|

Judith ButlerHer ideas on the relationship between the human body and society, particularly in relation to traditional assumptions about genderLecture notes by Andrew Roberts

|

The ethical context

The moral of this story, as stated by Judith Butler in 1999, is this:

"What continues to concern me most is the following kinds of

questions: what will and will not constitute an intelligible life, and how

do presumptions about normative gender and sexuality determine in advance

what will qualify as the "human" and the "livable"? In other words, how do

normative gender presumptions work to delimit the very field of description

that we have for the human? What is the means by which we come to see this

delimiting power, and what are the means by which we transform

it?" (Butler, J. 1999

Preface)

"I pronounce you man and wife" says the priest

|

Normative gender is a term derived from

Butler's reading of Michel Foucault, it means gender as you are

required to be it, morally.

See the responses of Pope Benedict 16 and the Chief Rabbi of France, Gilles Bernheim and the Social Science Dictionary entry on marriage The purpose of this lecture is not to take sides in this ethical and theological debate, but to explore the relation between natural science (biology) philosophy and social theory in Judith Butler's work. Its focus is not religious determinism, but biological determinism.

|

Like Foucault, Judith Butler works by posing questions. I think those questions are useful ones, whatever answer one gives.

Work in historical context

24.2.1972

Judith Butler sixteen

years old. She later referred to

"my own tempestuous coming out at the age of 16" and spoke about

her experience, as a child and a young adult, of

"the violence of gender norms"

1984

Judith Butler's Ph.D

1986

"Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir's Second Sex"

1990

Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity

and

"Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and

Feminist Theory."

1993

Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of "Sex"

Summer 1994

"Interview with Josephine Butler" by

Peter Osborne and Lynne Segal: Radical Philosophy issue

67, Summer 1994, pages 32-39.

1997

"Further Reflections on the

Conversations of Our Time,"

21st century

Genetics and the sociology of identity [2013 Sociology]

1984

Judith Butler received her Ph.D. in philosophy from Yale

University. Her thesis was on the French reception of Hegel. A revised

version was

published in

1987 as

Subjects of Desire: Hegelian Reflections in

Twentieth-Century France

6.4.1975 Simone De Beauvoir

"Why I am a feminist"

"Butler ... reflects on the dualistic relationship between a

material embodiment of sex in chromosomes and genitals... and the socially

construed formation of gender identities."

|

Jesse Jackson stood as a potential Presidential candidate for the Democratic Party in 1984 and 1988. During the campaign Jackson began speaking of a "Rainbow Coalition" |

|

30.11.1984 North American release of Madonna's Material Girl.

"the boy with the cold hard cash Is always Mister Right, 'cause we are Living in a material world And I am a material girl" The European cover was more sexual, putting much more emphasis on Madonna's body and much less on wealth than the USA cover shown here. |

Amongst other things, the work of Judith Butler is a commentary on some of the work of Simone De Beauvoir. I will start by considering De Beauvoir and then consider Butler's commentary on the distinctions De Beauvoir makes.

But first of all, a bit of sexe French poetry from André Breton (1896-1966):

Polite meanings of sexe in French dictionary

Biology: whether a living being is male or female

By extension: the characteristics of men or women [but the word genre can also be used]

Collectively: men or women [the two sexes]

The sexual act

The other meaning of sexe in French:

sexual organ

|

So sexe is close to your body and can get sticky like old sweets,

whereas

genre, from which we get gender is ones manner. De bon genre: gentlemanly, ladylike. |

|

Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir's Second Sex

|

We will look at what De Beauvoir means in a moment, but let us look first

at some images of children.

Most images of children are created by adults. This one seems to suggest that what is under the nappy is a good indicator of the child's personality. Sigmund Freud said "human beings consist of men and women and ... this distinction is the most significant one that exists." He added that "Nature has determined woman's destiny through beauty, charm, and sweetness." (Click here for full quotation) |

|

According to Sigmund Freud, sexual life "starts with plain manifestations

soon after birth".

In 2002, Laura Leland explored what he meant in relation to her own beautiful baby. |

"Their genital development is similar, they explore their bodies with the same curiosity despite the differences. From the clitoris and penis they derive the same vague pleasure. "

" Already their sensitivity requires and object and they turn to the mother: the soft female flesh, smooth and elastic arouses sexual desire and these desires are prehensile: the girl like the boy kisses, feels, and caresses her mother in an aggressive way. They feel the same jealousy when a new baby is born, and they show it in the same way through anger, sulking and urinary problems, and they use the same coquetry to capture the love of adults. "

Simone De Beauvoir argues that we explore the world in different bodies,

but

the natural differences do not mean that our worlds are very different -

society builds difference around relatively insignificant biological

differences

Judith Butler does not dispute any of that, but she asks to what extent

our bodies are natural?

[Butler's commentary]

"If

'existing' one's gender means that one is tacitly accepting or

reworking cultural norms governing the interpretation of one's body, then

gender can also be a place in which the binary system restricting gender is

itself subverted."

"Simone de Beauvoir does not suggest the possibility of other genders

besides 'man' and 'woman', yet her insistence that these are historical

constructs which must in every case be appropriated by individuals suggests

that a binary gender system has no ontological necessity."

[We do not have to divide people into men and women]

"Simone de Beauvoir's ... strength of ... vision lies less in its appeal to

common sense than in the radical challenge she delivers to the cultural

status quo."

"To become a gender means both to submit to a cultural situation and to

create one ...

The body becomes a choice, a mode of enacting and reenacting received

gender norms which surface as so many styles of the flesh."

Outline of Butler's arguments developed from an August 2009 summary by

Malcolm Richardson

Judith Butler in 2008 |

Judith Butler is the author of

Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of

Identity

(1990), in which she argued against a

biologically determined

gender identity.

Judith Butler reinterprets Simone De Beauvoir's suggestion that "one is not born a woman, but, rather becomes one". De Beauvoir can be read as making a distinction between gender and sex in which gender is socially created around the natural body of sexual differences. Butler argues that "there is no recourse to a body that has not always already been interpreted by cultural meanings; hence, sex could not qualify as a pre discursive anatomical facticity. Indeed, sex, by definition, will be shown to have been gender all along". (Butler, 1990 p.8). |

Judith Butler uses some of Michel Foucault's ideas about the construction of self-identity to develop a performative theory of gender which argues that our sex is not something fixed and determinate, but something which is much more fluid and open. Butler develops the idea of Foucault, in a chapter called "docile bodies", that society inscribes on our bodies what we are.

The idea of perfomativity has a relationship to the idea of performance, but the emphasis is on the way discourses shape us rather than on our creatively acting a role.

Looked at from this more active perspective, Butler argues that gender is something we continually act out, or perform, in everyday life. It's analogous to a drag artist performing a male or female character. But it is more habit than creativity. Creative performance, however, is needed to subvert the perfomativity that we are given.

1990 "Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory." in Performing Feminisms: Feminist Critical Theory and Theatre

Performativity

and

performance

Perfomance and

perfomativity are related concepts, they are not the

same.

Let us start with the concept of performance that we all know, and

which is one of the key concepts of sociology.

|

"All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players: They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts". (William Shakespeare. As You Like It, Act 2, Scene 7, 1.36) The part an actor played on stage was once written on a separate roll of paper. From this, the part became known as a "role". From the idea that the whole social world is a stage on which the same people play different parts at different times, social scientists in the 20th century created "role theory". Talcot Parsons says we are actors in a social system. By clicking on this link you can read extracts from his work. Irving Goffman uses the "perspective... of the theatrical performance" to explain "everyday life". Dramaturgy is the art of making plays. Goffman says he is applying "dramaturgical principles" for his social theory. As a result, dramaturgy is (now) also in the Oxford Dictionary as a sociological theory which interprets individual behaviour as the dramatic projection of a chosen self". |

| Performativity | See performance |

"I pronounce you man and wife"

says the priest |

Language is performative if the saying of something does the deed. If the

authorised person says "I pronounce you man and wife" in the right

circumstances, the two people it is said to become man and wife. We say "I

would like to introduce you to..." when we are actually introducing people.

In social theory, Judith Butler calls for "...the understanding of performativity not as the act by which a subject brings into being what she/he names, but, rather, as that reiterative power of discourse to produce the phenomena that it regulates and constrains."

|

She appears to be saying that the discourses that we are part of produce

what we are.

|

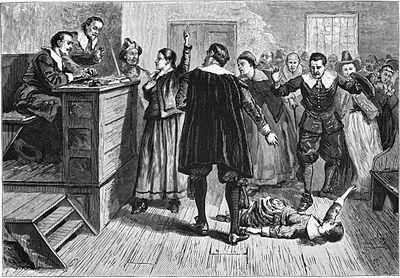

In a society that seriously discusses which people are witches

and which ones are not there will be people who identify and are identified

as witches.

Consider, for example, Salem in the 17th century. |

|

Such a society, however, would not not have beauty queens. |

"I pronounce you different bodies"

says society |

Language is performative if the saying of something does the deed. If the

authorised person says "I pronounce you man and wife" in the right

circumstances, the two people it is said to become man and wife

Performativity is a pronouncement of what we will perform. Society does the pronouncing Judith Butler asks:

"Is there a way to link the question of the materiality of the body to the performativity of gender? And how does the category of "sex" figure within such a relationship?"

|

|

Sometime between

1877

and

1893

the old nurse posed with her teenage charge

for a photograph by the new electric light

The teenagers name is Charlotte Mew, from which you can work out that you should say she and her. But Charlotte thought (outrageous child) that she could imagine and write as she liked, and so in her poetry she is sometimes him and sometimes her.

In more recent times, Crona is somewhat less sure how to cope with gender. |

Judit Butler was a board member and then ... board chair of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission from 1994 to 1997

an organisation that represents sexual minorities on a broad range of human rights issues.

"There I came to understand how the assertion of universality can be proleptic" [representing something future] "and performative, conjuring a reality that does not yet exist, and holding out the possibility for a convergence of cultural horizons that have not yet met."

Summer 1994 "Interview with Josephine Butler" by Peter Osborne and Lynne Segal: Radical Philosophy issue 67, Summer 1994, pages 32-39.

"certain bodies go to the

gynaecologist for certain kinds of examination and certain bodies do not"

"But ... Why is it

pregnancy by which that body gets defined?"

"the question of pregnancy ... is centering that whole institutional

practice here."

... although women's bodies generally speaking are

understood as capable of impregnation, ...

Her first-prize sentence appeared in "Further Reflections on the

Conversations of Our Time," in the scholarly journal Diacritics in

1997:

[This is about the move from relatively centralised conceptions of power

structures in society, which Butler associates with

Louis Althusser, to

decentralised conceptions of conflict rather than harmony, associated with

Althusser's student

Michel Foucault. She is saying that in the new Foucauldian view,

power is, at least in part, a struggle over the way we say

(articulate

and/or perform) things. If

we can alter the way we say or perform things, we can alter

society.]

21st century

Genetics and the sociology of

identity

Sociology, a journal of the British Sociological Association,

devoted a whole number to

Genetics and the Sociology of Identity

In relation to

genetics, the introduction uses Judith Butler as a key theorist

to negotiate

"the

tension between determinism and voluntarism in sociological

accounts of

identity formation" (p.876)

Voluntarism You decide who you are

Genetic Carried in your genes

Butler: a more sophisticated enquiry

Sociologists tend to stress social determinants of behaviour and

personality and/or voluntaristic ones, rather than body ones

If you want to see how one sided this sociological approach can become,

watch

"The Gender Equality Paradox" shown on Norwegian television

in March 2010. This was the first of a seven part series in which Harald

Eia confronted Norwegian social scientists with the evidence for some

biological influence on personality.

Judith Butler's theoretical work is valuable in devising a more

sophisticated sociological

approach to

genetics (and the body generally) because she acknowledges the

reality of

the body

[materiality] but argues that no aspect of it is free of

cultural

interpretation.

She says:

We have to examine the

dialogue of material and cultural reality:

The genetics issue of Sociology says:

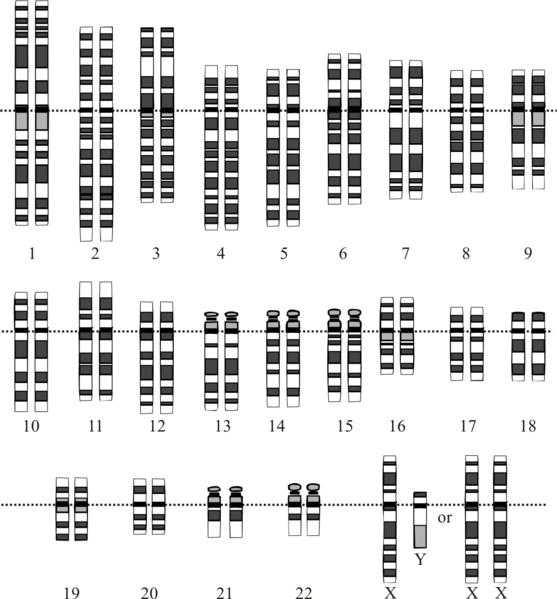

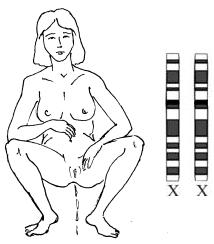

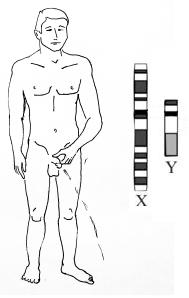

The drawings below are by

Steven K Ellis

. In most people the type of sex chromosome matches the type of

genitalia (sex organ). The genitalia are also called "primary sexual

characteristics". However, not everyone engages in sex and reproduction

whereas urinating is universal.

A diagram depicting the 23 human chromsomes. Based on a diagram in the

glossary of the National Human Genome Research Unit. It shows both the

female (XX) and male (XY) versions of the

23rd chromosome pair.

(Source Wikipedia)

Twenty two of the chromosomes in which the biological information is stored

to transmit to future generations have the same form in men and women. The

twenty-third is different. This then appears, on the surface, to be the

simple, biological, explanation for why men are not women.

The genetics issue of Sociology says:

BUT

First of all we need to recognise that biological determination is not that

straightforward. For example, there are people who for complex reasons are

given different sex identities to just "male" or "female".

The genetics issue of Sociology says:

Judith Butler suggests that looking at the way we think about people with

an anomalous biological sex can help us to understand more about how we

understand sex generally. She says

The genetics issue of Sociology says:

So reality is more complex than genetic determination. As well as the

influence of the body, we have to take into account the social stereotypes

that society imposes and the complexity of individual experience and

desires.

The genetics issue of Sociology says:

Andrew Roberts likes to hear from users:"and even if they could ideally, that is not necessarily the

salient feature of their bodies or even of their being women."

1998 Judith

Butler won first prize in the fourth Bad Writing Contest,

sponsored by the scholarly journal Philosophy and Literature. See

Press Release

"The move from a

structuralist account in which

capital is

understood to structure social relations in relatively

homologous ways to a

view of

hegemony

in which

power relations are subject to repetition,

convergence, and

rearticulation brought the question of

temporality into

the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of

Althusserian

theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in

which the insights into the

contingent possibility of structure inaugurate

a renewed conception of

hegemony

as bound up with the

contingent sites and

strategies of the

rearticulation of power."

October 2013:

Determinism Your genes decide who you are

In the 1930s the theory developed that the genetic information about what

characteristics are inherited are carried in an organic chemical which we

now call

DNA (Deoxyribose Nucleic

Acid). These acids are generally found only in the

chromosomes - Thread like structures in cells, see left.

Experiments in the 1940s and 1950s, using

micro-organisms, showed that DNA was the material that transmitted genetic

information.

"there is no recourse to a body that has not

always

already been interpreted by cultural meanings".

"Butler ... reflects on the dualistic relationship between a

material embodiment of sex in chromosomes and genitals... and the socially

construed formation of gender identities."

Genetically, biologists argue, we have our

biological sex (gender)

determined by the combination of X (female determining factor) and Y (male

determining factor)

chromosomes in our cells. Females have two X

chromosomes (XX) - Males have one of each (XY).

"The common understanding of genetics, and the social practices

in which it is employed, continue to be largely based on the assumption

that genes cause or are stable indicators for individual

characteristics."

"Bodies, genes, processes of brain development and aspects of

gender identity come in many irregular forms, including atypical genetic

variations in the sex chromosomes, which occur in 1 out of 700 live births,

as well as the many other ways in which bodies and desires trouble the

hetero-normative ideal of sex and gender identity"

Spanish hurdler

Maria Patino considered herself a woman, as did everyone else.

Standard sports tests said the same in 1983 but then in 1985 the tests said

that she was a man.

Read what

Judith Butler wrote about genetics in 1990

"The point here is not to seek recourse to the exceptions, the

bizarre, in order merely to relativize the claims made in behalf of normal

sexual life. ... it is the exception, the strange, that gives us the clue

to how

the mundane and taken-for-granted world of sexual meanings is

constituted."

"the complexity of individual experience and desires does not

fit with stereotypical identities. Individuals are forced to match imposed

(or seemingly imposed) societal expectations."

"Recent developments in genomic science and its interpretation

appear to favour following Butler... genetic research has highlighted the

extent to which ordinary bodily development is shaped and defined by social

as much as genetic and other biological factors. Scientists and clinicians

are nowadays much more inclined to assume that physiology, sexual desire

and gender identity, far from being naturally linked or aligned with one

another, are profoundly shaped by cultural idioms and individual

experiences."

See Subject index on

biological bases of behaviour. Gina Rippon's

articles on "neurononsense" make for interesting reading.

To contact him, please

use the Communication

Form

Headings

Butler's commentary: the body politic

Judith Butler's actual question

International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission