black experience in Britain. Nevertheless I think we can identify two different 'moments' and that the difference between them is significant.

(¶2) It is difficult to characterise these precisely, but I would say that the first moment was grounded in a particular political and cultural analysis. Politically, this is the moment when the term 'black' was coined as a way of referencing the common experience of racism and marginalisation in Britain and came to provide the organising category of a new politics of resistance, among groups and communities with, in fact, very different histories, traditions and ethnic identities, in this moment, politically speaking. 'The black experience', as a singular and unifying framework based on the building up of identity across ethnic and cultural difference between the different communities, became 'hegemonic' over other ethnic/racial identities - though the latter did not, of course, disappear. Culturally, this analysis formulated itself in terms of a critique of the way blacks were positioned as the unspoken and invisible 'other' of predominantly white aesthetic and cultural discourses.

(¶3) This analysis was predicated on the marginalisation of the black experience in British culture; not fortuitously occurring at the margins, but placed, positioned at the margins, as the consequence of a set of quite specific political and cultural practices which regulated, governed and 'normalised' the representational and discursive spaces of English society. These formed the conditions of existence of a cultural politics designed to challenge, resist and, where possible, to transform the dominant regimes of representation - first in music and style, later in literary, visual and cinematic forms. In these spaces blacks have typically been the objects, but rarely the subjects, of the practices of representation. The struggle to come into representation was predicated on a critique of the degree of fetishisation, objectification and negative figuration which are so much a feature of the representation of the black subject. There was a concern not simply with the absence or marginality of the black experience but with its simplification and its stereotypical character.

(¶4) The cultural politics and strategies which developed around this critique had many facets, but its two principal objects were: first the question of access to the rights to representation by black artists and black cultural workers themselves. Second, the contestation of the marginality, the stereotypical quality and the fetishised nature of images of blacks, by the counter-position of a 'positive' black imagery. These strategies were principally addressed to changing what I would call the 'relations of representation'.

(¶5) I have a distinct sense that in the recent period we are entering a new phase. But we need to be absolutely clear what we mean by a 'new' phase because, as soon as you talk of a new phase, people instantly imagine that what is entailed is the substitution of one kind of politics for another. I am quite distinctly not talking about a shift in those terms. Politics does not necessarily proceed by way of a set of oppositions and reversals of this kind, though some groups and individuals are anxious to 'stage' the question in this way. The original critique of the predominant relations of race and representation and the politics which developed around it have not and cannot possibly disappear while the conditions which gave rise to it - cultural racism in its Dewesbury form - not only persists but positively flourishes under Thatcherism. 1 There is no sense in which a new phase in black cultural politics could replace the earlier one Nevertheless it is true that as the struggle moves forward and assumes new forms, it does to some degree displace, reorganise and reposition the different cultural strategies in relation to one another. If this can be conceived in terms of the 'burden of representation', I would put the point in this form: that black artists and cultural workers now have to struggle, not on one, but on two fronts. The problem is, how to characterise this shift - if indeed, we agree that such a shift has taken or is taking place - and if the language of binary oppositions and substitutions will no longer suffice. The characterisation that I would offer is tentative, proposed in the context of this essay mainly to try and clarify some of the issues involved, rather than to pre-empt them.

(¶6) The shift is best thought of in terms of a change from a struggle over the relations of representation to a politics of representation itself. It would be useful to separate out such a 'politics of representation' into its different elements. We all now use the word representation, but, as we know, it is an extremely slippery customer. It can be used, on the one hand, simply as another way of talking about how one images a reality that exists 'outside' the means by which things are represented: a conception grounded in a mimetic theory of representation. On the other hand the term can also stand for a very radical displacement of that unproblematic notion of the concept of representation. My own view is that events, relations, structures do have conditions of existence and real effects, outside the sphere of the discursive; but that it is only within the discursive, and subject to its specific conditions, limits and modalities, do they have or can they be constructed within meaning. Thus, while not wanting to expand the territorial claims of the discursive infinitely, how things are represented and the 'machineries' and regimes of representation in a culture do play a constitutive, and not merely a reflexive, after-the- event, role. This gives questions of culture and ideology, and the scenarios of representation - subjectivity, identity, politics - a formative, not merely an expressive, place in the constitution of social and political life. I think it is the move towards this second sense of representation which is taking place and which is transforming the politics of representation in black culture.

(¶7) This is a complex issue. First, it is the effect of a theoretical encounter between black cultural [p.28] politics and the discourses of a Eurocentric, largely white, critical cultural theory which in recent years, has focused so much analysis of the politics of representation. This is always an extremely difficult, if not dangerous, encounter. (I think particularly of black people encountering the discourses of post-structuralism, postmodernism, psychoanalysis and feminism.) Second, it marks what I can only call 'the end of innocence', or the end of the innocent notion of the essential black subject. Here again, the end of the essential black subject is something which people are increasingly debating, but they may not have fully reckoned with its political consequences. What is at issue here is the recognition of the extraordinary diversity of subjective positions, social experiences and cultural identities which compose the category 'black'; that is, the recognition that 'black' is essentially a politically and culturally constructed category, which cannot be grounded in a set of fixed trans-cultural or transcendental racial categories and which therefore has no guarantees in nature. What this brings into play is the recognition of the immense diversity and differentiation of the historical and cultural experience of black subjects. This inevitably entails a weakening or fading of the notion that 'race' or some composite notion of race around the term black will either guarantee the effectivity of any cultural practice or determine in any final sense its aesthetic value.

(¶8) We should put this as plainly as possible. Films are not necessarily good because black people make them. They are not necessarily 'right-on' by virtue of the fact that they deal with the black experience. Once you enter the politics of the end of the essential black subject you are plunged headlong into the maelstrom of a continuously contingent, unguaranteed, political argument and debate: a critical politics, a politics of criticism. You can no longer conduct black politics through the strategy of a simple set of reversals, putting in the place of the bad old essential white subject, the new essentially good black subject. Now, that formulation may- seem to threaten the collapse of an entire political world. Alternatively, it may be greeted with extraordinary relief at the passing away of what at one time seemed to be a necessary fiction. Namely, either that all black people are good or indeed that all black people are the same. After all, it is one of the predicates of racism that 'you can't tell the difference because they all look the same'. This does not make it any easier to conceive of how a politics can be constructed which works with and through difference, which is able to build those forms of solidarity and identification which make common struggle and resistance possible but without suppressing the real heterogeneity of interests and identities, and which can effectively draw the political boundary lines without which political contestation is impossible, without fixing those boundaries for eternity. It entails the movement in black politics, from what Gramsci called the 'war of manoeuvre' to the 'war of position' - the struggle around positionalities. But the difficulty of conceptualising such a politics (and the temptation to slip into a sort of endlessly sliding discursive liberal-pluralism) does not absolve us of the task of developing such a politics.

(¶9) The end of the essential black subject also entails a recognition that the central issues of race always appear historically in articulation, in a formation, with other categories and divisions and are constantly crossed and recrossed by the categories of class, of gender and ethnicity. (I make a distinction here between race and ethnicity to which I shall return.) To me, films like Territories, Passion of Remembrance, Mv Beautiful Laundrette and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid, for example, make it perfectly clear that this shift has been engaged; and that the question of the black subject cannot be represented without reference to the dimensions of class, gender, sexuality and ethnicity.

Difference and Contestation

(¶10) A further consequence of this politics of representation is the slow recognition of the deep ambivalence of identification and desire. We think about identification usually as a simple process. structured around fixed selves' which we either are or are not. The play of identity and difference which constructs racism is powered not only by the positioning of blacks as the inferior species but also, and at the same time, by an inexpressible envy and desire; and this is something the recognition of which fundamentally displaces many of our hitherto stable political categories, since it implies a process of identification and otherness which is more complex than we had hitherto imagined.

(¶11) Racism, of course, operates by constructing impassable symbolic boundaries between racially constituted categories, and its typically binary system of representation constantly marks and attempts to fix and naturalise the difference between belongingness and otherness. Along this frontier there arises what Gayatri Spivak calls the 'epistemic violence' of the discourses of the Other - of imperialism, the colonised, Orientalism, the exotic, the primitive, the anthropological and the folk-loric. 2 Consequently the discourse of anti-racism had often been founded on a strategy of reversal and inversion, turning the 'Manichean aesthetic' of colonial discourse upside-down. However, as Fanon constantly reminded us, the epistemic violence is both outside and inside, and operates by a process of splitting on both sides of the division - in here as well as out here. That is why it is a question, not only of 'black-skin' but of 'Black-Skin, White Masks' - the internalisation of the self-as-other. Just as masculinity always constructs femininity as double - simultaneously Madonna and Whore - so racism constructs the black subject: noble savage and violent avenger. And in the doubling, fear and desire double for one another and play across the structures of otherness, complicating its politics.

(¶12) Recently I have read several articles about the photographic text of Robert Mapplethorpe - especially his inscription of the nude, black male - all written by black critics or cultural practitioners. 3 These essays properly begin by identifying in Mapplethorpe's work the tropes of fetishisation, the fragmentation of the black image and its objectification, as the forms of their appropriation within the white, gay gaze. But, as I read, I know that something else is going on as well in both the [p.29] production and the reading of those texts. The continuous circling around Mapplethorpe's work is not exhausted by being able to place him as the white fetishistic, gay photographer; and this is because it is also marked by the surreptitious return of desire - that deep ambivalence of identification which makes the categories in which we have previously thought and argued about black cultural politics and the black cultural tcxt extremely problematic. This brings to the surface the unwelcome fact that a great deal of black politics, constructed, addressed and developed directly in relation to questions of race and ethnicity, has been predicated on the assumption that the categories of gender and sexuality would stay the same and remain fixed and secured. What the new politics of representation does is to put that into question, crossing the questions of racism irrevocably with questions of sexuality. That is what is so disturbing, finally, to many of our settled political habits about Passion of Remembrance. This double fracturing entails a different kind of politics because, as we know, black radical politics has frequently been stabilised around particular conceptions of masculinity, which are only now being put into question by black women and black gay men. At certain points, black politics has also been underpinned by a deep absence or more typically an evasive silence with reference to class.

(¶13) Another element inscribed in the new politics of representation has to do the question of ethnicity. I am familiar with all the dangers of 'ethnicity' as a concept and have written myself about the fact that ethnicity, in the form of a culturally constructed sense of Englishness a particularly closed, exclusive arid regressive form of English national identity, is one of the core characteristics of British racism today. 4 I am also well aware that the politics of anti-racism has often constructed itself in terms of a contestation of 'multi-ethnicity' or 'multi-culturalism'. On the other hand, as the politics of representation around the black subject shifts, I think we will begin to see a renewed contestation over the meaning of the term 'ethnicity' itself.

(¶14) If the black subject and black experience are not stabilised by Nature or by some other essential guarantee, then it must be the case that they are constructed historically, culturally, politically - and the concept which refers to this is 'ethnicity'. The term ethnicity acknowledges the place of history, language and culture in the construction of subjectivity and identity, as well as the fact that all discourse is placed, positioned, situ-and all knowledge is contextual. Representation is possible only because enunciation is always produced within codes which have a history, a position within the discursive formations of a particular space and time. The displacement of the 'centred' discourses of the West entails putting in question its universalist character and its transcendental claims to speak for everyone, while being itself everywhere and nowhere. The fact his grounding of ethnicity in difference was deployed, in the discourse of racism, as a means of disavowing the realities of racism and repression not mean that we can permit the term to be permanently colonised. appropriation will have to be contested, the term disarticulated from its position in the discourse of 'multi-culturalism' and transcoded, just as we previously had to recuperate the term 'black' from its place in a system negative equivalences. The new politics of representation therefore also sets in motion an ideological contestation around the term, 'ethnicity'. But in order to pursue that movement further, we will have to re-theorise the concept of difference.

(¶15) It seems to me that, in the various practices and discourses of black cultural production, we are beginning to see constructions of just such a conception of ethnicity: a new cultural politics which engages rather than suppresses difference and which depends, in part, on the cultural construction of new ethnic identities. Difference, like representation, is also a slippery, and therefore, contested concept. There is the 'difference' which makes a radical and unbridgable separation: and there is a 'difference' which is positional, conditional and conjunctural, closer to Derrida's notion of differance, though if we are concerned to maintain a politics it cannot be defined exclusively in terms of an infinite sliding of the signifier. We still have a great deal of work to do to decouple ethnicity, as it functions in the dominant discourse, from its equivalence with nationalism, imperialism, racism and the state, which are the points of attachment around which a distinctive British or, more accurately, English ethnicity have been constructed. Nevertheless, I think such a project is not only possible but necessary. Indeed, this decoupling of ethnicity from the violence of the state is implicit in some of the new forms of cultural practice that are going on in films like Passion and Handsworth Songs. We are beginning to think about how to represent a non- coercive and a more diverse conception of ethnicity, to set against the embattled, hegemonic conception of 'Englishness' which, under Thatcherism, stabilises so much of the dominant political and cultural discourses, and which, because it is hegemonic, does not represent itself as an ethnicity at all.

(¶16) This marks a real shift in the point of contestation, since it is no longer only between anti-racism and multi-culturalism but inside the notion of ethnicity itself. What is involved is the splitting of the notion of ethnicity between, on the one hand the dominant notion which connects it to nation and 'race' and on the other hand what I think is the beginning of a positive conception of the ethnicity of the margins, of the periphery. That is to say, a recognition that we all speak from a particular place, out of a particular history, out of a particular experience, a particular culture, without being contained by that position as 'ethnic artists' or film- makers. We are all, in that sense, ethnically located and our ethnic identities are crucial to our subjective sense of who we are. But this is also a recognition that this a not an ethnicity which is doomed to survive, as Englishness was, only by marginalising, dispossessing, displacing and forgetting other ethnicities. This precisely is the politics of ethnicity predicated on difference and diversity.

(¶17) The final point which I think is entailed in this new politics of representation has to do with an awareness of the black experience as a diaspora experience, and the consequences which this carries [p.30] for the process of unsettling, recombination, hybridisation and 'cut-and-mix' - in short, the process of cultural diaspora-isation (to coin an ugly term) which it implies. In the case of the young black British films and film- makers under discussion, the diaspora experience is certainly profoundly fed and nourished by, for example, the emergence of Third World cinema; by the African experience; the connection with Afro-Caribbean experience; and the deep inheritance of complex systems of representation and aesthetic traditions from Asian and African culture.

Dreaming Rivers Martina Artille |

But, in spite of these rich cultural 'roots', the new cultural politics is operating on new and quite distinct ground - specifically, contestation over what it means to be 'British'. The relation of this cultural politics to the past; to its different 'roots' is profound, but complex. It cannot be simple or unmediated. it is (as a film like Dreaming Rivers reminds us) complexly mediated and transformed by memory, fantasy and desire. Or, as even an explicitly political film like Handsworth Songs clearly suggests, the relation is inter-textual - mediated, through a variety of other 'texts'. |

There can, therefore, be no simple 'return' or 'recovery' of the ancestral past which is not re-experienced through the categories of the present: no base for creative enunciation in a simple reproduction of traditional forms which are not transformed by the technologies and the identities of the present. This is something that was signalled as early as a film like Blacks Britannica and as recently as Paul Gilroy's important book, There Ain't No Black in the Union Jack. 5 Fifteen years ago we didn't care, or at least I didn't care, whether there was any black in the Union Jack. Now not only do we care, we must.

(¶18) This last point suggests that we are also approaching what I would call the end of a certain critical innocence in black cultural politics. And here, it might be appropriate to refer, glancingly, to the debate between Salman Rushdie and myself in the Guardian some months ago. The debate was not about whether Handsworth Songs or The Passion of Remembrance were great films or not, because, in the light of what I have said, once you enter this particular problematic, the question of what good films arc, which parts of them are good and why, is open to the politics of criticism. Once you abandon essential categories, there is no place to go apart from the politics of criticism and to enter the politics of criticism in black culture is to grow up, to leave the age of critical innocence.

(¶19) It was not Salman Rushdie's particular judgement that I was contesting, so much as the mode in which he addressed them. He seemed to me to be addressing the films as if from the stable, well-established critical criteria of a Guardian reviewer. I was trying perhaps unsuccessfully, to say that I thought this an inadequate basis for a political criticism and one which overlooked precisely the signs of innovation, and the constraints, under which these film-makers were operating. It is difficult to define what an alternative mode of address would be. I certainly didn't want Salman Rushdie to say he thought the films were good because they were black. But I also didn't want him to say that he thought they weren't good because 'we creative artists all know what good films are', since I no longer believe we can resolve the questions of aesthetic value by the use of these transcendental, canonical cultural categories. I think there is another position, one which locates itself inside a continuous struggle and politics around black representation, but which then is able to open up a continuous critical discourse about themes, about the forms of representation, the subjects of representation, above all, the regimes of representation. I thought it was important, at that point, to intervene to try and get that mode of critical address right, in relation to the new black film-making. It is extremely tricky, as I know, because as it happens, in intervening, I got the mode of address wrong too! I failed to communicate the fact that, in relation to his Guardian article I thought Salman was hopelessly wrong about Handsworth Songs, which does not in any way diminish my judgement about the stature of Midnight's Children, I regret that I couldn't get it right, exactly, because the politics of criticism has to be able to get both things right.

(¶20) Such a politics of criticism has to be able to say (just to give one example) why Mv Beautiful Laundrette is one of the most riveting and important films produced by a black writer in recent years and precisely for the reason that made it so controversial: its refusal to represent the black experience in Britain as monolithic, self-contained, sexually stabilised and always 'right-on' - in a word, always and only 'positive', or what Hanif Kureishi has called, 'cheering fictions':

"the writer as public relations officer, as hired liar. If there is to be a serious attempt to understand Britain today, with its mix of races and colours, its hysteria and despair, then, writing about it has to be complex. It can't apologise or idealise. It can't sentimentalise and it can't represent only one group as having a monopoly on virtue"." (Hanif Kureishi, 'Dirty washing', Time Out, 14-20 November 1985.)Laundrette is important particularly in terms of its control, of knowing what it is doing, as the text crosses those frontiers between gender, race, ethnicity, sexuality and class. Sammy and Rosie is also a bold and adventurous film, though in some ways less coherent, not so sure of where it is going, overdriven by an almost uncontrollable, cool anger. One needs to be able to offer that as a critical [p.31] judgement and to argue it through, to have one's mind changed, without undermining one's essential commitment to the project of the politics of black representation.

|

Hall, S. 1997 (Editor) Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, London; Sage in association with the Open University |

Top of

Page

Top of

Page

Andrew Roberts likes to hear from users:

To contact him, please

use the Communication

Form