A

history of Social

Science

from ancient Greece to the 21st century

Introduction

Reason in Plato and Aristotle and how it relates to gender

Hobbes and State of Nature Theory

Filmer and Locke

Rousseau and the French Revolution

Adam Smith

Jeremy Bentham and Utilitarianism

Robert Owen

Theory in the 1830s and 1840s

Utilitarianism, Owenism, Thompson and Wheeler and feminism

Poor Law and Social Policy

Lord Ashley and Mill and Taylor in 1848

Marx and Engels in 1848

Engels "Origin"

Durkheim and Weber

Freud

My name is Andrew Roberts and I give the lectures on Social Science

History. Most of you who take it will not start

with much knowledge about history or the people we are talking about -

Weblinks from the online lecture notes will let you find out what you need

to know, when you need it.

These are the online lecture notes. The lectures use a lot of pictures. You

need to take the images stimulated in your mind by these, and use them

to help you read.

The web lecture notes began as just the notes used in lectures, and

some of them are still just headings. I have, however, been adding

pictures, writing the notes out and building in links to the web versions

of the texts referred to.

The central issue of the first module in this course is the development of

a "scientific" approach to

themes previously the concern of theology and philosophy. We look at how

"science" develops from

"theology" and "philosophy".

You should ask yourself the questions:

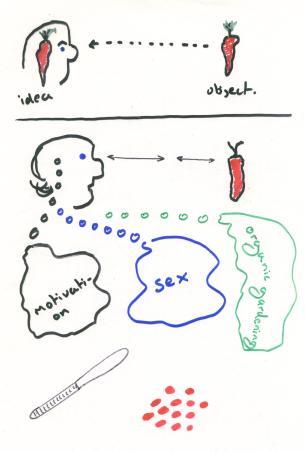

I will start by suggesting that science requires at least two elements:

ideas and observations.

Often, when people talk about

science, they talk mainly about the observations side. We, however,

will look at the ideas side of science.

Introduction to Social Science History

You will not find statistics

or other social data in these lectures - We are looking at the thinking

that comes before the statistics.

|

|

What has pink elephant to say about this?

What has pink elephant to say about this?

|

|

Reason is something which lets you get results from your mind, without consulting books or asking a lecturer. Theory, reason and an argument all allow you to anticipate the direction they are going in. |

|---|

|

For example. High on a Scottish mountain you meet someone who needs to travel to Room B2 on Enfield Campus at Middlesex University. It is your campus and your university - but you have never seen B2. You have seen B4. Do you say "I cannot help you", or does your mind anticipate where B2 is? The way you anticipate involves using a theory of numbers. You think B2 is likely to be near B4, but why?

|

August Comte (1797-1857) divided the history of ideas into three stages:

- theological,

- philosophical (critical)

- scientific (positive)

| theological |

Filmer

|

|---|---|

| philosophical |

Hobbes and Locke

|

| scientific |

Adam Smith Utilitarian Theory,

|

We can begin the story of modern social theory with the "state of nature" theories of Hobbes and Locke and the theological theories of Filmer.

You all know what a state of nature is: It is walking about in the woods with no clothes on!

|

click on the serpent to read his story |

The Adam and Eve picture illustrates theological and state of nature

theories which you can read about in

chapter two of Social Science

History. The same page has these two descriptions:

"state of nature theorists"...

work out what society and

politics are about by imagining ..human beings..stripped of ..social

characteristics .. They ..try to show how the needs of those individuals

explain their need for society and politics...

Theological theories say that there is a body of divine law from which you deduce natural law.

Hobbes wrote: Leviathan.

Leviathan is a monster

described in Job, one of the

oldest (?) books of the Jewish

Bible. There are two monsters described in this passage of Job:

Leviathan

and Behemoth.

This is a picture of them drawn by the artist-poet William Blake

Views differ about what they are, but

Leviathan sounds to me like a

crocodile, and

Behemoth like a hippopotamus. Hobbes named another of his

books Behemoth

Views differ about what they are, but

Leviathan sounds to me like a

crocodile, and

Behemoth like a hippopotamus. Hobbes named another of his

books Behemoth

By clicking on the links above you can read the descriptions from Job. Particularly notice these parts from Leviathan

His scales are his pride,

shut up together as with a close seal.One is so near to another, that no air can come between them.

The arrow cannot make him flee:

slingstones are turned with him into stubble.Darts are counted as stubble:

he laugheth at the shaking of a spear.

"Upon earth there is not his like,

who is made without fear.He beholdeth all high things:

he is a king over all the children of pride."

Hobbes' book has the full title Leviathan Or The Matter, Form and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil

We can take the word "Commonwealth" as meaning " Society". The book, therefore, is about the matter, form and power of society. It was published in 1651, just after the English Civil War.

Although we have classified Hobbes as a philosopher, he thought of himself as a scientist. Hobbes wanted to make a scientific model of politics like Galileo's model of the Universe.

Galileo's theories started from simple

axioms,

or basic statements,

about the laws governing matter. One of these laws is what we know call the

law of inertia, that a body continues its motion in a straight line until

something intervenes to stop it.

Hobbes wanted a scientific model of the political universe. He

argued that science should use theories based on "right reason". Thes

would be modelled on the mathematical disciple called

geometry. (If you click on the coloured

word

it will take you to the Study Guide page about geometry).

Hobbes says that if we give correct definitions to things we can argue from those definitions to universal conclusions. Correct definitions are like axioms. Hobbes calls them definitions because he is an empiricist.

Hobbes is an Empiricist: He believes that all our ideas come from observations:

Observations set up trains (chains) of thought:

Some just meander:

Some have an end:

In a state of nature other people are either:

- an end or a means to an end:

- People about whom one fantasizes their utilisation for obtaining

desires.

or - an obstacle stopping us getting our end

- People about whom one fantasizes their death.

Here are some suggestions:

We are looking at how "science" develops from "theology" and

"philosophy".

Science involves both ideas and observations: We are looking at the ideas

side of science. Ideas come in patterns that we call theories.

The two types of

theories we are looking at are:

"State of Nature" and "Theological"

The three theorists we are looking at are: Sir Robert Filmer, Thomas

Hobbes and John Locke, all of whom lived in the 17th century, at about the

time of the

English Civil War.

Today I am going to look at the way that their different theories

explain

power

Power is a general concept. If you have a theory of power

that explains politics, the same theory should be able to explain the power

between men and women, or the power of parents over children.

I will start with Hobbes, because he can be summarised by the picture at

the front of his book.

Go back and look at Hobbes: The Big

Picture.

Hobbes: The Big

Picture

At the front of Leviathan there is a picture in which the ideas of the book

are summed up. Before, you read further, click on the coloured words above

to look at some of the main features of the picture. Scroll down to the two

columns of small pictures at the bottom. What are the pictures off? What do

you think they symbolise?

People can think what they like (nobody can stop them), but

they cannot read or speak anything that the sovereign does not permit

because that would endanger the peace.

I will use the crown for the King's power

I will use the crown for the King's power

The bench can symbolise Parliament's power

The bench can symbolise Parliament's power

If you click on King Adam you can read what

Rousseau thought of Filmer's arguments

If you click on King Adam you can read what

Rousseau thought of Filmer's arguments

Click coloured words to go where you

want

Click coloured words to go where you

want