|

Survivors History archive of a discussion about Survivor History

that first appeared in Open Mind in

1998 and 1999.

(See place in history). Most of the text also appears on the

Mind website

at link one and

- link two

Reproduced with permission of Peter Beresford and John Hopton - Peter Linnett died 1.9.2007 |

| Open Mind May/June 1998 |

|

Past tensePeter Beresford on the need for a survivor-controlled museum of madness |

| Now is a crucial time in our history to reclaim our past. I am focusing here on two recent events which highlight the paramount importance of recording our side of the story before it becomes too late. The first is the announcement of the sudden death of community care. Since Frank Dobson's reported reversal of policy ('Care in the community is scrapped Daily Telegraph, 19 January 1998), confusion and uncertainty have surrounded future policy. Best guesses point to a reinforcement of failed medical solutions, without adequate financing, as the likely way forward. |

|

For service users, community care has been the most chequered and ambiguous

of policies. The efforts of individual survivors, survivor organisations,

allies and supportive practitioners have meant the winning of some genuine

gains in policy and provision. Rights, involvement and empowerment have

been forced onto the agenda. But, crucially for mental health service

users, community care has been a public relations disaster. Its inadequate

implementation and under-resourcing have set back by a generation both

public perceptions of madness and distress, and how many service users may

see themselves. The most appalling Victorian stereotypes of subhumanity,

dangerousness and axe-wielding murder have been reinforced with all the

power and subtlety of the modern media. It is probably difficult to

overestimate the destructive effects that this has, both for current mental

health service users and for anyone facing madness or mental distress for

the first time.

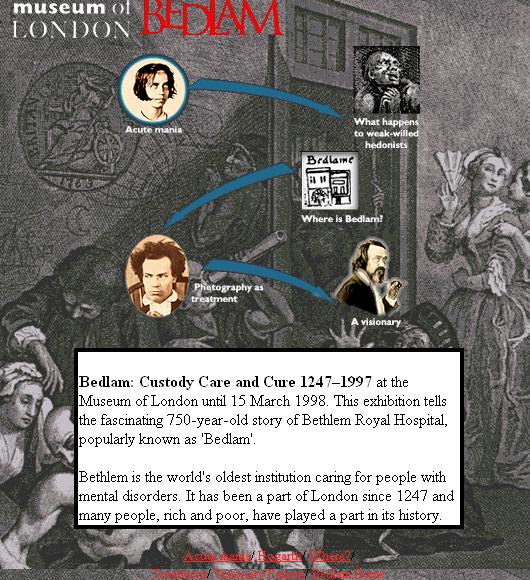

The rather more specific event which highlights the need for a user-created

history has been the celebration of the

750th anniversary of Bedlam. We

might have expected that a history that from its earliest days reveals a

familiar catalogue of inquiries, scandals, abuse and inhumanity would be

approached with the same sadness and solemnity as any other past inhumanity

or oppression. Instead it has become an opportunity, complete with

commemorative mug, keyring, paper clip and teeshirt, for reinforcing

professional pride and the brand identity of a medical product which by its

users accounts has more to correct than to be proud of. Perhaps most

disturbing of all has been its associated exhibition. This is presented in

classic modernist terms of centuries of progress, culminating in modern

psychiatry and the Maudsley Hospital.

It is made all the worse because it is given the respectability of being

housed in the Museum of London, which generally shows a sensitivity to

issues of difference and discrimination. The current psychiatric orthodoxy

that 'genes contribute to most mental illness' is presented as fact. The

experience of thousands of inmates is reduced to a handful of

indecipherable photographs posed in hospital wards and grounds, and select

biographies of the famous and curious few.

One of these institutions should be preserved as living testimony of the experience of the generations who lived and died within their walls. There have already been some attempts to create institutional museums, for example, at the Stanley Royd Hospital, the old 'West Yorkshire Pauper Lunatic Asylum' and at Calderstones Hospital. But what, crucially, should distinguish this initiative is that it is planned, established and run under the control of psychiatric system survivors and our organisations. Then the possibility of perpetuating professional accounts or becoming another peep show is minimised. It could also build on work that survivors have already done, putting together our accounts in exhibitions, books, news and broadcast media. Such a memorial could collect and house:

It could reflect the different periods in the history of psychiatry, from the insane asylums of the last century, to the chemical-based warehouse psychiatric hospitals of the second half of the twentieth century. It could make a strong case for lottery funding - unusual in being strong on heritage and 'user involvement'!

| Open Mind July/August 1998 |

|

From John Hopton

School of Social Work, University of Manchester As Peter Beresford points out, many existing 'historical' accounts of psychiatry and psychiatric institutions are problematic, based as much on assumptions and professional prejudices as on objective facts. On the other hand, there are some accounts by mental health professionals (such as David Clark's work on Fulbourn) which offer valuable insights into how and why mental health services have developed in particular ways. Thus, Peter Beresford's suggestion that the solution to this problem is for users to develop a competing historical narrative seems misguided. This would simply leave us with two opposing historical accounts with similar methodological flaws and biases. What is required is collaborative historical research, bringing together service users, mental health : professionals and 'neutral' historians : and social scientists. Then, the privileged knowledge of both mental ; health service users and professionals \ may be taken into consideration ; and the contribution which both : groups can make to our historical : understanding may be acknowledged |

From Peter Linnett - London SW17

Peter Beresford is right about 'the need for a survivor-controlled museum of madness'. Yesterday a friend and I toured a development of hundreds of expensive houses and flats on the former site of Tooting Bec psychiatric hospital. When it closed in 1995, the hospital had been there for almost 100 years. Many thousands of people had been patients there. We both used to work there, and wandering the site was a strange experience - not the slightest evidence of the hospital remained. The developer's glossy brochure did mention that this was the site of 'the famous Tooting Bee hospital'. It did not say what kind of hospital. At the very least, Lambeth Healthcare NHS Trust (former owners of the site) should have insisted on a memorial being placed there. The hospital was a grim place, but the people who lived, suffered and died there deserve to be remembered.

| Open Mind September/October 1998 |

Letters

museum of madness

In response to my article about a user-run museum John Hopton said it was misguided for users to develop a competing historical negative. As he must know, the issue is one of inequalities in power, and it is because of this that it is so important for survivors to be able to find a home for our history, just as other oppressed groups have done. As well as much media interest following the article, I have received many letters and enquiries from survivors interested in taking the idea forward. Following one suggestion received I plan to seek initial funding to take the idea forward. If you'd like to be involved please get in touch.

Peter Beresford

Open Services, Tempo House, 15 Falcon Rd,

London SW11 2PJ.

| Open Mind November/December 1999 |

Whose story is it anyway?

Do we need a survivor history of madness?

Peter Beresford and John Hopton develop the radically different views they first expressed in Openmind last year

Dear John

As you know I believe strongly that if we as mental health service users/survivors are to take control of our lives and future, then we must regain control of our past. We have to write our own histories. The history of madness, psychiatry and of us as individuals has so far been dominated and controlled by others; by professionals, charities, politicians and researchers. The effects have been demeaning and destructive for mental health service users. They have harmed the way individuals come to see themselves and how other people see them.

I know you don't share this view, but how can you justify this, given the appalling ways in which mental health service users/survivors have traditionally been presented and their worsening treatment in the media and political debate now? Current discussion is almost entirely preoccupied with service users as dangerous, murderous and threatening. Mental health service users have to change this.

Peter Beresford

Dear Peter

I've not always expressed my views about a user-centred history of mental

health services very clearly in the past, but I have no problem with the

idea of service users/survivors writing their own histories. Indeed, I

would be the first to concede that some terrible things have happened to

people in the name of mental health care and psychiatry. Furthermore some

of the histories of mental health services written by academics and mental

health professionals overlook abuses that have occurred. Worse still, some

of the accounts by mental health professionals are overly sentimental, and

almost make psychiatric hospitals sound as if they are desirable places to

be. In that sense, I think it's vital that service users develop their own

historical accounts. What I have a problem with is the idea of survivors'

histories being presented in one place and 'official' and 'academic'

histories being presented elsewhere.

John Hopton

Dear John

I thought for a moment we were in agreement! But your last comment makes

clear the gulf in understanding that survivors still have to bridge. You

seem to be standing by your original comment which triggered this

discussion that

"for service users to develop a competing historical

narrative seems misguided". The point is that it's not mental

health

service users/survivors who created the need to develop their own

histories, but the 'official' or psychiatric history that has excluded them

for so long. In reality, survivors' own views and accounts of their

experience and perceptions have mainly been ignored and devalued for

centuries. Their history has largely had to be a hidden and private one.

Meantime, psychiatry and its allies established their own powerful

organisations, colleges, journals and texts to perpetuate their versions of

history and of survivors.

History is always written by the winners, and mental health service users

have been cast in the role of losers. Now, as a movement of mental health

service users has developed, the official doors have opened a little. I am

all for collaboration, but this has really only happened because the

user/survivor movement has been able to exert influence and make its

presence felt. And, crucially, survivors have succeeded in getting their

voices heard, establishing their places to express their views and record

their personal and collective histories, where these could be developed on

their own terms, unedited and unqualified. This has led to new ways of

thinking and understanding about madness and distress; about psychiatric

categories like 'schizophrenia' and large-scale social issues like self-

harm and eating distress.

This is something to be proud of, not to regret. It means that there are

now different ways of understanding madness and 'mental illness' and of

addressing them. Writing its own history is one of the ways in which an

oppressed group can challenge what is done to it. All the movements:

women's, black people's, lesbians' and gay men's and disabled people's

movements, have done this. It's another sign of the collective progress

mental health service users/survivors are making.

Dear Peter

While user/survivor histories have indeed been ignored in official

histories of psychiatry and mental health services, I would suggest that

this reflects poor scholarship as much as it may reflect a deliberate

attempt to ignore their side of the story. Much of the history of

psychiatry and mental health services has been written by mental health

professionals who have no formal training in historical research.

Consequently, many such accounts have omissions, contain inaccuracies and

incorporate analysis based on false assumptions.

Such mistakes are easily made when people do not know where to find

appropriate archive material. Unless survivors/users developing historical

accounts are properly qualified historians themselves, or are able to

enlist the help of such people, they will inevitably make similar mistakes.

Indeed, I have read some accounts by survivors/users which are near-perfect

mirror images of some of the worst professional accounts. Whereas some

professional accounts tend to imply that all mental health professionals

are 'saints', some user accounts imply that all mental health professionals

are insensitive and uncaring. I have no wish to hide the fact that there

have been serious abuses committed in the name of mental health care, but I

also want acknowledgement that some professionals have made important

contributions to developing humanistic understandings of and responses to

mental health services. In that sense, it's not the development of

users'/survivors' historical perspectives which worries me. What does worry

me is that the development of separate historical narratives by

users/survivors will lead to a kind of propaganda war between the authors

of 'official histories' and the authors of the user/survivors histories.

This could result in each side selectively focusing on extreme but atypical

examples to score points off each other, so that we get further and further

away from a proper historical understanding of how we got to where we are

now.

What I would like to see is a single archive or museum where oral

testimonies from users/survivors would be side by side with oral

testimonies from mental health professionals, together with various

documentary sources and artifacts. If the testimonies of survivors/users

tell completely different stories from those of mental health

professionals, so be it. But I believe that we will never develop a truly

accurate history of mental health services unless mental health

professionals and survivors/users collaborate with properly qualified

historians.

John Hopton

Dear John

There's barely a word you've written I disagree with - in theory - but in

practice it doesn't work. History isn't neutral or just about expertise and

techniques. It's about who writes and controls it. It's about power,

inequalities of power and conflict. We mustn't deny this. The only

difference between now and the past is that conflicts between psychiatry

and service users are at last coming out into the open. A crucial first

step for us as survivors is to have safe space to develop our own

narratives and history (and survivors will tell of the good as well as the

bad), before our history can be placed next to professional accounts. We

also have much more to offer than 'personal testimony'. We have our own

important analyses and ideas. Yours is not an argument for rejecting

survivors' own history, but for ensuring survivors have more support to

develop it.

Peter Beresford

Dear Peter

My concerns are based on two considerations. Firstly, I have a somewhat

unfashionable belief in the quest for objective truths. Secondly, while I

agree that history is always tied up with issues of power and control,

critical writing on mental health generally (by academics, professionals

and survivors) can be a little one-sided. For example, while many abuses

have been committed in the name of behaviourism, many self-styled critical

thinkers who attack it fail to engage with B.F. Skinner's argument that the

form of behaviourism that he advocated was essentially humanistic.

John Hopton

Dear John

I can't agree with your last point, but what I think we have shown in this

correspondence is that with good will there can be collaboration and this

discussion can be taken forward. Here's hoping it now will be.

Peter Beresford

Andrew Roberts likes to hear from users:

B.F. Skinner is the psychologist most closely associated with behaviour

modification - the rewarding of desirable behaviour and ignoring of

undesirable. Behaviour modification has been attacked for being punitive

and manipulative. However, Skinner argued against the use of punishment,

and that behaviour modification was not manipulative because a client could

shape a therapist's behaviour as much as the therapist could shape theirs.

Andrew

Roberts home page

Andrew

Roberts home page

Top of

Page

Top of

Page

To contact him, please

use the Communication

Form