Cosy Corners in Depression and War

Autobiography of

Joan Hughes

The story of one person's nests

Summers in the Country 1935-1939

COUNTRY: GORDONA, LAWFORD, NEAR MANNINGTREE, ESSEX

Recently, I visited

the graveyard in Lawford, next to

Mistley Church,

where

some

of my

deceased relations

are buried. On an old head stone, I

read that William Malyn Ruthen died on 30th March 1937, aged 77. He was my

grandfather on my mother's side. Unlike my father's father who I do not

remember, I have some recollections of him. Every summer for six weeks, I

stayed with my grandparents in Lawford, starting probably in

1935, when I

was about seven and old enough to be left with them.

|

Their house was called "Gordona". Lawford was very peaceful. Opposite Gordona was a field, in which alternately, wheat, oats or barley was grown. I think I was my granddad's favourite grandchild, the only girl apart from Maura, who was four years younger and not old enough to stay with them.

My mother said, "They would be too tired to have the house full of children, and always found Uncle Geoff's children tiring, but they delighted to have me stay with them. Wearing a blue and white checked summer dress and a green cardigan, I had a photograph taken with them in the front garden among the roses, which I have unfortunately lost.

|

Lawford Iron Works at Manningtree may have been founded around

1830. In

1841 the Bendall names connected to the foundry were David Bendall (30),

Hannah Bendall (born Coddenham, Suffolk 1812) and Offwood Bendall (born

1814).

In 1839/1840 David Bendall is recorded in a London Trade Directory as

"ironfounder and agricultural implement maker", Lawford, Essex, David

Bendall died in Tendring in the late summer of 1843.

Offwood Bendall had been

baptised in Kettleburgh, Suffolk on 9.10.1814. Father: Duffield Offwood

Bendall. Mother: Lydia Seaman. Hannah Bendall (his sister?) married Philip

Johnson Harris, a local grocer who became (or also) a farmer, in 1842 and

died in the late summer of 1883. In 1855, under iron-founders, a London

trade Directory has O.Bendall, Lawford Hill, Manningtree. The firm made

Bendall

ploughs, water carts, land rollers and hoop hoes.

Lawford Road had parts north and south of the Turnpike Road from Manningtree (1851). Offwood and Mary Bendall, and family, are at "Lawford Hill Iron Foundry" at the "End of Lawford Street" on the north side of the Turnpike Road. William and Mary Ruthen are on the south part, near the "end of Lawford Street". Mary A. Ruthen a domestic servant working for James (the miller) and Sarah May at Mill House, also south of the Turnpike Road. Joan's great-grandfather, also William Ruthen, but born Orford, Suffolk about 1823, worked as an "Iron Furnace Tender" in 1881 (aged 60), when William Malyn (aged 21) was a "moulder". Great-grandfather William appears to have worked at the foundry since before 1851. He died (aged 63) in the spring of 1884. William Malyn Ruthen born July 1860 in Lawford, Essex. Parents' home Lawford Street. Moved to Brook Street, Manningtree by 1891. Next door to George J.P. Nevill (his future father in-law). Also in Brook Street 1901 (after marriage). In 1911 the inhabitants of the two neighbouring houses were: William Malyn Ruthen 51 Moulder Iron - Agnes Ruthen 39 - Agnes May Ruthen 12 - Geoffrey Frances George Ruthen 10 - Rose Kathleen Ruthen 8 - William Arthur Nevill Ruthen 6 - Stanley Lawrence Ruthen 4. Next door: George James Palmer Nevill 67 Widowed Maltster Labourer - Francis Henry Nevill Son 36 Single Maltster Labourer - Annie Nevill Daughter 28 Single Housekeeper - Gwendoline Chapman Cousin 12 school born Mill Hill, Middlesex - Gladys Mary Ruthen Granddaughter (Joan's mother) 13 at school. Offwood Bendall and Son, Lawford iron works, Agricultural Implement Makers, Engineers and Iron Founders in Essex Trade Directory for 1908. Joshua Robert Markwell Fitch, born 1879, bought the firm in 1913 and managed it until his death on 16.12.1946. He was the patentee of a "furrow spreader of improved design". See Grace's Guide. |

My grandfather had retired when I knew him. But most men in those days worked until the age of 70 if they were fit. My grandfather had worked at a small iron foundry, the only sizable factory in Manningtree.

| Frederick C. Wilson born 16.5.1905. Extruding machinist. Plastics and his wife Maud L. Wilson born 24.9.1909 lived in Milton Road in 1939. |

In later times most men were employed at the plastics factory in Brantham, and this is where "Uncle Fred" worked. Maud and Fred lived in Milton Road, a small turning off Long Road, which in those days ended in a small field, left rough, but containing a large run where hens were kept behind wire netting. Pigs were also kept, but could not so easily be seen behind stone walls. Uncle Fred was reputed to be "dim". I could not understand why. When not too tired, he entertained children with cardboard cutouts of funny people who moved their arms and legs when the string was pulled. Fred had to endure the system of piecework at the plastics factory. It was reputed to be the toughest and most unfair system in the country. Before the war there was no union. In latter days, Margaret Roberts, who was later to become Prime Minister Thatcher worked in the research laboratory attached to it. But that was after the war. Conditions improved then. Uncle Fred was able to work there until retirement, but about 1979, this factory closed, shortly after its former employee had become Prime Minister. Maud and Fred were friends of my grandparents, but about forty years younger.

[Bob] Their youngest son spent a lot of time at Gordona. Apparently, his wife Edna was ill; they split up, Edna living with her parents and Bob, whose real name was Stanley Lawrence staying at home. He was a taciturn chap, spent most of the fine weather in the garden, in which he did a good job; but indoors he held a newspaper in front of his face most of the time, and rarely spoke. This uncle worked s a compositor in a printing firm in Colchester. Later in life, he was employed as a reader, reading the first proofs of books produced by his firm, looking for printing errors. His wife Edna rallied sufficiently to take on the running of a small shop, near the beginning of the war and Bob moved out.

|

In 1939 only Agnes Ruthen

and Stanley L. Ruthen were living at Gordona. Edna was at Countisbury,

Station Road, [Wrabness] Tendring, Essex, with her father Harry Cottee, a

fencing works manager born 16.2.1874, mother Elizabeth H Cottee born

2.8.1871, Noel Cottee, born 25.12.1914 who was a skilled labourer

(armaments) and Jean P Cottee born 24.3.1929, who was at school. Bob was

living at Gordona in the

autumn of 1940.

Edna May Ruthen of The Cash Stores Wrabness Essex (wife of Stanley Lawrence Ruthen) died 25.9.1944 at East Suffolk and Ipswich Hospital, Ipswich. Probate 2.1.1945 to Harry Cottee timber merchant and Elizabeth Harriet Cotte (wife of the said Harry Cottee). Effects £515.3s.4d. She was 33 and her death was registered in Ipswich. Bob remarried in 1948 to Olive G. Bloomfield (born 1927 Blything Suffolk?). Their son Robert B. Ruthen was born in the summer of 1949. Uncle Bob died in 1977. |

|

Nana Ruthen and her family

Joan's grandfather, William Malyn Ruthen, married Agnes Nevill (born 26.7.1871) in 1896. She was the daughter of George James Palmer Nevill (born Lawford August/September 1843), a local Grocer's Assistant who became a Maltsters Labourer, and Sarah Ann, (born Osborn, Lawford, about March 1845). Her older sisters were Elizabeth (born Manningtree about 1867, entered domestic service) and Esther Lavina (born 1869. Married James Cooper a Norwich factory worker. Died Norwich in the summer of 1933), and her younger sisters and brothers were Francis Henry (1875-1924), Arthur (born about 1877), Selina Kate (Aunt Kate who married Ted) and Annie (who Joan lived with in 1939), and Rose, E. (born about 1886). In 1891, before she married, Agnes worked as a nurse in a private boarding school in Hornsey, North London. The Lawford and Manningtree field below Mistley churchyard Nana died in September 1943 and was buried with her husband. Uncle Ted joined her in March 1945, Annie in the late summer of 1946, Joan's mother in September 1948 (Grave L21 Manningtree), Aunt Kate in September 1966, Joan's father in October 1985 and Joan in December 2008. Family connections December 2008 By the time Joan died, her main family connections were her cousin Leonard Noble and his family on her father's side. On her mother's side she kept in contact with John and Sylvia Beeson in Clacton, and knew about their son Richard (in Africa) and two grandsons. Apart from this, she had the addresses of her cousins Jill and Peter Ruthen.

|

My grandmother, who I referred to as "New Nana" until 1936, when my other grandmother died, always wore black, after Granddad had died. White was allowed as a trimming, but absolutely no colours. People over sixty or so, usually wore dark colours in those days, but I noticed the difference between her clothes and those of my great aunt Kate, ten years younger. Brown was her usual colour. But in wartime, when she also lost her husband, Uncle Ted, mourning was not worn. There were clothing coupons to be considered, besides the expense; if anything my great-aunt was poorer than my grandmother. Ted worked carrying wood at the saw-mill, still open in war-time, long after "the foundry" had closed down.

Most of my days in the country were spent taking walks with the great-aunts, playing with my cousin John in fields nearby, or cutting the lawn and weeding the garden, together with John usually.

The month of August was spent leisurely in this manner, a most welcome break from London streets, and eagerly looked forward to every year. Most people would say I was far too eager to leave home. "Didn't I miss my mother?" they said, when for four weeks each August , I left for the country.

The first occasion must have been 1935, because I remember meeting my Granddad. I was only seven years old. I was photographed with him, but all these photos were lost in the 1939 war.

|

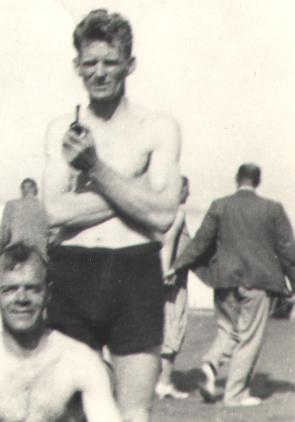

Granddad and

Nana Ruthen at the centre, in the front.

Geoffrey and

Gladys Mary (Joan's mother) behind them. Gordona belonged to

Uncle Geoff.

On the left: the nurse like uniform suggests Agnes May (Aunt May) , with Rose Kathleen Aunt Betty (Cousin John's mother) behind her. [Great] Aunt Kate lived nearby. On the right: William Arthur Nevill (Uncle Bill) at the back, with Stanley Lawrence (Uncle Bob)) sitting in front of him. |

But I have one group photo of my mother's family, taken before I was born. This was rescued from the house Gordona. Nana and Granddad are there, with their six grown-up children. Gladys Mary, the oldest was my mother. Then came Geoffrey, the tallest of the boys. Then Agnes May and Rose Kathleen. All the girls were short women. My aunts were known to me as Aunt May and Aunt Kath. Kath was also known as Aunt Betty Then William (Uncle Bill), finally Stanley Lawrence (known as Uncle Bob). Those best known to me were Aunt May, Auntie Betty and Uncle Bob, the latter because he lived at Gordona for a time.

|

Joan's mother, Gladys Mary Ruthen (1897-1948), was the eldest daughter of

William Malyn Ruthen (born 1860, died 30.3.1937) and Agnes Nevill

(26.7.1871-1943), who were married in 1896. She was born in Manningtree,

Essex.

on 21.6.1897. Her sister, Agnes May Ruthen (1898-1977 - Joan's Aunt May)

was born 18.12.1898. Geoffrey Frances George Ruthen (1900-1976) was born

10.11.1900. The next child was Rose Kathleen Ruthen (1902-1981 - Joan's

Aunt Kath or Aunt Betty). Followed

by William Arthur Nevill Ruthen (1904-1974 - Joan's Uncle Bill), Finally

Stanley Lawrence Ruthen (1906-1977 Joan's Uncle Bob), born 13.9.1906.

|

What I liked about the country was the fact that there was a field opposite the house; and even better than this field from the point of view of a London child, was the small rough field just two minutes walk away, behind our back garden. The wild flowers delighted me, much more than my grandmother's cottage garden flowers. There was not a patch of accessible rough ground in West Kensington; so these rough fields were a voyage of discovery, each day discovering a species of wild flower I had not seen before. Mauve flowers like yarrow and blue speedwell were my favourites. Barrow field opposite the house grew oats , wheat and barley in successive years, and I soon learned to tell the difference and tasted the grains. The seeds of wheat, nutty and crunchy were the only ones I continued to eat; the others proved too dry.

The train journey from Liverpool Street in London to Manningtree Station took two hours in those days. Sometimes I was accompanied by Aunt May, when she took a week's holiday from "service", and would stay one week with her mother, then would leave me on my own for three more weeks.

Gordona was lit by gas-light. This needed a match and great care when lighting, otherwise the flimsy gas-mantles would break. I could not turn on the switch as I did with electric light in London; I was not allowed to light the gas, so used a candlestick to bed, and read many books by this poor light, oblivious to the eye-strain this incurred. The mid-Victorian books belonging to Nana were fascinating because different from London library fare. Mostly they were about children overcoming horrible circumstances because of their religious faith. For instance, Liz's Shepherd was about a young girl who played with clothes-pegs as a substitute for dolls, then died young in her poverty-stricken home, sustained by a belief in "Her Divine Shepherd". I considered it a fantasy on the same level as "Grimm's Fairy Tales"!

Another tale called "Steadfast and True" was about Huguenot children fleeing from persecuting Catholics in France. This had a happy ending and was one of my favourites, in spite of the fact that I was a Catholic, albeit an ignorant one.

In contrast, there was an adult book belonging to Uncle Bob called "Dracula" by Bram Stoker, but being told that it was about a monster, I was too terrified to read it. I had read "Grimm's Fairy Tales" in London and they were bad enough for me. I preferred Enid Blyton, until I discovered the "William" books by Richmal Crompton in Fulham children's library and these became my firm favourites. However in Lawford I read "Old St. Paul's" from Nana's bookshelf, which was terrifying but realistic; not a horror tale, but a serious historical novel. It was about the great plague of London.

In the box-room where I often slept in my grandmother's house was a framed text on the wall, the Beatitudes, which unconsciously, I learnt by heart, because I read it over and over again until darkness fell, when bored in bed with nothing else to read. I said my prayers most nights, but was not terribly religious and did not enjoy going to church with my grandmother. I had not had enough religious instruction to understand what the service was about, so found it boring.

| Joan's cousin John Beeson from Ipswich is the son of Aunt Betty and Uncle Fred Beeson. Aunt Betty (Rose Kathleen Ruthen) is sometimes called Aunt Kath, but calling her Aunt Betty distinguishes her clearly from [Great] Aunt Kate. |

As it was August when I visited Lawford, and I can only remember hot days, most of my time was spent out of doors. My cousin John, Aunt Kath's son, living in Ipswich often arrived by bicycle. He lived in Ipswich, over the Suffolk border and about ten miles away. From the age of eleven this journey was quite easy for him. Probably I first met him when he was 9 and myself 8. To begin we played in the rough field just over the back garden fence, finding wild flowers and other delights. John, living in a small town and more in touch with country life, was able to tell me their names. From this field we exited into Milton Road, a short cul-de-sac ending in a larger rough field. Often we walked straight by the chicken-coops and pig-sty through the rough tall grass which was about as tall as we were to reach the hedgerow at the back. There were many blackberries, but also some thornless hollow bushes . One of these in particular was our "hideout". One day we saw a lizard beneath this bush. It shed its tail and scampered off. The nerve in this tail kept it active. We watched the dance of the lizard's tail,,entranced for a whole hour.

But one day I was walking alone on a footpath through an adjacent cornfield and came across a large green coiled snake. I fled home terrified, worrying that it was a poisonous adder.

"Its only a grass -snake", I was told by one of the adults in the house at the time. "Adders are very small".

In nature-study, I had learnt about the three snakes which could be found in England, and theoretically knew about their markings, but on seeing a real snake I could remember nothing and anyway did not want to stop to look closely. I don't think I ever saw another snake thereabouts.

What John and I waited for in vain on many occasions was the sight of a rabbit. By local lore, it was reputed that the rabbits huddled in the middle of a cornfield when it was being cut. In those days the tractor went round the outside of the filed, doing up the corn in bundles as it was cut. The square or oblong of uncut corn got smaller and smaller, until there was only a small strip left in the centre. John and I watched Barrow field being cut each August, and we were armed with stones. We were told that it was allowable to kill the rabbits by stoning them, and take them home for dinner! This may have been a tall story but I believed it, though I never saw a rabbit I watched faithfully each year when Barrow Field was harvested.

After the harvest came the Harvest Festival. This was the one Church Service which I enjoyed, spending the time gazing at the ears of corn and prize specimens of marrows and many other locally grown vegetables which were exhibited in Manningtree Church at this time. We also visited the local flower show, run by the Women's Institute, loved the colourful display from local gardens. There were also entries of "wild flowers". These quickly drooped when picked and put in water, we noticed, which discouraged us from picking them.

When we were slightly older, John and I were encouraged to mow the lawns and cut the edges of the grass with shears at Gordona. This was a complicated job as there was a circular rose-bed in the front garden, as well as one curved and one straight long border. Using the shears was a tedious job, which I found tolerable because of John's company. When we had finished the front garden, we would then mow the small lawn at the back of the house. We aimed at perfection, and John would never leave the work until it was fully complete.

The summers of 1935 to 1939 all seemed hot and endless. I enjoyed being on holiday with Nana more and more each succeeding year and delighted in the company of cousin John. But in 1939 I was disappointed when I was only allowed one week. I believe this was because the house was fully occupied by Uncle Geoff's family, but I did not understand why this was the case. It was probably because they considered in too dangerous to stay in their usual holiday home at Dymchurch on the South Coast. So most of August 1939 I was cooped up in London, playing with Leonard in the new Anderson air-raid shelter.

OUTINGS

Outings were the high spots of my pre-war life, when we could afford

them, because my parents finances fluctuated wildly. In some periods, my

mother was frantically worrying how to buy food for the week, and other

times, she enjoyed a Saturday evening visit to the public house. Often I

accompanied my parents, so they did not stay long in the pub. The visit was

often the climax to a walk on Barnes Common, where we flew a kite, and the

three of us all behaved as if we were children, wandering happily among the

gorse bushes. Those were quiet times. There were millions unemployed in the

1930s, but the impression I got was that either these people despaired

silently, or otherwise they organised marches and meetings, somewhat away

from ordinary street life. I did not see any violent folk, except outside

pubs at closing times. There was a Saturday afternoon closing time, when

occasionally I would see two men fighting, and was wise enough to walk on

the other side of the street.

But on Barnes Common , all was peaceful, and we relaxed. After the

afternoon walk, I was given a glass of fizzy lemonade, to drink slowly

while my parents went into the nearby pub. It may have been dark, and I may

have felt a little chilly, but the pub. lemonade was something special, and

made up for everything. Lemonade has never tasted so good, anywhere else,

or at any other time.

Another regular Saturday outing was a visit to the Natural History

Museum or the Science Museum at South Kensington. Dad would take me to

these places on his own, while my mother may have gone out with a woman

friend. In the Natural History Museum there was a square balcony with

stuffed animals, still there to-day, but now a minor feature amidst the

expanded exhibition with its videos, and pictorial displays.

But in those days the stuffed animals was all there was. My father

would pause outside each glass case, and talk to me about the animal

displayed. We would read the labels gravely. It would take a full hour or

two to walk round the display, to which most people would allocate only ten

minutes today. The museum was sparsely attended in those days, and mostly

by local families; South Kensington could be reached easily on the District

line from West Kensington, and there were no museum entrance fees, so it

was a cheap outing for the less well-off. Dad was more interested in

science than art, so we omitted the Victoria and Albert Museum.

But the Science Museum was next door, and would be the subject of a

separate Saturday outing. We did not do too much on any one occasion. There

was a children's room in the basement, with numerous buttons to press,

which set the exhibits in motion. Of most interest was the act of walking

through one exhibit and setting off an alarm bell.

"You have broken an invisible ray," my father said.

I did not understand what was happening, but I wanted to find out, and

thought that one day I would. It aroused my interest in science.

In the main part of the museum,there was also an exhibit of pure

chemical elements, as many as could be conveniently assembled. The coloured

elements attracted my interest, for example, sulphur as a heap of yellow

crystals. Incidentally, the first time I handled sulphur myself was not in

a laboratory, but as a powder to rub through my dog's coat, when he had a

skin infection. The dog did not arrive until 1945, when we living in the

country, in Essex.

My father preferred the mechanical exhibits. I was quite content to

accompany him through the adult museum and look at everything.

The museums were for ordinary Saturday afternoons. But just after

Christmas, in the cold of January, my parents took me regularly to a

variety show, at the Granville Theatre. This was situated at the end of

North End Road, beyond the market stalls. It has long since closed down.

It was an old-fashioned variety show with about twenty separate acts.

There were jugglers, trapeze artists, giants and dwarfs doing acrobatics, ,

clowns and comics. Much of this sort of entertainment would be considered

undignified today and would not take place, but it was common fare in those

days. However, we never went to a circus, so I did not see any acts with

animals.

My

Aunt May

frowned on circuses. She had a high respect for animals,

and told me that it was very cruel to make them perform tricks. Sometimes I

went on outings with my mother and Aunt May, while my father was at work,

or doing other things.

The regular afternoon outing was a picnic in Kensington Gardens with my

mother and Aunt May, on her afternoon off from her job as a maid with

Dr and Lady Shields. From her very small wage, she would buy

strawberries, and

we would eat them seated on the grass. Then we would look at the Round

Pond, at Peter Pan's Statue, and sometimes would walk over to the Albert

Memorial in Hyde Park. I would ascend the many steps and examine the

carvings, although Aunt May pronounced it "a hideous structure".

I was interested in the park-keeper's cottage, and said that it was the

house I would most like to live in. Aunt May did not think much of that

idea.

"It is lonely, and the man is tied down to his job all the time

there," she said. " You would not like it".

Sometimes I sailed a small boat on the Round Pond. Occasionally my

father came on a week-end trip to Kensington Gardens with my mother and I,

but he was not very fond of this park. One day the small boat was becalmed

in the middle of the pond, and I wondered what to do. But eventually the

boats all ended up on the far side of the pond, and we simply walked round

there to re-claim then. Kensington Gardens with Aunt May was the type of

outing I most looked forward to, when it was in the offing, and was always

disappointed, when for some reason Aunt May could not come.

Vaguely I remember going to a pantomime with Aunt May and my mother in

wintertime. I did not like it as much as the Granville Variety theatre.

Trips further afield were very rare. One day in the middle of the week,

in summer time my mother took me for a day trip to Broadstairs. She sat in

a deck chair in the sun, while I played with a bucket and spade.

"It is too hot", I said. " Lets move into the shade". I did not like

too much sunshine.

"I like sitting in the sun", said Mother , but she agreed to move.

We moved off to a secluded bay where there were no other people. She

sat down and went almost to sleep while I paddled. We were in the middle of

a curved bay, and everything seemed peaceful.

But the tide had approached leaving only a few feet of sand. Suddenly

my mother became alarmed. The tide had approached the cliffs on both sides,

cutting us off.

"We'll have to go now and hurry," said Mother.

We had to paddle through the water, and it frightened me, in case it

should become too deep before we reached the corner.

"Just hurry up and don't look down. We will do it, " said Mother and I

took her hand, following behind her.

I think the water was up to my knees before we reached dry land, round

the corner of the bay, where there were steps up to the top of the cliff.We

were very relieved after our narrow escape.This was the only day trip to

the seaside I had with my mother on our own.

We had only one other day trip as a family to the sea-side. On this

occasion we went to Sheerness. It must have been very dull, as I don't

remember much about it. My parents grumbled about delays on the train, and

when we reached the shore, they said "Well, there is not much at

Sheerness." I have never visited this place again.

Weeks would go by without any outings. These were the greyer times,

when Dad spent all Saturday afternoon in the pub, and came home drunk. We

had three ornamental swords hanging as a decoration in the hall. On one

particularly frightening afternoon, two of my father's drinking companions

grabbed these and started to fight in the street. Apparently they did not

hurt each other and this may have been a mock fight, but none the less

alarming. "He has such changes of mood," said my mother, referring to my

father when we were alone. "Sometimes things look so black, but sometimes

he is nice as pie".

Once a year maybe, I went to London Zoo, with a larger family group.

Aunt Violet and Leonard and my family usually went together and this was

another of the high-spots of the year. The elephants were my favourite

animal, but I liked to watch them from a distance. In those days the

elephants paraded round the paths with a howdah on top, and children were

given rides. A ladder was needed. "It is too high up," I said and refused a

ride. I think Leonard was more adventurous and had a ride. After the

elephants, I most liked to see aquatic animals, such as sea-lions and

penguins. There was no chimpanzee's tea-party in those days. We were

content to see the animals behave as naturally as possible, but I fear, all

too often, they were confined in cages too small for this. I refused to

enter the reptile house. Snakes terrified me.

I never went to the zoo since 1939, until just recently. In 1992, the

most recent news is that London Zoo may close owing to lack of enough

visitors. Attitudes towards keeping large animals in cages have changed, so

there are mixed feelings about preserving the Zoo. Polar bears are no

longer there; it is impossible to provide enough space for such animals to

enable them to behave naturally. This argument may apply to other large

animals, though the present staff of keepers are very fond of the animals

and treat them very well. Recently, I went to the Zoo for the first time

since 1939 "to say good-bye to the animals". There are no elephants rides

today, though the elephants are still there and are regularly exercised. I

found one of the keepers in the cage with a lemur playing with it, because

it was lonely. She told me that three of the keepers had been accepted by

the lemur as its "lemur family". This was done because this animal had been

rejected by its mother and had no natural lemur family.

In 1939, I was accepting the delights of the zoo uncritically.

I must not forget the Boat Race. As far as I can remember, Cambridge

was almost always the winner in the mid and late 1930s. I did not care who

was the winner and did not care very much about the Boat Race. I used to

accompany my parents to the nearest point on the towpath where we could

watch the boats go by. This was near Hammersmith Bridge. There were usually

a lot of folk milling about on the towpath. It was a pleasant walk, and we

took lemonade and sandwiches. But watching two boats go by was not

exciting. We never knew until much later who had run the race. Our position

on the bank had none of the excitement of the finishing post, nor any of

the fanfare of the starting point. Leonard told me that he used to watch

the boat race, quite unaccompanied, as his mother was not interested in it,

but she allowed him to walk out on his own from the age of seven or eight.

Leonard never came with us.

However when my father visited the public house at Brompton, he usually

took Leonard with him. I used to go too, while my mother stayed at home.

This public house was quite a long walk away, near Brompton cemetery, and

we were tired when we arrived. It was usually daylight, on a Saturday

afternoon. On these occasions, my father was well-behaved, and not in the

mood for getting drunk. We went to Brompton principally for the walk, and

when he took us with him, he did not go to a public house where his male

drinking companions congregated. He was primarily a social drinker, so when

he got drunk, it was usually under the influence of like-minded companions.

My mother used to worry, because I believe he wasted his week's wages on

buying rounds of drinks; not so much on drinks for himself. It was the

waste of money which worried my mother, rather than a bout of occasional

drunkenness, which soon passed. But when he went with family, it was a

matter of one or two drinks only, a glass of delicious pub. lemonade for

Leonard and myself, standing outside in the sunshine, and afterwards a walk

round Brompton cemetery to look at the graves. He would sometimes give us

the benefit of his scientific theories, and Leonard told me that he said

"The graves are gradually sinking, and will one day fall into the sea". He

must have been thinking in terms of geological ages, but Leonard did not

appreciate that, and teased him.

|

Geoffrey [Francis George]

Ruthen, born 10.11.1900.

Enlisted in the Army

10.11.1918. terminated because of illness. Previously worked as a

hairdresser for Filley and Barrow, 26 High Street, Beckenham, Kent.

Geoffrey married Dorothy Kathleen Couchman (Aunt Dorothy) in Tendring in the late summer of 1926. Dorothy was the daughter of Charlotte Emily (born Charlotte Murrell in 1881) and William David Couchman (born in Hawkhurst, Kent, 1883) who married at St Pauls Church, Deptford, Kent on 8.4.1903. William David Couchman was a British soldier (Royal Artillery) based in England and Ireland from 10.11.1893 to 22.11.1915. Dorothy was born in Belturbet, County Cavan, Ireland on 14.12.1903. She was the oldest of several children. She died 25.4.1984 in Bromley, Kent. Their three children are William Geoffrey Ruthen, born summer 1927 in Bromley (still living recently). Moira Ruthen, born 23.5.1931 in Croydon who died, aged 10, in the late summer of 1941 in Watford, Hertfordshire, and Michael Francis Ruthen, born 31.5.1932 in Bromley. Geoffrey Ruthen, ladies hairdresser, 97 High Street, Beckenham, Kent in 1934 Trade Directory. In 1939 they lived at 95 High Street, Beckenham, Kent. He was a Master Hairdresser and also an ARP Sector Warden. Irene M. Ironside lived with the family as a domestic servant. Joan's immediate family had little contact with Geoffrey and his family after the death of Nana Ruthen in September 1943. (See Buying Gordona). This was war-time, but Geoffrey was expanding his business. He maintained contact with Aunt May, and Joan heard about his family through her. Geoffrey Ruthen of 6 Jevington Close, Cooden, Sussex, died 30.12.1976. Estate £5,056. Death registered in Bromley. His solicitors, Wood and sons. 18 High Street, Beckenham. Currently there is a firm Ruthen and Perkins, Hairdressers, at 98 Bromley Road, Beckenham, Kent. |

During my holiday I met these cousins, but was most glad when they were not there, as they were very noisy. The nursemaid seemed quite unable to control the boisterous behaviour of the two boys, one a year older than me and one a year younger. Maura, the youngest daughter was the only one of the family I was able to make friends with. Tragically she died of meningitis when she was about eight years old, just before the second world war.

The cousin I became most friendly with was my cousin John who often stayed and occasionally brought his dog Gyp.

|

|

|