Conflict

Finally we look at Durkheim's explanations of conflict in modern

society.

Durkheim, as we have seen, argues that solidarity, in its two inter-related

forms (mechanical and organic) is the basis of human society. In simplified

terms, co-operation not conflict is where we all start.

But this does not mean that competition, conflict and deviance are

unnatural in society.

Durkheim argues that it

"

is neither necessary nor even possible for social life to be without

conflicts. The role of solidarity is not to suppress competition, but to

moderate it."

Elsewhere he argues that certain forms of conflict are not only natural,

but essential to the healthy operation and development of society.

However, he identifies abnormal form of the division of labour,

which, in

the examples we will look at, are forms that interfere with society's

healthy

way of resolving problems. Durkheim speaks of "abnormal forms where the

division of labour does not

produce solidarity"

(see Durkheim). It is here that he finds the explanation for

"industrial crises" - "antagonism of labour and capital" - and "class-

war"

Durkheim maintained that the interaction between individuals and groups in

society spontaneously generates

rules (sometimes called

norms) that guide our conduct. Without such rules we are

lost about

what to do, and so we naturally negotiate what the rules should be. Such

negotiations may include competition and conflict over the rules. This is

not abnormal. The abnormality is when something prevents the

negotiation or re-negotiation of the rules. What could do this?

For our purposes, we can identify three things that can interfere with the

spontaneous negotiation of norms (rules):

1) insufficient contact for negotiation

2) the speed of social change

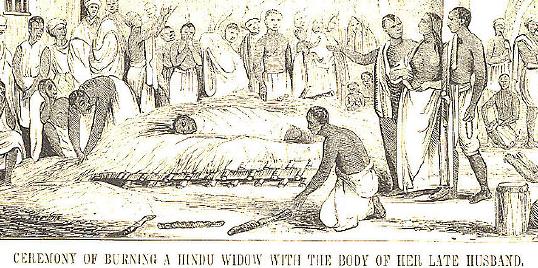

3) forced hierarchical relations

The

anomic division of labour

Insufficient contact for negotiation is the

important element in what Durkheim calls the

anomic division of labour - That is a division of labour outside

of social rules or norms.

An example he gives is when the development of the market in what we

now call

"globalisation" outstrips the ability of public institutions to

regulate it. The harm consequent on the anti-social operation of an

unregulated market is exacerbated by the speed of social change. Durkheim

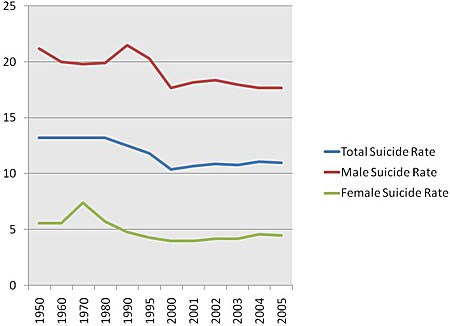

also identifies the speed of change in economic crises in a later book as

responsible

for

"anomic suicide".

In the long-run, such disorders rectify

themselves. However, time does not restore the disequilibrium that results

from

"the still very great inequality of the external conditions of the

struggle" which is maintained by the

forced division of labour.

Time Line

Time Line

Social Science Dictionary

Social Science Dictionary

Durkheim and Weber's contrasting imaginations

Durkheim and Weber's contrasting imaginations

Andrew Roberts' home page

Andrew Roberts' home page

Society and Science home page

Society and Science home page

Durkheim extracts

Durkheim extracts  Weber extracts

Weber extracts  Spencer extracts

Spencer extracts

Richardson and Roberts on Bauman and May

Richardson and Roberts on Bauman and May