Cosy Corners in Depression and War

Autobiography of Joan Hughes

The story of one person's nests

My father came home for a few days at the end of 1942 [1941??], and received a bombshell as soon as Christmas was over. My mother and I were told to leave our one room accommodation, as the landlady said she required the room for a Morrison shelter. We could hardly believe her, when she said that she wanted the front room for a Morrison shelter. Since war broke out there had been no bombs in Lawford or in Manningtree. In Mistley three landmines had fallen, slightly damaging Edme Maltings but no lives had been lost. This had been an isolated incident; no-one felt in much danger from air-raids in our stretch of countryside on the Essex-Suffolk borders. Because we lived near the coast, there was more likelihood of invading troops, but I never thought about this possibility. It was not spoken about and was unthinkable. The sea-shore had been barred to visitors for the duration of the war, a disappointing feature especially from children's point of view, as a visit to the flat sands of Dovercourt was remembered as a very pleasant pre-war experience. In the meantime, we visited the banks of the tidal River Stour, where there were two patches of sand separated by an interesting stretch of marsh. The road next to this was known as the Manningtree Walls. On the sandy stretch near Mistley was a well-maintained paddling and swimming pool. Sea-gulls were always present here and their cries, whenever I hear them bring back nostalgic memories. One day I was standing next to the shallow end of the swimming pool which I sometimes entered though I could not swim, as the water only reached my waist, and lost my balance, toppled over backwards and plunged head-first into the pool. I was preparing to lift myself out when I was helped by a stranger with a car, who kindly helped me out with my blue check summer dress soaking wet, but I was quite unhurt. This man insisted in taking me home in his car. My mother thanked him and I thought how lucky I was . In those days everyone in the village seemed kind. Around here I was no longer nervous of strangers but would go anywhere and talk to anyone.

[Anderson and Morrison shelters] In London where many bombs had fallen, Morrison shelters were unpopular, at least in West Kensington and Fulham. Anderson shelters in the back gardens were below ground, and in my experience felt safe, as there was a good layer of earth over us. Morrison shelters were considered of little protection, as they were above-ground, within living-rooms. The accepted wisdom in most family houses was that the safest place was in the cupboard under the stairs, if people were caught indoors during a sudden air-raid. In the Essex countryside Anderson shelters had not been supplied; apparently people could apply for a Morrison shelter if they so wished, but our landlady was the first person we heard about to do so.

My parents could smell a rat. What crossed their minds was that the objection was to the fact that instead of a mother and daughter occupying the room during Christmas week 1941 there had been a married couple, my parents. My landlady probably took a dim view of finding a strange man in the house.

The fear was unjustified. In his youth my father had been somewhat of a tearaway, going out for boisterous week-end drinking bouts; but now he was in his early forties and a Lance-Corporal in the Army; had given up drinking and behaved very quietly when on leave. I felt that my mother and I were being treated very unfairly, because within a week my father would be away again in the North of England and would not visit for at least three months, and then only for a week-end. My mother was very tired of having to keep packing up and moving on. I did not like it very much; we had to find somewhere else in the same village and this was a problem.

In the January of 1942 my mother talked to people in the village, and met the young wife of one of the assistant managers at Edme Maltings. She occupied No: 1 Edme Villas; it was in the largest house in a row of twelve houses supplied by Edme for its senior staff. Not so many people bought their own houses in those days. Mrs Broom was about ten years younger than my mother and got on well with her, and offered to share the house with my mother for the rest of the war. The understanding was that my father would not visit and we agreed to this. Mrs Broom had no children, her husband reputedly a brilliant young man with a University degree was in the Forces overseas and she did not expect to see him again until the end of the war. My mother accepted this as her best option. When we moved in, we found that we were left on our own for many weeks, as Mrs Broom stayed with other relations and visited her own house only occasionally. I liked Mrs Broom and she let me use her husband's books. There was a book on German, and as our school taught this language, I decided to have a look at it during the school holidays. I spent the time learning German alphabet and script, but never learnt any vocabulary or grammar. It fascinated me just to copy the old-fashioned German lettering, which I believe has been superseded.

When I went back to school I found I had been put in the stream who did science and not German, so I forgot about the German language henceforth.

I enjoyed life in Edme Villas. It was a detached house. We had two rooms and a share of the kitchen. After a few weeks Mrs Broom decided to let her own apartments to another soldier's wife, Mrs Snailham. We not did see much more of Mrs Broom, who trusted Mrs Snailham to look after the house. These young women were out at work, so I saw them only in the evenings and at week-ends. Mrs Snailham kept to herself during the week, which was just as well for my mother and I, for I had homework to do, while my mother had the housework after her day's work at the Apple Farm. It was a quiet contented life.

One day I decided to ask my mother about sex. She declined to discuss

it with me and suggested that I should go and talk to

Mrs Snailham

about

it. I liked Mrs Snailham but was too nervous to broach this subject with

her. I was rather unhappy and disturbed about it. The biology teacher

declined to teach the reproductive system of mammals. We had lessons on all

parts of the human anatomy, given by the gym teacher, except for the sexual

parts; there was something too inhibited, repressive and Victorian about

this attitude. One day I blew up and said to my mother "You are Victorian"

but did not explain what I meant. In Scripture lessons some of the girls

were asking "Was Mary a Virgin?" and this was also disturbing. They did not

talk about what they meant by this to me. I had received some sexual

information from a very rough girl in the playground in London; but could

find no-one to discuss the subject clearly.

I decided that I did not want to get married and would concentrate on

school work, and getting a good career. This was what most girls did at our

school. It was an easy option. We did not meet boys at school, and the

older ones went into the Army at eighteen.

This I am told is how they keep

priests on a celibate course of life; by segregating them in a seminary for

five to seven years from age 18 to 25. In these modern times this system is

breaking down, because the priests found it very hard to communicate with

women an a normal social basis when they began work in a parish and had to

visit families. This is the subject of a recent TV programme on "Catholics

and Sex". Though in my teens I was not a practising Catholic, yet much the

same attitude was observed in our Girls' school, even though it was not a

church school.

| Starting 23.11.1992 on Channel Four, Catholics and Sex, a mini- series examining the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church on sex and how they affect ordinary Catholics, presented by Kate Saunders and Peter Stanford. |

In the village I met a girl of fourteen called Joan; it was someone I had played with while at the secondary modern school. There were a group of girls gossiping and Joan left the group to climb a tree, for we were walking along a field footpath. Someone said, "She has done something wrong; she is going to have a baby?" "What will happen to her?" I asked. "She will be all right," they said. In village life these things were not spoken about but Joan 's baby was probably brought up as her younger sister. There was still a good community spirit in such villages, neighbours, friends and the extended families of relations who never moved far away to work all helped each other. Wartime experience was beginning to break down networks, but here in Lawford, Manningtree and Mistley they were still intact.

In the first months of 1942, with a more settled home life, I was beginning to do very well at school. I always suffered from some lack of confidence because I was a year behind my age-group, and when I scored well in examinations I asked myself "Is this really because I'm clever, or is it because as I am older than the rest, it is easier for me to do well?"

This attitude persisted until my last two years in school when age difference seemed to matter less. One of the problems of being a thirteen year old in a class where most were eleven or twelve was the fact that I was having periods, and I knew most of the others did not. The lavatories were not provided with bins for the disposal of used towels, which had to be carried home, wrapped in paper in the same bag as my books. Greyfriars school was meant for those aged from five to twelve-plus.

Nevertheless I felt more at home in Form Upper Four D than I had in Lower Four D. Now I was placed with those of more or less equal academic ability, and the work was more demanding. I was not teased so much for being a soldier's daughter, a school free dinner girl, and a Londoner.

In the playground I still talked to some of the girls I had met in

Lower Four D. Two of them I remember clearly. They were mild-mannered and

not very bright. I asked them if they minded not passing exams and they

said they did not. One was freckled with red hair and the other very plump

and placid. But half way through January they disappeared and only the

plump girl returned just before Easter. "Where is Roberta?" I asked. Doreen

replied somewhat matter-of factly "She died. We both had pneumonia. I got

better." In those days young people still died from pneumonia; this

information saddened me. "I'm lucky", said the plump girl "to be well, and

I've just going to get on with life." "What subjects do you like?" "I can

pass in English. I like reading" she said. She was one of those who left

school at fourteen to work in a shop or as a junior in a Colchester office.

I was sad that Roberta, the very attractive redhead had died. I had

been reading in the newspaper that there were new drugs called

sulphonamides which were called magic bullets. They were the

first drugs

used to treat pneumonia before the penicillins appeared. I don't know if

they were available to the public at the time of Roberta's illness. Since

then much patient laboratory work has been put into developing a wide range

of antibiotics. We are very fortunate that they have been widely available

since the National Health Service came into being in Britain. We called the

sulphonamides M. and B. tablets in the 1940's; as we knew little science

and found it hard to pronounce the word sulphonamide.

I found a book about

Marie Curie

in the travelling library. This gave

details not only of how Marie discovered new chemical radioactive

compounds, but how much work she did to promote their use in the treatment

of cancer in her later life. But it was a long time before these were to be

effective in treating the disease without harming the patient. The book

inspired me and I worked hard at science, even though we had few

opportunities for this in the Girls' School. The subject we did was called

General Science and occupied two periods per week, whereas I knew that in

the boys' school six periods were devoted to the separate subjects of

chemistry, physics and biology.

The journey to school from Lawford to Colchester took half an hour on

the normal buses. The school bus driver was nick-named Banger and completed

the journey within twenty minutes. There were about ten stops on the way.

When the bus arrived in Lawford it already carried children from the

outlying village Brantham, which was on the other side of the river Stour

in Suffolk, and from Mistley and Manningtree. About five children would be

on the bus when it reached Lawford, where a major contingent got on.

However no-one of my age attending my school got on the bus at Lawford; the

Lawford contingent were mostly younger children . This was one reason for

my loneliness during holidays when my cousin John was not staying in

Lawford. One small boy of eleven I caught smoking a cigarette as he

alighted from the bus, and I told him off. He was the rector's son. But he

took little notice of me. He was the only one I ever saw smoking. The bus

carried boys attending the grammar and technical schools and girls

attending the Convent and Art schools in Colchester, besides our little

group for the Girl's High School. The first interesting feature we passed

was Rachel's house. She occupied a room in front of the house, and as a

past student at the Girls' High School waved to the school bus. We waved

back, always feeling sorry for this invalid, and as I had received lessons

from her, I regarded her with much affection.

When we had passed the oldest part of Lawford, containing Lawford

Place, and a few thatched cottages and the "Alms-houses", we came to the

Land Settlement. This was a row of large detached houses on each side of

the country road, surrounded by glass-houses, with a few fields belonging

to each. The plots were quite small; these people made their living from

market gardening. Land settlement people had originally come here from

towns in the thirties; it was the idea to give a few unemployed people

small plots of land, so they would have some work. It was not expected that

they would earn more than a meagre living; however by 1940, the settlers

between Lawford and Colchester had become prosperous. Many of their

children had passed the eleven-plus examinations entitling them to Grammar

School education; about half a dozen of these joined our school bus.

There were not many more stops before we reached Colchester and the bus

used to speed along, passing a plantation of about a dozen very tall trees

with all their slender branches pointing towards the sky, planted in a

straight row behind the grass verge of the road. When I saw a postcard of

the famous painting showing a straight road with tall trees on each side, I

recalled this stretch of road on the way to Colchester, and wondered if

these trees were planted in imitation of the painting. We did not stop in

Rowhedge, the nearest village on the outskirts of Colchester, because

people living here were able to use Colchester Town Transport Authority

buses. The bus stopped in Colchester bus park at ten minutes to nine, which

gave everyone time to walk to their respective schools in time for Assembly

starting at nine o'clock.

At the end of the summer term in 1942 I found I had obtained

first-class results in nearly all school subjects, failing only in music

and physical education. These last two subjects were not tested but school

reports by the teachers were given.

As a relaxation from academic work, I enjoyed art. I was very fortunate

that I had been given some real artists' water- colours by my father. Most

of our possessions from our London house had been lost, but he had brought

a few interesting oddments back from London before he went into the Army.

Just before I finished the summer term in 1942, I painted the

horsechestnut tree in the playground. This would be the last time I would

see it. Next term I was due to enter the Middle Fifth Form in the senior

part of the school situated in North Hill, Colchester, near the train

station, and not far from the cattle market and the school sports fields.

For the school holidays I brought all my school books home according to

the school custom. Next term we would return them to be collected and

exchanged for next years' books. The teachers did not like to leave any

school books in the school during the school holidays. Only books belonging

to those pupils who had been taken ill and missed the ending of term were

packed up and stored. It was quite a heavy load to carry on last day of

term.

When I got home I put the books away in a cupboard, determining not to

look at them until the long six weeks' summer holiday was over. It was my

custom to work long hours during term-time but to do no school work during

the holidays. I spent as much time as possible out-of-doors and roamed the

fields, picking blackberries, gathering mushrooms, or simply walking with

village children or with my cousin John, who usually spent a week or two in

Lawford during August.

Some of the girls from the High School I would not see again. About one

quarter of the girls left school to start work at the age of fourteen. A

large number of these were girls who were poor academic achievers and who

preferred to leave. One of these was Doreen, who had joined in the teasing

about "free dinner girls". I learned that she had started work in

hairdressing. It did not attract me, but my mother's eldest brother was a

hairdresser with his own business, and the richest member of my mother's

family. I did not guess that young girls starting work in this trade

received rather poor pay, but I was glad it was not me. I had some desire

to become a schoolteacher if possible, as I thought our teachers had a nice

life, but wished to avoid nursing as I hated hospitals. Even the smell of

the disinfectant used to frighten me. Nursing, teaching or staying at

school to enter University were the three careers recommended for High

School Girls, and the teachers deplored the fact that some girls left at

fourteen. Parents had entered a contract to keep their daughters on until

the age of 16; and in my case it would have to be 17, as I was a late

starter, in order to enter for the School Certificate Examination, which

was supposed to open the way to us for good career opportunities. None of

our teachers was married, so this possibility was not discussed. At any

rate, teachers expected girls to have a good few years in a suitable career

before thinking of marriage. Before the second world war, women were not

allowed to continue work in careers such as teaching when they married.

Fortunately some of these absurd rules were demolished by wartime

conditions. Even in our Girls' High School, a young married woman teacher

to assist in the teaching of physical education was taken on before the war

was over.

After the summer holidays I started school again on a different site.

This was North Hill School which contained the Lower, Middle and Upper

Fifth Forms and two years of the Sixth Form. I walked down the hill to

school, and back up it to reach the bus park in the evenings. We walked up

a long drive to reach the school entrance. The gardens at the back

contained tennis courts and a netball pitch.

I remained unable to do well in the gymnasium or at games; though in my

spare time I got plenty of exercise by walking, cycling and gardening. It

was a lack of co-ordination that prevented me catching or hitting balls;

and nervousness that prevented me from jumping over "horses". I did not

worry too much about it.

Another difficulty at the school was the fact that coffee blancmange

made me feel sick. We were required to eat everything on our plates. When

coffee blancmange was on the menu, which I could see in advance, I used to

miss lunch completely. In spite of wartime rationing, I don't remember

being hungry. Bread was unrationed until after the war ended, when the

severity of rationing increased. In 1942, the meat ration was still

adequate, and points rationing, introduced at Christmas 1941 was not too

severe. Points rationing included such items as tins of sardines, and most

tinned food. We had one pound of jam each every month, and the sweet ration

was larger than I had been accustomed to eating in pre-war days. Chips

could be bought off the ration, and restaurant meals were never included in

the ration. We could not afford to eat in cafes or restaurants; but this

meant that school meals were not included in our ration. The girls no

longer brought sandwiches to school, as everybody wished to take advantage

of this. So when I missed lunch in order to avoid the chocolate blancmange,

I did not feel too hungry. There was another tactic I had adopted in regard

to the blancmange. I simply did not go up to the serving tables when the

sweet was being given out. But unfortunately I was moved to a table

directly under the teachers table, and felt unable to do anything else than

completely miss the meal. This passed unnoticed because lunch was taken in

two relays. The half of the girls not taking lunch remained for

three-quarters of an hour in the school grounds. As there was always

someone in the grounds, no-one noticed that I had remained out there for

one and a half hours at lunchtime.

Otherwise life continued in comfortable routine. I was now studying

Latin with Miss Burchby, a woman who appeared to be about seventy, who

would have been retired if it had not been wartime, when there was a

desperate shortage of labour and everybody had a job. Married women without

young children were required by law to take work by 1942, and men up to age

41 were being called up for the Army, unless they were in occupations

regarded as essential.

I met some new teachers at North Hill; was now in Lower 5 A. The form

mistress, Miss Chapman also taught French. Miss Chapman liked me; we did

not do much spoken French; but Miss Chapman praised my French composition.

Consequently, I enjoyed the French lessons. Maths was also very well taught

by Miss Phillips, an Oxford Graduate. Many of these senior grammar school

teachers had been graduates of Oxford or Cambridge; had never married, as

the assumption in those days was that one either had a career or marriage.

The new generation of teachers moving into the schools would never again be

like these teachers. I usually got top marks in Maths, English composition

and French. However, English literature I found more difficult, as it

required analyses of the characters of the people in the novels and the

plays, which I found difficult. Nevertheless I did all subjects moderately

well, and was considered one of those likely to obtain "matriculation".

This was a grade awarded to those who achieved at least a certain standard

called a credit in English, one foreign language and mathematics and at

least two other subjects. We were told if we did not get a credit in Latin

we could not go to University. I learned later on after I left school that

this rule had only been true for Oxford or Cambridge. University was

something I dared not hope for at this time. None of the girls were

confident of going to university, even those who did very well in exams.

The war may have been responsible for this. We were told by Miss Chapman

our Form teacher that it was unfortunate that we were having our secondary

education in war-time, as we were missing all the clubs and social life

that used to be available in the school in the evenings. I did not care too

much about this; was afraid it was something for which money had to be

found, and that I would have been left out of it anyway. I could not

imagine what was meant by clubs and social life, and whatever I was missing

did not seem attractive. In my spare time I loved country walks, visiting

my great-aunts, seeing my cousin John, and became fond of dogs. John used

to bring his pet dog Gyp to Lawford sometimes, and I was delighted to stoke

her and admire her beautiful black fur, and wish I had one like her.

Occasionally I spent a day in Ipswich with Aunt Betty and cousin John

and not only saw Gyp but also John's pet tortoise. I would dash out into

the garden at No:1 Grange Road, Ipswich where John lived to see how far the

tortoise had walked along the path. I was convinced that it would take a

whole year for the tortoise to complete his walk!

Sometimes John and I went for walks on our own to Alexandra Park. When

we did this we pretended we were going on a great adventure, though the

park was only ten minutes walk from the house. In fact we did very

dangerous things, which we never told any adults about. There was an

underground shelter round the four sides of Alexandra Park. It was disused

but contained bunks. John knew where the entrance was situated, and we

squeezed inside. At first there was a dim light coming from the entrance,

but further on the darkness was complete. There was a passage running along

one wall. The other wall was lined with bunks and we clung on to the bunks,

walking forwards until we could see the light at the other end of the

rectangular tunnel. John usually saw this light two or three minutes before

I did, for I was short-sighted and did not wear glasses. I think I made the

circuit of the shelter two or three times at the age of thirteen or

fourteen before I outgrew such "adventures". Perhaps even more

reprehensible was the day we broke into a small factory, deserted on a

Sunday. We did not touch anything; simply liked to stare at the strange

machines. A small back door was left unlocked in this factory which backed

on to the park.

At other times in Lawford John and I were content to play on a

home-made see-saw, made from a plank of wood some builders had left near a

pile of sand and cement. Their work had been abandoned. We balanced the

see-saw on a pile of concrete blocks. John weighed only six stone, when I

weighed eight stone in early teen-age. By the age of eighteen I still

weighed only eight and a half stone; had become much slimmer on the

war-time diet. But in early teen-age, I was overweight. Consequently John

had to place two bricks on his side of the see-saw to balance our weights,

enabling us to rock backwards and forwards contentedly for an hour or more.

These were brief relaxations in a life of hard school work.

It sounds as though I was having a very quiet life, hardly knowing

there was a war on. We had stopped carrying our gas-marks to school.

Somehow confident that by the autumn of 1942 we would not be invaded by

Germans. I was following the war by reading my grandmother's newspaper when

I visited her at the week-end. The Russians were keeping Hitler's troops

occupied, but by the look of the sketch-maps, appeared to be doing badly.

Kharkov and Kiev had been occupied by the Germans since 1941, though they

had retreated from the outskirts of Moscow, but they had advanced to the

borders of Stalingrad, now called Volgagrad. The battle of Stalingrad was

the first sign of victory for the allies. We thought that the Russians had

done wonders in preventing the Germans from taking this town, though as yet

the Germans were holding on near its borders. Then came the victory of the

British under General Montgomery at El Alamein. This made us feel that the

tide of the war had turned in our favour. Not long afterwards the Allied

Armies of the British and the Americans advanced through North Africa,

defeating Rommel, and the Russians began making some progress and chased

the Germans away from Stalingrad and much of occupied Russia during January

and February 1943. These were the events I was reading about on the front

page of my grandmother's Daily Express. I became a collector for Mrs

Churchill's Aid to Russia fund in my spare time, and was pleased to visit

from door to door, collecting small contributions, and at the large houses

larger amounts. I was not afraid to go up to the "gentry's " houses, large

detached houses belonging to the owners of local firms, such as Parsons the

builder and ask for funds. But school work kept my mind occupied most of

the time.

But personal sadness was coming for my mother. In the Autumn 1942, her

mother was diagnosed as having stomach cancer. She was 71. No operation was

suggested. I do not know why, whether the cancer was too far advanced or

whether it was not customary to operate on the over-70's in those days.

Certainly the average treatment was never so successful as it has become in

post-war days. My mother said "We have to move to Gordona, so that I can

look after Nana" "I don't want to go. Edme Villas is nice and I want to

stay here," I said. I had been living there almost a year and felt settled

down. I liked

Mrs Snailham, who stayed

there at week-ends, and I liked

reading Bob Broom's books. But we had to go. Accordingly my mother moved in

to Gordona just before Christmas 1942 and occupied the front bedroom, while

I had the little box-room. Nana remained in her customary back bedroom,

which was of an equal size to the front one, and contained a large double

bed, with brass fittings at top and bottom. Nana was as yet not too ill,

and was able to eat meals, but spent most of her time in bed. Mother had to

prepare for Christmas, as we wished to invite relations as usual.

For Christmas, John was put into the box bedroom. I shared a double bed

in the front room with Aunt Betty, John's mother. My mother moved a single

bed into Nana's room, and slept in the same room as her. Christmas was not

so festive this year, with Nana lying ill, but we put a brave face on it.

Aunt Kate with Aunt Annie visited for Christmas dinner, they were the

only ones to attend church that Christmas. John and I declared that Nana

was sure to get better. This seemed to be proved when she came downstairs

and sat in a chair and helped by peeling the vegetables. This was a brave

effort. She had to rest again after a couple of hours. But all the

relations tried to make it a good Christmas for my cousin John and myself.

My father did not come home for Christmas 1942. He had received one

stripe by Christmas 1941, when I told him that "One stripe was not much

good. You should be a sergeant." After eighteen months in the army he had

two stripes and was now a Corporal, and managed to take 48 hours leave

shortly after Christmas 1942, when I sewed on his second stripe.

|

'Rybarvin', a bronchodilator solution containing

adrenaline and atropine methonitrate used for more

than 40 years which was delivered by hand-held nebuliser. The first

"inhaler" to be made in the UK. You poured the liquid into the top of the

inhaler, screwed on the nozzle and repeatedly squeezed a rubber bulb and

breathed in the spray that came out. One user (14 years old) said

"sometimes I would fall asleep with it in my mouth (too much exertion) and

it would stain my lips brown, It sort of worked, but took ages and if you

had a chest infection as well, then it didn't work at all and out would

come the doctor, give you an injection which promptly made you vomit and

vomit! I dreaded it,,,!! Although it did clear the lungs somewhat, but was

so violent."

1944 - September 1944 - Christmas 1944 - Spring1945 - end of 1945 - winter 1945/1946 - trip in 1946 - summer 1946 - Joan 1947 - Winter 19471948 - July 1948: Gladys died aged 51 on 9.7.1948 following an injection for the relief of asthma - Joan's asthma 1985 |

She still had a part-time job at the "Apple Farm". Stocks of apples were stored here all the year and dispatched to shops in the towns when ordered. The apples had to be graded and packed. This was indoor, regular work which suited my mother. She put most of her earnings into her Post Office Account, as the army allowance had been increased when my father was promoted to Corporal and was sufficient to live on. She received an allowance for me, and I continued to receive free travel to school and free school dinners. I also received five pounds per term clothes allowance from the age of fourteen, and this went into my own Post Office Savings Account, my mother declaring that for the time being, she would buy my clothes. Clothes purchases were few and far between. I had to have new underclothes, a blouse or two, and one new school summer dress, but that was about all. Mother said that when the war was over, she would buy some good clothes with her savings. She often mentioned that she would like a "beaver lamb" coat. This was a coat made of lambswool, dyed to look like a coat made of beaver fur. In those imitation fur coats were popular with the less well off, like ourselves.

I never thought that fur coats represented cruelty to animals in those days, but did not like guns. I was lucky to grow up in a part of the country where there was no pheasant shooting or fox hunting. Unfortunately by 1984 that had changed. One day I was visiting my father and as we were approaching Manningtree station, I remarked to a man in the train that I did not like to see a line of men walking across the field beating the grass to make the pheasants rise. "Its only sport," he said , as if that explained everything.

| O almighty God, and heavenly Father, we glorify thee that thou hast again fulfilled to us thy gracious promise, that, while the earth remaineth, seed-time and harvest shall not fail. We bless thee for the kindly fruits of the earth, which thou hast given to our use. (Book of Common Prayer) |

Nana was being given pain-killing drugs and spent more and more of her time asleep. Eventually she was spending most of her day in bed. By June that year she was eating very little, We went to the fruit-shop in Manningtree and bought grapes and peaches for her; at this time these were luxury fruits bought only for the sick. I would go up to her bedroom and take her a peach, and became worried when she said very little. All Nana said when I gave her a peach was "Fruits of the Earth". "She is very ill now," said my mother. When Dad came home on Sunday, he took me aside and said "Your grandmother will die soon." "I don't believe it," I said. But Aunt Kate said the same thing.

July came. I sat for the end of term exams and got over 70% marks for Latin, French and History and Literature. In science , mathematics and English language I gained over 85% marks and was very pleased with my results. Aunt May came to stay at Gordona for a few days, and helped me revise for my end-of-term exams by testing me in Latin. She held the translation, while I read from the text in Latin, translating it into English. "I don't think much of that," said Aunt May. "You have learnt the translation by heart." "That's what the teacher encourages us to do," I replied. "Latin is a dead language , which nobody speaks. I don't think it does us much good to learn it. But we have to, for School Certificate".

I was more interested in French, where I could translate unknown texts far more easily. In French I did not learnt anything by heart, except lists of irregular verbs and poetry in French. Barbara was the best student of French in our class. She soon became able to take French novels home and read them in French without translating, which was something that I could never do. But she was hopeless at mathematics. Barbara had to learn all the proofs of the geometry theorems of Euclid by heart in order to pass her exams. But I never had to do that, and regarded mathematics as a very easy subject. I said to Barbara, "Maths is something where one can reason out the answers. We don't have to remember them. Barbara then asked me to help her.

One Saturday morning early in July, the first runners beans of the season was were ready to pick. I picked a full basket of beans that morning and spent some time earthing up the potatoes. Then I got the deck-chairs out; we had only two. To my surprise Nana had got up and dressed and came out into the garden. She sat on a straight-backed kitchen chair. She had a knife in her hand and a bowl on her lap. She started cutting up the runner beans. My mother and I sat in deck-chairs on each side of Nana, luxuriating in the July sunshine. "Nana", I said, "you are getting better." "No", she said "I wanted to get up even though I'm in a lot of pain." "But you're doing so well," I said.

When she had finished the beans and put them in the bowl ready for a final rinse and for cooking, Nana got up and walked half way down the garden. She went behind the garage and looked at the water-butt kept to catch water dripping off the garage roof, and she looked at the jam-jars full of beer, hanging up to catch the wasps. These had been placed there by Uncle Bob, and they were things to which I objected, as I thought they looked nasty and that it was cruel to drown the wasps in this way. I had never been stung by one, and always said that if one kept very still, when they approached, they would never sting. This was the only feature in Nana's garden which I did not like. But at the present moment, I was far more interested in what Nana was doing than in the wasps. Nana walked further down the garden and looked at the apple tree, and the rows of potatoes. Then tired from this effort , she came back to sit in the garden chair.

"You must have some nice runners beans today for dinner", I said. "No, I can't eat them", said Nana. "Then why were you cutting them up?" "I was doing them for you. I was so glad to be able to do something." Then Nana went indoors and went to bed again in the little box-room. In the afternoon I took her a cup of tea and a peach, and was disappointed to hear that she had not been able to eat any dinner. Aunt Kate came to call on her that afternoon. I told Aunt Kate that she was getting better as she had got up and walked down the garden. Aunt Kate said "What she is doing is going round for the last time and saying good-bye to all that she knew". My mother agreed with Aunt Kate. I said, "She won't die. She's getting better," because that was what I wanted to believe.

In the middle of August John came to stay, as was his usual custom. But this year he said he did not want to stay long as he was attending Sunday School and did not want to miss it. This was a Sunday School of the Christian Science Church. I asked him what he did there but he did not want to tell me. At that time I was beginning to call myself an agnostic. I said I was not sure that God existed, and as John was a firm believer in Christian Science, he probably thought I would laugh at it, as I sometimes did about the more old-fashioned religious practices I had read about. For instance, I did not care very much about ornate religious vestments and still do not do so; and would say that I put up with them rather than like them, for the sake of the true message of the church. In Roman Catholic Churches of which I am a member to-day, the practice varies considerably from one church to another, in much the same way as it does in the Church of England.

In the same way the words of old-fashioned hymns made me curl up in horror. I did not want to sing about "the rich man in his castle and the poor man at his gate" as in "All things bright and beautiful", a popular school hymn,

I applauded one of the school-teachers when she said she did not like one of the hymns we had to sing at Assembly, because it was one of the Headmistress's favourites. "When you think about the words, you feel that it encourages too much dependency ", she said. "In to-days world you have to make your own decisions." This sort of criticism was about being too dependent on other people, people like our headmistress.

John, who had been staying with us for a short summer break in August, had to return home. His exams results were rather poor, so he had decided to leave school and take a job. He did not quite know what to do, so took a job in the Council Offices at Ipswich Town Hall. John wanted to be a farmer, or at least to work on a farm, and hoped he might have that opportunity later on. But his parents wanted him to to something better than start as an ordinary farm worker, after having been to Grammar School, and having obtained School Certificate, albeit that his results were not good enough to warrant him staying on to take the Higher School Certificate. I was disappointed that he was not staying any longer with us, and when I heard that he was taking a job, I said, "I suppose you won't be able to come and see us at Christmas.

John said, "I get one week holiday at Christmas, including the Bank Holidays. My job allows one day's holiday for every month I have worked, so I shall have completed four months work by Christmas and will be able to take four days holiday".

I did not think a week's holiday was very long, being used to school holidays which lasted at least a fortnight at Christmas, and sometimes nearly three weeks.

"Well, I am pleased you will be able to come. I am sorry you are not staying longer this summer."

At this time when Nana was dying. Her sister Kate was visiting almost every day. Aunt Kate noticed how fond I was of John and how I missed him when he went back so early to Ipswich that year. When John was gone, I managed to get some work pea-picking. I also tried picking up potatoes, but found it was too tiring. I never took any temporary work at the Apple Farm. My mother thought the work would be too tiring for me. It involved climbing ladders. When my mother went strawberry picking, I did not go with her as I was not able to to the bending down and work quickly. The pea-picking was much easier, as we tore the bines from the ground, and were able to hold them and strip them of peas while standing upright. I was able to work quickly and make ten shillings for a day's work, which greatly pleased me. I was looking forward to being able to buy twopenn'th of chips when I resumed school and had to wait about in the bus park in the early evenings.

Pea-picking usually only lasted one week; likewise the blackcurrant picking was usually over in each location within a week. Currant picking took place in July before the school term was over, and I had not been allowed any time off that year, so missed it.

Now that my father was coming home most week-ends from Colchester, we were settling down at Gordona as a family. When Nana's health finally deteriorated she moved into the little box-room where I used to sleep. It was small and easier to keep warm, and Nana had to take so many pain-killers that she spent most of her time asleep in bed. That conversation in the garden while she was peeling and cutting up the runner beans was the last one I remember having with her. The back bedroom with its double bed became my parents' bedroom. I had a bed large enough for two to myself in the front room, where I could look out and see Barrow field opposite my window. Downstairs we made the front room the "best" room, which we did not use except for special events, such as Christmas family get-togethers. We called the back room the living room, where we ate family meals.

I can remember that in London we only had one "living-room" but called it the "Drawing-room". Maybe it received that name because it contained a piano. But according to the Oxford Dictionary "Drawing-room" is definitely an upper-class word. It is defined as "Room for reception of company, to which ladies retire after dinner: levee, formal reception, especially at court". It becomes curiouser and curiouser to remember that we were talking about sitting or playing in the drawing-room, even at times when mum was wondering whether we would have enough money for bread and jam the following week!

This way of talking vanished when we lived at Gordona. Mum had probably brought these "posh" words with her from her years as a housemaid and receptionist for Sir Douglas and Lady Shields. We were definitely not "posh". I used to give an imitation of my Aunt Dorothy who used to say, "I never drink tea, because it spoils my complexion" in what I supposed to be a refined voice. I had forgotten all about Uncle Geoff and Aunt Dorothy as they never visited us while we at Gordona. I can't remember whether Uncle Geoff may have come once to see his mother before she died. The other brothers and sisters visited whenever it was possible. Aunt May came whenever she could get time off from her housemaid's duties with Lady Shields. Uncle Bill travelled from Beckenham, the southern suburb of London where he lived and worked and Aunt Kath, John's mother had only to travel from Ipswich, twelve miles away in Suffolk, so she came quite often. But my mother did all the work of looking after Nana, as well as entertaining visitors.

I was on holiday throughout August, so saw many relations. come again at Christmas. That summer John and I decided to make a rockery in the front flower-garden, which we had been left to look after without help from adults. We had cut the grass; had even got the heavy old-fashioned roller out of the disused garage, and rolled the lawn until it looked "perfect" according to John's standards. Now we starting looking round the back rough field for stones. Each stone had to be carried back in our arms as we had no wheel-barrow. Though we looked among the old deckchairs, discarded furniture and pots of paint in the garage, which we often called "the shed" we could not find any means of transporting the stones, not even an old dolls pram. So the stones were rather small. One larger rock we carried painfully by each holding one edge. The spaces between the stones were filled with earth and filled with plants. Some of these were removed from other parts of the garden. One was a creeper with small yellow flowers called stonecrop; there were also many houseleeks, an evergreen perennial which spreads rapidly; each circular whorl of green leaves grows tall in the autumn to produce a large pink daisy-like flower.

By the beginning of September in 1943, I was back at school in the Middle Fifth, and relations were no longer travelling to visit us. Only Aunt Kate, Nana's sister came almost every day. One sunlit day early in September I came home to find the doctor leaving the house . Aunt Kate was sitting at the table drinking tea.

"Nana died to-day," I was told. "Would you like to pull the curtains in the front room?"

I went into the front room and pulled the curtains, according to the custom which many people followed in those days. My mother came into the room and said that the funeral would take place next week. "Shall I go to the funeral?" I asked. "Can John come to the funeral?" John came over that week-end to express sympathy for Aunt Kate, Aunt Annie and for Aunt Gladys, my mother. But the older people decided that it would do no good for John and me to go to the funeral, so that on the day when it took place, I went to school as usual and John went to his work in Ipswich. John was sixteen and I was fifteen. I was not aware of who came to the funeral, but I don't think many people came back to the house afterwards. I don't remember seeing them."

I felt very sad, but because Nana had not been able to talk to us very much during the previous months, I did not miss her too much, especially as I went every week-end to see her sister, Aunt Kate,

Unfortunately there was an unpleasant incident just two or three weeks after Nana's death, which concentrated the minds of my mother and myself on our own predicament.

A KNOCK ON THE DOOR

One sunny September afternoon there came a knock on the front door.

Local people did not use the front door, and it was too late for the

postman.

I remained sitting at the table doing my first stint of homework and

wondering who it could be, while my mother went to the door. She came back

in tears, after having an argument and telling the two men to go away.

"We've bought the house," the men shouted. "You'll have to leave."

My mother explained that those two men said they had already bought the

house from my mother's eldest brother. They had told her that Mr Ruthen had

sold it in order to expand his business. By Mr Ruthen they meant Geoffrey

Ruthen, my mother's eldest brother.

"My own brother is doing this to me", my mother cried. "We wrote to

Geoff, as soon as Nana's funeral was over offering to pay rent of £1

week"

"Why did not he accept the rent?" I said.

"I have not had an answer to my letter. My mother has only been dead

for two weeks. How can he turn us out into the street? What shall we do?"

said my mother.

I had never heard of the word squatter, but I said, "I know what to do.

We'll just stay here. We'll lock all the doors if anybody comes and not

answer them. We'll just stay on; so they won't be able to turn us out."

I was quite sure this would work, as there was nobody else in the house

except my mother and myself with my father staying at week-ends. We knew

the voices of our friends and relations, like Aunt Kate or Maud and

Freddie, my grandmother's longstanding younger friends, and we were

friendly with the next-doors neighbours. On one side were Mr and Mrs Cole

with their daughter Pat, three years younger than me, attending the same

High School, and on the other side Mr and Mrs Roland with their son John,

attending the boy's Grammar School. I visited the Coles often for tea and

to play with Pat, and her severely mentally handicapped sister, who looked

like a five -year old even when she reached the age of 13. I thought these

people would support us, these neighbours and friends who had got used to

us living near them, and would not want to see us turned out into the

street by strangers.

"No, we must do something. We can't just stay here," said my mother, "

and do nothing about it".

We had been paying £1 per week for a similar sized house in London

and

considered it a fair rent, so my mother sat down straight away to write to

Uncle Geoff to ask him why he would not accept this rent, and as my mother

was his sister, and had looked after his mother, why he could not let us

stay. I posted the letter the same evening.

Next day my father arrived for our Saturday midday meal, usually corn

beef with potatoes and greens, and the first subject to be discussed was

the house. My father said that he did not believe that the house had

actually been sold.

"Those men were telling you that to frighten you," he said.

My mother agreed that this was probably true, for it seemed unlikely

that the house could be sold within two weeks of my grandmother's death.

"We will have to buy the house ourselves. I don't see any alternative,"

said my father. My mother got her Post Office book out. It contained

£200.

"I did not want to have to spend all my savings," said my mother, "but

I suppose I'll have to.

My father went out to telephone Uncle Geoff. We did not have a

telephone, but Uncle Geoff, as a businessman was sure to have one. In those

days ordinary people did not make phone calls, except for business

purposes, and then always from a public call box to business premises.

After an hour, he came back with the news that Geoff had not sold the

house, but wanted to sell it within a week. The price was £850, and

he

wanted the money immediately. We worked out that we could pay a £100

deposit and take out a mortgage for £750.

We had never heard of building societies, but a local builder called

Parsons offered mortgages to local people. My mother had seen his

advertisement in the local paper.

My parents went to see him that same week-end. What transpired was that

he would give us a mortgage. This meant getting £100 deposit

immediately,

and there was another blow. £50 was required for stamp duty, possibly

including some legal fees. That meant £150 from my mother's savings

was

needed. My father had no savings. He spent his meagre army pay in the NAAFI

as soon as he received each week. The mortgage involved paying £25 to

Parsons each quarter. £15 would be interest and £10 would be

payment off

the capital. We reckoned we could just afford it.

There was an atmosphere of excitement and tension in our house because

we had to withdraw the money by "Exchange Telegraph". Uncle Geoff would not

wait another two weeks for the normal postal withdrawal from the Post

Office Savings account to take place. My mother grumbled because the fee

for withdrawal by "Exchange Telegraph" was about £2. £2 was as

much as my

mother earned in a week! Life seemed desperately unfair and weighted

towards the convenience of the better off.

"I won't have much to do with Geoff once this is all over," said my

mother, and she could be blamed for that. Yet time would prove that though

buying the house was something we were forced to do to keep a roof over our

heads, it would be of great benefit to our family in the long term. Uncle

Geoff may have regretted that he sold it. I never saw him again, though in

later life he kept in touch with my mother's sister, Aunt May, who I saw

frequently.

A week later all our affairs were settled. My mother had only £50

left

in her Post Office account, but still had her job at the Apple Farm. With a

further £3 Army allowance, this was enough to pay all bills, but did

not

leave room for further personal saving.

Every quarter I went on my bike to Parson's house to pay the mortgage,

carefully calculated beforehand on a scrap of paper. It was set to decrease

as time went by, because we only paid interest on the unpaid capital.

Neither of my parents was earning enough to pay income tax. I think

Army pay may have been exempt, though I am not sure, but my mother's

£2

from the Apple Farm was below taxable income, and as a married woman she

was not eligible to pay a National Insurance stamp. The latter had its

disagreeable side, for it meant that she had to pay for doctor's visits.

Only men and single women in work were entitled to free consultations and

prescribed medicines had to be paid for. These were the days before the

introduction of the National Health Service. Unfortunately my mother was

subject to severe, unexpected attack of

asthma. When she could not

obtain

relief from her inhalant, she had to call out the doctor for an injection

of ephedrine. Nevertheless she continued work at the Apple Farm throughout

1944, taking her inhaler with her together with a sandwich each morning.

When the first mortgage payment became due, we had an agreeable

surprise. We found out that we were eligible for Mortgage Income Tax relief

even though we did not pay income tax. The £15 interest we paid

included

about a third income tax. So we only had to pay £10 interest in cash

quarterly. Parsons the builder explained this to us. So the house purchase

was costing us only £80 per year compared with £50 we would

have been

paying in rent. Not such a bad deal! In addition the rates had to be paid.

£2 per week was still a lot of money to be found from a small income

of not

more than £4.50 per week, and what would happen if my mother lost her

Apple

Farm job? These were the sort of worries which my mother carried.

|

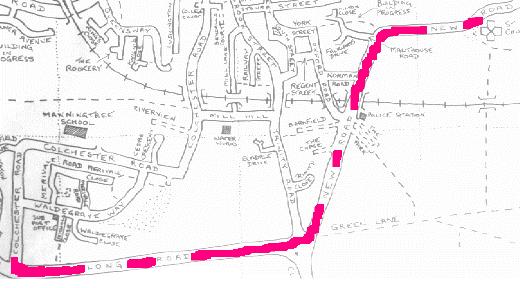

Note added by Andrew Roberts:

"Gordona", 162 Long Road, Lawford, Near Manningtree, Essex was purchased by Jack Martin from G. Ruthen, for £850, with a mortgage to (Mrs or Miss) E.H. Parsons between January and May 1944. (Solicitor's bill). The solicitor charged £25.17.6 of which £16.5.6 was professional charges and £9.12/- disbursements on stamps (required on the contracts) and stamp duty. |

Though I was fully informed about financial affairs especially the mortgage payments, I did not consider these things so deeply. I thought less about them than I had in pre-war London when life had seemed even more insecure. My thoughts were mainly occupied with hard study for School Certificate, and in addition I started to take an interest in Russia. A project on Russia was being done by the Middle Fifth.

In 1943 Russia was very popular because the Russian Army had consistently been driving the Germans back. Most of the large area which had been German-occupied Russia had been retaken by the Red Army. The Americans had also driven the Germans back in North Africa, but nothing had been done to free German-occupied Europe from the western side as yet, though the Allies had invaded Italy. The Russian Embassy had written to British Schools suggesting projects on the "Soviet Union" which could be undertaken by British schoolchildren, especially those in higher education. It was not suggested that we learn Russian. French and German were the only two languages commonly studied in schools, but the Russian Embassy suggested that British schoolchildren should write letters to Russian schoolchildren. The letters were to be sent to the Russian Embassy where they would be translated and sent to Russian schools. Eventually they promised that we would receive replies from Russian pen-friends. Miss Chapman who taught us French was in charge of this project. "It is a nice idea," she said, "though I would rather you had been able to have French pen-friends. Then you would have been able to write in French. It is a pity that France is still occupied but I expect by next year, you will each have a French pen-friend." We put a lot of effort into our letters. I described the commonplaces of life in Manningtree, not forgetting to mention that I was a collector for Mrs Churchill's Aid to Russia Fund. We handed them in hopefully.

The English teacher also had a project initiated by the Russian Embassy. Prizes of books were to be offered for the best three essays about the Soviet Union. These essays had to be from 850 to 1500 words in length. This was somewhat longer than a typical English essay. We did not usually write much more than 500 words, covering two or three sides of our. Two or small school exercise books. There were three titles, one of which was "What I would like to see and do in the Soviet Union."None of us knew much about the Soviet Union, so it was suggested that we get some books on the subject from the public library. Unfortunately, I could not avail myself of this option, as I had no access to Colchester Public Library. The girls who lived in Colchester had an advantage over the rest of us, as they were able to do some research in this library. Village dwellers had to rely on a travelling library which brought only about a hundred books to each village, and these were not changed for three months.

The only thing I could do was to list all the place-names in the sketch-maps in the newspapers of towns where fighting had been taking place. Names like Kharkov and Kiev. Then I tried to imagine what these places were like. Necessarily, my imagination was wide of the mark, and my essay received only an A minus-. I had found it very difficult to write as much as 850 words, whereas many of the library research had easily produced magnificent 1,500-word essays. I was not surprised that the highest mark which was A plus was received by Colchester girls. Sylvia who lived in Tiptree also received an A plus. I was not sure how she managed to get books on Russia to read, but she assured me that she had done so.

These essays were collected and posted to the Soviet Embassy and for the time being we forgot about Russia. It would be eight weeks before we received a reply. This would be after the Christmas holiday. As promised John came to stay for Christmas 1943. I noticed how much he had changed since he had started work, and was no longer a schoolboy. He did not seem to enjoy talking and walking with me as in former days. Aunt Kath came for a few days do stay with us. and brought the dog Gyp. I told my father how much I would like a dog.

John was due to go home shortly after Christmas. He told me did not like working at the Council Offices. He said he was going to apply for admittance to Agricultural College next September shortly after his seventeenth birthday. He did not think he would be visiting Lawford again. I said that I was sorry he was not coming again. I had got very good results in school exams, and John was quite jealous. He told me that the Agricultural College Course would be more advanced than the Higher School Certificate, and should lead to his getting a job as a farm manager. "John," I said, "I thought that you had to buy the land yourself, to be a farmer. I did not know they had farm managers." John said that he would never have the money to buy the land, at least not for many years to come, but maybe one day he would. I said that I thought it was something that ordinary people could not do, unless their parents had money, like becoming a doctor of medicine. "One has to have parents with money to pay for the course, if one wants to be a doctor I said, or a lawyer. Ordinary people can't do it. But I hope you manage to become a farm manager. I would like to study chemistry, and get a job in a laboratory, but I don't know whether I will be able to stay at school to do the Higher School Certificate." So I said good-bye to John that Christmas, and he did not come to stay at Lawford again, though Aunt Kath continued to visit, usually just for a day trip, to see my mother.

When I got back to school the results of the essay competition about Russia were received. Two of the girls who got prizes were Barbara from Colchester and Sylvia from Tiptree, who had been highly commended for their essays by the teacher. The third prize winner was Doreen, another Colchester girl. She had received the lowest marks of all from the teacher. "It proves that the teachers don't always make a good judgement", said Doreen. She had had access to Colchester Library for research about Russia. She supposed it was the content of her essay, not the literary merit which had won her a prize. These essays were not read out to the class, unlike some of our school efforts. The prizes from the Russian Embassy were a disappointment to the winners. They received three books each, all printed in the Russian language, and unintelligible to them.

We waited in vain to receive answers to our letters from Russian pen-friends. Miss Chapman, the languages teacher supposed they must had got lost, or possibly the staff at the Russian Embassy had had no time to do the translations. "Never mind the war is going well," she said, "and next year, I'm sure you will be able to write to some French pen-friends." It was early 1944 and as yet France was still wholly German-occupied. I was still interested in Russia so asked my Aunt May for a book on Russia for my 16th birthday in February. When it arrived I was disappointed to find that it was a novel about "Dasha", a child who lived in Tsarist Russia. "I am not interested in Tsarist Russia," I told my aunt. "I want to know what Russia is like to-day." "It is bad in Russia to-day," said my aunt, who was a royalist. "The good times were when the Tsar was alive." I said no more but inwardly disagreed. The book about the Russian schoolgirl was pleasant enough and good read, but it would not have helped me to write a better essay on "What I would like to see and do in the Soviet Union". While the war continued the Soviet Union continued to be popular with our schoolteachers, but they concluded that it was a waste of time writing any more letters to Russia.

Another new interest was a chance to do extra maths. I took a few lessons and had an introduction to differential calculus, which was normally done in the Sixth Form. We were also offered an opportunity to learn Greek, by our Latin teacher, if we missed the morning break. I did this for a few weeks, but soon got bored, as I considered that it was enough to study the subjects leading to outside examinations. We started doing old examination papers in mathematics for homework, and I was encouraged by getting an A plus for these almost every week.

FLYING BOMBS AND FRUSTRATIONS

Leonard came to stay for a Spring holiday in 1944. He was now fourteen. It was the first time I had seen him for four years. He had returned to London from his period of evacuation to a farm in Devon and was attending an Art School. His father had been a commercial artist and he wanted to follow this career. His mother had recovered her health, had a new council flat, and a well-paid job looking after an American Officer's club. She had to clean 30 bedrooms every day, but she said the men treated her very well and often left tips. "She fallen on her feet," said my father. "What about the bombing in London?" I asked Leonard. "It is quiet now," said Leonard. I imagined that the mass bombings of 1940 were still continuing; but Leonard said they had now abated. This was the quiet period between conventional bombing and the use of Hitler's secret weapon. There [were?] two quiet months in the summer term in 1944, but before we broke up for the summer holidays, air raid sirens were heard even at Colchester County High School for Girls.

In the hot July days of 1944, Middle Five A was in a relaxed mood. We had completed our most important exams of the year and had had the results. Almost everyone in the class was shown to be of School Certificate standard, so the teacher was allowing us to chat. But suddenly we heard a sound we had not heard for a very long time. The intermittent, strident note of an air raid siren. "You'll have to go to the shelter." There was some protest in the class, because we felt it was probably a false alarm. Everything was deathly quiet. Nevertheless, we trooped to the air raid shelter, which we had not used before. It was situated at the far end of the school playing fields. We were unused to its dimly lit interior.

However, I thought that it was absurd to get worried, because Colchester could not possibly have air raids such as I had experienced four years ago in London, which were always accompanied by a cacophony of sound, in which gun-fire, falling bombs, collapsing masonry and breaking glass were mixed. We strained our ears but continued to hear no external noise. I thought Marion was absurdly nervous when she started shivering, and saying that she was worried. Most of the girls were sitting quietly with our French teacher. Miss Chapman thought this a good opportunity to practice our French, so we given short sentences to translate orally into French. We sat for the space of an hour until the the continuous note of the All Clear sounded.

There had been no sounds either of gunfire, or of bombs. We had read about a new kind of flying bomb, one of which was supposed to have hit London recently, but had not taken it seriously. We did not discuss the war overmuch, considering that the tide was on the turn, and that it was only a matter of time, for all Europe to be free. What we may have discussed was our reduced rations. On the food front things were getting worse, not better. At least there was not yet any bread rationing. When we emerged from the shelter, we just laughed about the so-called air raid.

Just before the summer term ended I caught mumps. I did not know it was mumps until after the doctor had visited, while I was lying in bed with a high temperature and a most unpleasant sore throat. This was the only one of the less serious common childhood illnesses I had not yet had. I was sixteen years of age and thought "I am a bit old for mumps". I was relieved to hear that it was not too serious, and worried about the books I had left at school, because I had missed the last day of term. Usually we brought all our school books and personal possessions home before each long holiday. I had also left a few personal possessions including the artists' paints my father had given me four years ago, which were still very useful. None of the other girls had such good quality paints, so I prized them highly.

I had about ten days in bed and a further week resting downstairs. My mother was still working at the Apple Farm. She had invited my cousin Leonard to stay with us for the school holidays. He accepted; there was a chance for him to earn some money by doing temporary work at the Apple Farm. I found he was not very good company.

Aunt Kate found me one sunny day standing in the front garden, crying because my cousin John was no longer visiting. She remarked, "It is unrequited love". What do you mean, I said, "unrequited?" It was not a word I used.

This was my first long summer holiday during which I began to be bored. I had to do some work in the garden, and mowed the front and back lawns on my own. My cousin Leonard incarcerated himself in the unused garage during his spare time and practised drawing. When I asked him to help with the gardening, he said "This is my holiday". He wanted to pass his art exams. Having started the Art Course at 14 instead of 11, he had to catch up with the work. He was tired of outdoor work, having spent much time working on the farm at Devon, and at present doing daytime work at the Apple Farm. He praised my mother's apple pies. We ate apples in some form nearly every day. I became tired of apple pie. But as my mother worked at apple picking and had cheap supplies, they continued as our staple diet, something to fill up with after the meagre first course.

The meat ration had been reduced to about one shilling's worth per person per week. It was hardly enough to provide a week-end joint, even from rations for four. My father was provided with a ration coupon for his week-ends at home. Corn beef was not counted in the meat ration, but was itself rationed. We also had additional sources of protein in tinned food, which were also rationed according to the points system. In our house money remained short. There were two kinds of sardines. One sort cost fourpence halfpenny per tin and the best quality one shilling per tin. I remember protesting when I had been to the local shop, only five minutes walk away for our weekly groceries, and had brought back one of the shilling tins of sardines by mistake, instead of a fourpennyhalfpenny tin. "Take it back. We can't afford it", said my mother. I said that I was tired, but she insisted. So I had to go back to the shop, exchange the tin, and get our list of goods purchased amended. Our local shopkeeper allowed us to pay the bill at the end of each week, putting all goods purchased on a list. It appeared that every last piece of spare money was being extracted from my mother's income to pay the mortgage and the rates on the house. At that time there was also another tax on houses called Schedule A tax, but I don't think we had to pay this.

I was preparing to go to bed at 11 o'clock one August evening. My bedroom was lit by gas but I never used it. I usually undressed in the dark. Suddenly my room was illuminated as if by firelight, and I heard a sound like a mighty, rushing wind, as in a Biblical description. I thought, "They have come for me". I knew it was a flying bomb and prepared to be hit. Someone called me to go down to the cupboard under the stairs, but I thought there wasn't time, and dived under the bed. By that time it was all over. There had been a loud crash and then silence. I got up and joined my mother in the cupboard under the stairs. Leonard had been there but he came out and said he wanted to watch the flying bombs go by from the upstairs window, and take shelter if he heard an engine stop. That night we heard the rhythmic throbbing of the V1 flying bombs as they passed overhead. Most of them reached London. Those few which dropped in Essex were mistakes dropping before they reached their target because of engine failure. The intermittent note of their engines was easily recognisable. We used to listen, because we had been told that danger started if we heard the engine stop suddenly, instead of dying away in the distance. I heard several engines stop but no other bomb dropped so near Manningtree as on that occasion when I did not hear the engine at all, but only the hissing sound of a heavy hurtling object.

News soon reached the village that this flying bomb had dropped on a pair of cottages at Ardleigh, killing all the occupants of one cottage, two or three people only. Miraculously the family next door escaped serious injury, though their home was damaged, so as to be made uninhabitable. The cottages were by the side of the bus route to Colchester, four miles from us in Long Road Lawford. I saw them myself as I passed by on the school bus, when I resumed school after the summer holidays. Many Lawford people took the bus each morning to work in Colchester, so the incident was well-known, though not reported even in the local newspaper, which seemed to be confined to reports of births, marriages and deaths, and local church jumble sales, and was so boring that I hardly ever read it.

In this summer holiday, I did some pea picking, and also tried my hand at picking up potatoes, but could not keep up with the machine, so gave up this job after one morning. My cousin Leonard was far quicker than me at picking up potatoes. But in a task like currant-picking, which was the field work which I enjoyed the most, I could usually pick half as much again as either John or Leonard. Unfortunately all the currant picking was over before the school holidays, and the older girls were not allowed time off, as exams had to take priority.

During these summer holidays, I often visited Aunt Kate, leaving cousin Leonard ensconced in the garage busy with his drawing, if he was not working at the apple farm. One day when I entered her house, I found her in tears. "Ted has died," she said. She was inconsolable. " My Ted was the nicest husband you could wish for."

I said I was very sorry. She said that he had collapsed suddenly while working at the saw-mill, and had died two hours later in hospital in Colchester. Apparently he had had a heart attack. Uncle Ted was nearing seventy, about five years older than Aunt Kate. Like so many local manual workers, he had aimed to continue at work until he reached seventy. In those days the old age pension was very low, so all those in good health continued work past sixty-five. Aunt Kate told me that she had received a pension since sixty, because the wife was entitled to a pension at sixty if the man had reached sixty-five, even if he was still at work. This seemed complicated, and I did not fully understand it.

"The funeral is next week," said Aunt Kate. "I don't know how I shall manage now." She did not expect me to attend the funeral, but my mother and the relations in Ipswich would be attending.

This was a very sad day. Though I had lived in Aunt Kate's house for eight months, and used to play dominoes with Aunt Kate and Uncle Ted every evening, I felt I had never got to know Uncle Ted very well. He did not chat much, unlike the Aunts, who often gossiped about village life. Uncle Ted did not go out to public houses in the evenings but always stayed at home with Aunt Kate. He also did the gardening, providing beautiful lettuces and beans in the summer. I think he was too tired to talk much after all this work. The saw-mill was situated near the river, and sometimes I saw Uncle Ted at his work when I walked along the riverside. There were always a large number of men carrying strips of sawn wood on their shoulders and passers-by had to keep out of their way. They wore massive leather shoulder-pads on their working jackets. If I did see Uncle Ted I would wave and smile at him or say "hullo!" He was too out of breath to talk. I imagined that carrying the wood was all the men did all day. I never saw them sawing it up. I suppose they were taking it for transport by barge, but I never saw the barge. The front side of the factory adjoining the river bank was out of bounds to the public.

I went back home and told my mother about Uncle Ted's death. She was tired after a day at the Apple Farm. "It was a pity that he never lived to enjoy any retirement," she said. But it did not affect her so emotionally as her own mother's death. We did not know Uncle Ted very intimately. After a week or two Aunt Kate seemed to have recovered. She still had a full-time job looking after her sister Annie, and taking her out in the wheel-chair. She said she was in reduced circumstances and had to apply for National Assistance. This was what the addition to widow's pension for those unable to pay rents was called. She said she was so glad that she was able to get it. She did not grumble much. She was devoted to the parish church and spent much spare time making rag rugs to be sold at "Bring and Buy" sales to raise funds for this church. Its roof was badly in need of repair.

Before the end of this school holiday Aunt Kath visited with news about John. He had been accepted for a two year course at the Agricultural College. He had already gone away to live in rooms, as the college was situated somewhere in Northern England. Aunt Kath missed him. She invited me to spend a week with her in Ipswich. My mother was quite pleased for me to go, as I had been getting bored during this school holiday.