|

by Andrew Roberts

Histories are

bedtime stories - No nightmares please. I like my stories to have a happy

ending, but this one just goes on and on.

|

Different stories

Questioning histories

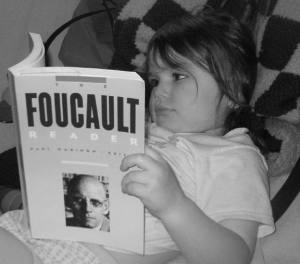

Do you think about Foucault

as someone who asks questions, or as someone who provides

answers?.

Here, I consider him as asking questions

about the

histories of

(stories about) psychiatry,

criminology and sex.

He tells different stories to question the

first stories without completely replacing them.

|

Foucault appears to recognise some truth in the story of psychiatry and

criminology as movements towards greater

humanity, and in the story that sexual expressions were repressed and then

liberated. But he invites us to consider important questions about how

these stories may distort the truth.

When we have understood the stories he criticises, the questions he asks,

and the new stories he suggests, we cannot rest. Foucault's search for

truth is in the questioning, but the answers lead to more questions.

Foucault says:

"... do you imagine that I would take so much trouble and so

much pleasure in writing ... if I were not preparing ... a labyrinth into

which ... I can move my discourse, opening up underground passages, forcing

it to go far from itself. ..."

Patterns of power and concepts of self

Foucault's work explores patterns of

power within a society, and how power relates

to

the self.

Foucault's approach is usually historical,

attempting to show that

everyday ideas about reality, like

reason and

madness,

punishment, and

sex

change in the course

of history.

History is not simply about the past for Foucault, it

penetrates our everyday lives.

Foucault created new concepts for understanding

many things as

power relations, including not only prisons and the police,

but also the

care of the mentally ill and welfare. When he turned his attention to

explaining power and sex, he challenged the adequacy of the main concepts

of power that we have and suggested others.

Looking back on his work, in a

May 1982 interview, Foucault said that he had been

exploring the

relation between reason, knowledge, truth and power. His

thesis might be

stated as knowledge gives power, although it is not the same

as power.

Born

15.10.1926 in Poitiers

History penetrates Foucault's childhood

"Chancellor Dollfuss was assassinated by the

Nazis in...

1934.

The New York Times 26.7.1934

|

It is something very far from us now. Very few people remember the murder

of Dollfuss. I remember very well that I was very scared by that. I think

it was my first strong fright about death.

I also remember refugees from Spain arriving in Poitiers. I remember

fighting in school with my classmates about the Ethiopian war.

I think that boys and girls of this generation had their childhood formed

by these great historical events. The menace of war was our background, our

framework of existence.

We did not know when I was

ten or eleven years old, whether we would become

German or remain French. We did not know whether we would die or not in the

bombing, and so on."

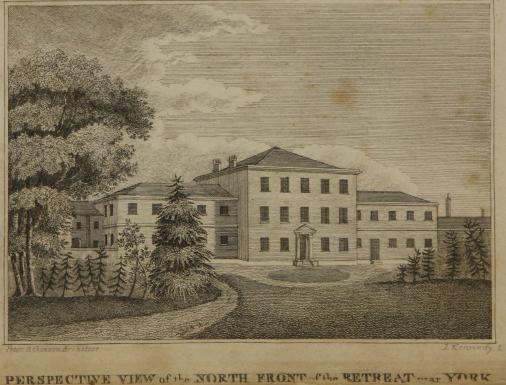

We could regard Madness and Civilisation as Foucault's contrast and

comparison of the modern 19th century lunatic asylum (beginning with the

Tuke's Retreat) with what had gone before and

Discipline and Punish as Foucault's contrast and

comparison of the modern 19th century prison (beginning with

Bentham's

Panopticon idea) with what had gone before

Foucault on one (reform) version of history

"We know the images. They are familiar in all histories of psychiatry,

where their function is to illustrate that happy age when madness was

finally recognised and treated according to a truth to which we had long

remained blind"

"Thee has had many wonderful children of thy brain dear

William, but this one is surely like to be an idiot"

Esther Tuke to her pig-headed husband who wanted to build

a refuge for lunatic Quakers

Tuke's history of Tuke

|

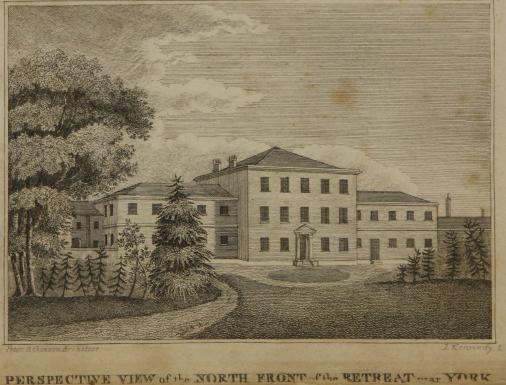

The Retreat, near York in England, was first opened in 1796, by

William Tuke and his son, co

founder Henry Tuke. The Tukes were originally tea and coffee merchants, who

were born into and practised

Quaker discipline and principles. As a result

of the death of a former mentally ill friend, who died within the

York

Asylum, they decided to establish a hospital of their own, built

on

humanitarian principles.

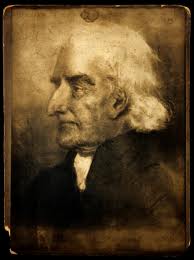

Samuel Tuke continued the work of his grandfather,

William, in managing the Retreat.

|

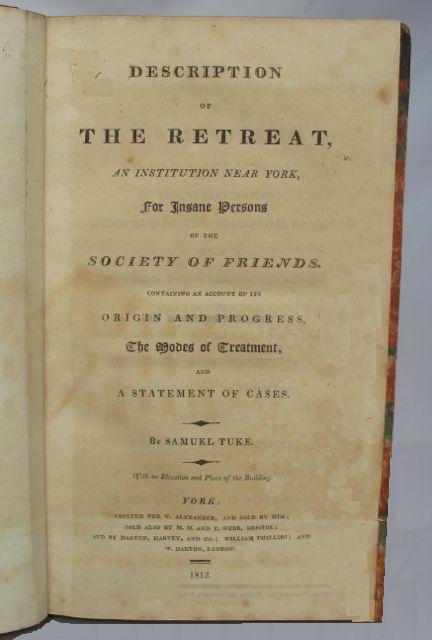

The Description of the Retreat was written in 1813 by Samuel Tuke,

and

focuses on the humanitarian care of the insane within the York Retreat.

The Description of the Retreat outlines a new approach to insanity;

one

which was based on the idea that reason exists within the insane

individual. It is perverted rather than absent.

The Description of the Retreat provided a model (ideal) for asylums

during the period of

therapeutic

optimism

A

Bethlem bleeding cup from the collection of Dennis Leigh

(Leigh, D. 1961, p. 80)

|

The orthodox treatment of insanity in the eighteenth century included using

mechanical restraints to control patients and medical treatments such as

purging and bleeding. The Retreat attempted to replace both mechanical

restraint and medical treatment with what was called moral management.

|

The chapter on

Medical Treatment says that it is to be used a little as

possible in the Retreat. When

it is practised, it must be done with a degree of moderation and carried

out by only the most experienced of superintendents.

"Medicine, as yet, possesses very inadequate means to relieve the most

grievous of human diseases." (Tuke, S. 1813, p.111)"... "But the remedy, in

such cases ought to be applied with great judgement: and its application

should always be witnessed by the master or mistress of the family." (Tuke,

S. 1813, p114).

Later, non-

Quakers applied this idea to large asylums. See, for example,

Harriet Martineau's description

of the Hanwell Lunatic Asylum in June 1834

In the chapter

Moral Management, it is proposed that this is the

best and most appropriate approach to dealing with those of diseased minds.

Moral Management was a system of treating insanity by the institutional

regime of the asylum, rather than by medicines or physical treatments.

"Whatever theory we maintain in regard to the remote causes of insanity, we

must consider moral treatment, or management, of very high importance."...

"Much may be done towards the cure and alleviation of insanity, by

judicious modes of management, and moral treatment." (Tuke, S. 1813, p131-

2).

Tuke argues that if the right type of establishment is created, and with

the correct exercising of moral guidelines then the patient could adopt a

'healthy mind'. Tuke thought that fear and a natural desire for self esteem

were elements which existed within those who were regarded as insane, and

proposed that manipulating these in the desired way could lead the patient

into developing 'self restraint' and 'self control' over their state of

mind.

Moral treatment is not just effective through a specific type of treatment

but also exists within the layout and structure of the Retreat. The Retreat

is designed in a way that allows the mad man to know he is being watched

and that bad behaviour will be recognised. Moral management was not only

embedded within the psychological treatment of the patient but also within

the actual structure of the establishment. Space was an important feature.

The building was purpose built to assist the restoration of the patients to

reason, and not as a place of secure confinement.

The Tukes were one of the first to exercise moral management as the primary

mode of treatment for the insane. They paid little attention to medical

forms of treatment; placing most emphasis on a therapeutic and benevolent

style of treatment.

Foucault's history of Tuke

Asylum as segregation

Foucault says that although "Tuke's gesture... is regarded as an act of

liberation. The truth was quite

different... The Retreat would serve as an instrument of segregation: a

moral and religious segregation which sought to reconstruct around madness

a milieu as much as possible like that of the community of Quakers." He

quotes Samuel Tuke:

"... there has also been particular occasion to observe the great loss,

which individuals of our society have sustained, by being put under the

care of those who are not only strangers to our principles, but by whom

they are frequently mixed with other patients, who may indulge themselves

in ill language, and other exceptionable practices. This often seems to

leave an unprofitable effect upon the patients' minds after they are

restored to the use of their reason, alienating them from those religious

attachments which they had before experienced; and sometimes, even

corrupting them with vicious habits to which they had been strangers."

Fear centred treatment

Foucault quotes Tuke on fear:

"The principle of fear, which is rarely decreased by insanity, is

considered of great importance in the management of the

patients."

This passage continues (not quoted by Foucault):

"But it is not allowed to be excited,

beyond that degree which naturally arises from the necessary regulations of

the family. Neither chains nor corporal punishment are tolerated, on any

pretext, in this establishment".

A further quote on fear, not quoted by Foucault is:

"In an early part of

this chapter, it is stated, that the patients are considered capable of

rational and honourable inducement; and though we allowed fear a

considerable place in the production of that restraint, which the patient

generally exerts on his entrance into the new situation; yet the desire

of esteem is considered, at the Retreat, as operating, in general,

still more powerfully"

The construction of self-restraint

Foucault argues that "at the Retreat the partial suppression of physical

constraint

was part of a system whose essential element was the construction of a

"self-restraint" in which the patient's freedom, engaged by work and the

observation of others, was ceaselessly threatened by the recognition of

guilt. Instead of submitting to a simple negative operation that loosened

bonds and delivered one's deepest nature from madness, it must be

recognised that one was in the grip of a positive operation that confined

madness in a system of rewards and punishments, and included it in the

movement of moral consciousness. A passage from a world of Censure to a

universe of Judgement. But thereby a psychology of madness becomes

possible...

The science of mental disease

The science of mental disease, as it would develop in the asylum, would

always be only of the order of observation and classification. It would not

be a dialogue. It could not be that until psychoanalysis had exorcised this

phenomenon of observation, essential to the nineteenth-century asylum, and

substituted for its silent magic the powers of language.

Is Foucault arguing that asylum psychiatry only observes madness,

whilst psychoanalysis has a dialogue with it? Or that asylum doctors did

not converse with their patients, whereas psychoanalysts do?

No longer repression, but authority

Surveillance and Judgment: already the outline appears of a new personage

who will be essential in the nineteenth century asylum. Tuke himself

suggests this personage, when he tells the story of a maniac subject to

seizures of irrepressible violence. One day while he was walking in the

garden of the asylum with the keeper, this patient suddenly entered a phase

of excitation, moved several steps away, picked up a large stone, and made

the gesture of throwing it at his companion. The keeper stopped, looked the

patient in the eyes; then advanced several steps towards him and

""in a resolute tone of voice ... commanded him to lay down the

stone".

As he approached the patient lowered his hand, then dropped his weapon.

"he then submitted to be quietly led to his apartment"

Something had been born, which was no longer repression, but authority.

1.7.1967 Idiosyncratic structuralist?

In the cartoon, Foucault explains his ideas to three other structuralists.

Levi-Strauss is distracted, Lacan psycho-analyses him and Roland Barthes

looks friendly, but unconvinced.

|

Foucault was a philosopher and historian of systems of

thought. I have seen

him identified with

structuralism or

post-modernism and post-structuralism.

But, reading between the lines, his ideas and concepts suggest

to me that

he would not have enjoyed being labelled, or put into boxes.

To have put

himself into a certain box, in academic terms, would have

meant going

against his own ideas or thoughts. He thought that if you

become wrapped

into a set of 'truths' of a specific knowledge or theory, you

cease to

learn - as you think you know the answers. Then you have

imprisoned

yourself by taking these ideas as true or common knowledge.

I sense if he was to let himself be portrayed under a certain

terminology

he would also then be caught up into a discourse of a certain

set of

language that is unified by common assumptions or beliefs

within an

academic context

(Foucault, M. 1980 Power & Knowledge, Chapter 6).

November 1971: Foucault carries on explaining himself. This time

to

Noam Chomsky

|

""I admit to not being able to define, nor for stronger reasons

to propose, an ideal social model for the functioning of our scientific and

technological society. On the other hand, one of the most urgent tasks,

before everything else, is that we are used to consider, at least in our

European society, that power is in the hands of the government and is

exerted by some particular institutions such as local government, the

police and the army, These institutions transmit the orders, apply them and

punish people who do not obey.

But I think that political power is also exerted by a few other

institutions which seem to have nothing in common with the political power,

which seem to be independent, but which actually are not. We all know that

universities and the whole education system that is supposed to distribute

knowledge, we know that university and the whole educational system

maintain the power of a certain social class and exclude the other social

class from this power. Psychiatry, for instance, is also apparently meant

to improve mankind, and the knowledge of the psychiatrists. Psychiatry is

also a way to implement a political power to a particular social group.

Justice also.

It seems to me that the real political task in a society such as ours is to

criticise the working of institutions, that appear to be both neutral and

independent. To criticise and attack them in such a manner that political

violence that has always exercised itself obscurely through them will be

unmasked, so one can fight against them. If we want right away to define

the profile and the formula of our future society, without criticising all

the forms of political power that are exerted in our society, there is a

risk that they reconstitute themselves, even though such an apparently

noble form as anarchist unionism."

|

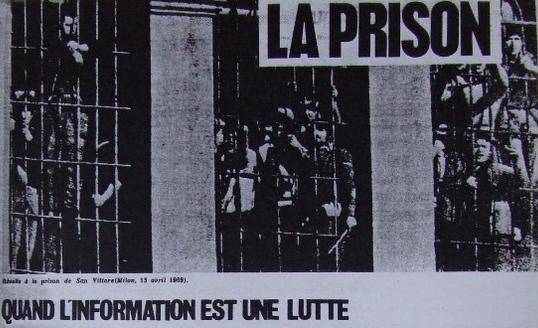

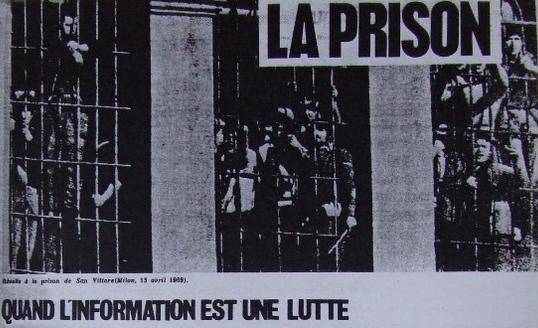

Prison: When information is a struggle [political fight]

Michel Foucault was a campaigner against prison secrecy. 8.2.1971

(France)

Manifesto of the Le Groupe d'information sur les prisons signed

by Jean-Marie Domenach, Michel Foucault et Pierre Vidal-Naquet.

Images of knowledge, observation, struggle and power run through the issues

that are discussed below. Le Groupe d'information sur les prisons

was a radical alliance of left wing political activists in local cells who

linked with nearby prisons to secure information about what was happening

inside them. Jean Paul Sartre was one of the people who published the

information in his newspapers. This new technique of political struggle

used information from below. Foucault's book Surveiller et Punir

considers information gathered from above people. It is about information

that can only be seen by people who gather it, not by those it is gathered

about.

|

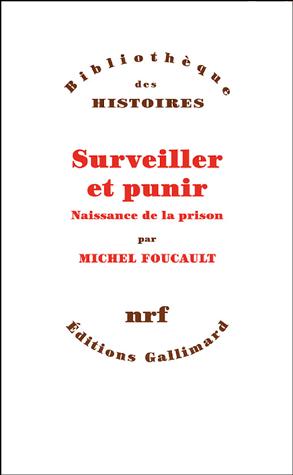

February 1975 Surveiller et Punir - Observe and punish -

Discipline and punish - Naissance de la prison - Birth of the

prison.

We can consider

Discipline and Punish as Foucault's contrast and

comparison

of the modern 19th century prison (beginning with Bentham's Panopticon

idea) with what had gone before.

PART ONE

TORTURE is about what happened before the 19th century

PARTS TWO, THREE AND FOUR ON

PUNISHMENT - DISCIPLINE - AND PRISON are about

the new system.

|

|

|

5.1.1757 France: Robert-François Damiens, an

unemployed domestic

servant, rushed at King Louise 15th of France, stabbing him with a knife

and inflicting a (not-fatal) wound.

|

Louis 15th of France was five years old when he came to the throne in 1715.

He ruled alone from 1743.

|

|

|

Le supplice [torment - torture] de Damiens le régicide [king-

killer] - illustration from Foucault

|

Damiens was condemned ( 1.3.1757) as

a regicide (a person who kills a king) and sentenced to be publicly drawn

and quartered, by horses. The execution was carried out on 28.3.1757

|

|

Classical (Reform) Criminology

The Italian Cesare

Beccaria and the Englishman

Jeremy Benham are

the two best known people now called

Classical Criminologists. Beccaria thought of prisons as

nasty secret places, but Bentam thought they could be reformed

to become the main means of rational punishment, replacing the barbarities

that Foucault calls

torture.

Beccaria and Bentham were both honoured by the French Revolutionaries who

abolished the

regime of torture (1670) and replaced it with a rational

penal code (1791).

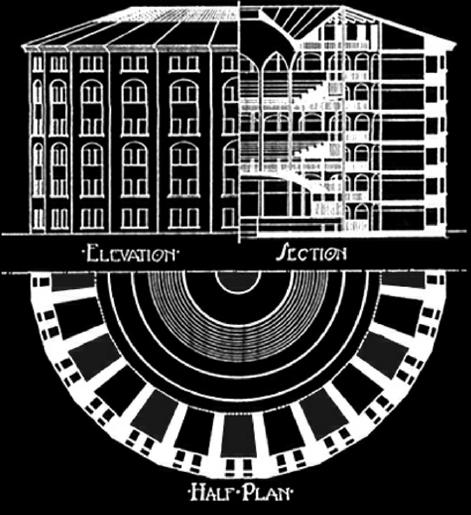

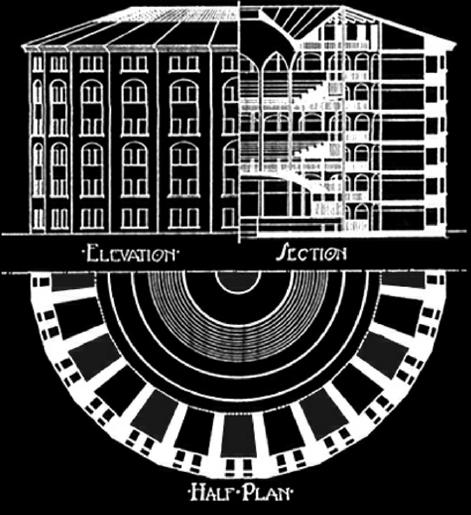

At the end of the eighteenth century,

Jeremy Bentham designed a panopticon, or model instition. He

thought that principles involved i this could

be used to re-design the rest of society.

In the panopticon a supervisor in the centre can see everything that anyone

in the building is doing.

|

1791

The Principle of the Panopticon or Inspection House

by

Jeremy Bentham

Panopticon is derived from Greek, and the best I can do in translating is

all-seeing. It had been used (1768) for a kind of telescope. Bentham used

it in his letters of 1787 (published 1791) for his plan for a circular

institution in which all the inmates cells could be seen from the centre,

where the inmates knew anything they did could be seen, but could not see

if they were being seen. Inspection House (see below) conveys the meaning

in English. The word inspect was translated into French by Foucault as

surveiller, which now means to supervise or have authority over, but comes

from a word (veiller) for staying awake to keep guard whilst others sleep.

In 1794, Parliament

backed this scheme,

as a prison plan.

The foundations were laid.

But, in January

1803, Bentham was told

the Government could not find the funds

|

Millbank

Penitentiary, opened in 1832, was a modified version

of Bentham's plan which the Government built on the

foundations Bentham laid. It was a distinctive feature on London maps in

the 19th century.

|

Bentham thought that the same plan could be used for schools, orphanages,

workhouses and

many other institutions.

Read Bentham on the Panopticon

Morals reformed - health preserved - industry invigorated instruction

diffused - public burthens lightened - Economy seated, as it were, upon a

rock - the gordian knot of the Poor-Laws are not cut, but untied - all by a

simple idea in Architecture! - Thus much I ventured to say on laying

down the pen - and thus much I should perhaps have said on taking it up, if

at that early period I had seen the whole of the way before me. A new mode

of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without

example: and that, to a degree equally without example, secured by whoever

chooses to have it so, against abuse. - Such is the engine: such the work

that may be done with it. How far the expectations thus held out have been

fulfilled, the reader will decide.

Read Foucault on the Panopticon

"Let penalties be regulated and proportional to the offenses,

let the death sentence be passed only on those convicted of murder, and let

tortures that revolt humanity be abolished."

Thus, in 1789, the chancellery summed up the general position of the

petitions addressed to the authorities concerning tortures and executions

Generally speaking, all the authorities exercising individual control

function according to a double mode:

|

binary division and branding (mad/sane; dangerous/harmless;

normal/abnormal)

coercive assignment of differential distribution (who he is; where

he must be; how he is to be characterised; how he is to be recognised; how

a constant surveillance is to be exercised over him in an individual way,

etc.)

|

The constant division between the normal and the abnormal, to which every

individual is subjected, brings us back to our own time... the existence of

a whole set of techniques and institutions for measuring, supervising and

correcting the abnormal brings into play the disciplinary mechanisms...

All the mechanisms of power which, even today, are disposed around the

abnormal individual, to brand him and to alter him, are composed of those

two forms from which they distantly derive.

Bentham's Panopticon is the architectural figure of this composition

Read Louise Warriar and others on

Surveillance

Moderated surveillance is a feature of modern government. Modern because

it relates to the development of the bureaucratic state and industrial (as

distinct from agricultural) economies - Moderated because the camera

watching the streets is limited by laws (unlike the total surveillance

described by George Orwell in Nineteen Eighty Four) - Government by

surveillance because the subject is controlled by the knowledge that the

subject is watched.

Technology makes surveillance possible, but our social theory provides the

framework that makes it meaningful and limits it.

To look at this social theory, we will first analyse the work of Jeremy

Bentham (1748-1832), then look at the analysis of Michel Foucault (1926-

1984), and proceed, in the light of this, to discuss surveillance by closed

circuit television (CCTV) cameras.

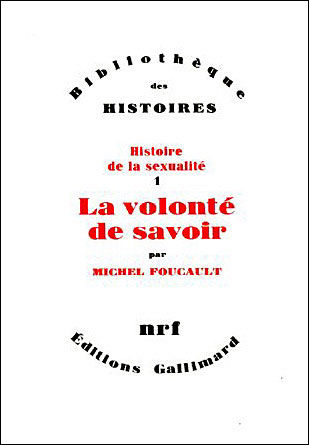

1984 Histoire de la sexualité

volumes 2 and 3.

25.6.1984 Death of Michel Foucault

|

1976 Histoire de la sexualité 1 - La Volonté de

savoir (The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: The will to know).

English

translation 1978

(The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction).

|

Sexual repression and

incomplete liberation - a two-part story

The sexual repression story

Foucault begins:

"For a long time, the story goes, we supported a Victorian regime, and we

continue to be dominated by it even today. Thus the image of the imperial

prude is emblazoned on our restrained, mute, and hypocritical

sexuality".

"At the beginning of the

seventeenth century a certain frankness was still common, it would seem.

Sexual practices had little need of secrecy; words were said without undue

reticence, and things were done without too much concealment"

But twilight soon fell upon this bright day, followed by the monotonous

nights of the Victorian bourgeoisie. Sexuality was carefully confined; it

moved into the home. The conjugal family took custody of it and absorbed it

into the serious function of reproduction. On the subject of sex, silence

became the rule..."

|

Photograph of

Queen Victoria by John Jabez Edwin Mayall

(1813-1901)

taken on

1.3.1861. If the date is correct, this was taken before the

death of her husband, Albert on 14.12.1861. Mayall

sold thousands of such

images to the public in the 1860s.

Photograph of

Queen Victoria by John Jabez Edwin Mayall

(1813-1901)

taken on

1.3.1861. If the date is correct, this was taken before the

death of her husband, Albert on 14.12.1861. Mayall

sold thousands of such

images to the public in the 1860s.

|

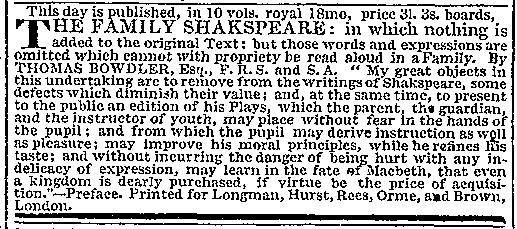

Thomas Bowdler, 11.7.1754 - 24.2.1825

Has given his name to the practice of removing or altering material

considered improper or offensive - Bowdlerisation.

The Times,

10.10.1819 page 4.

As written, Iago in Shakespeare's

Othello (1604) says "I am one,

sir, that comes to tell you your daughter and the Moor are now making the

beast with two backs." [having sex].

Bowdler altered to "I am one, sir, that comes to tell you your daughter and

the Moor are together."

Bowdler says

"I wish it were in my power to say of indecency as I have said

of profaneness, that the examples of it are not very numerous.

Unfortunately the reverse is the case. Those persons whose acquaintance

with Shakspeare depends on theatrical representations, in

which great alterations are made in the plays, can have little idea of the

frequent recurrence in the original text, of expressions, which, however

they might be tolerated in

the sixteenth century, are by no means admissible in the

nineteenth."

Foucault continues:

But have we not liberated ourselves from those two long

centuries in which the history of sexuality must be seen first of all as

the chronicle of an increasing repression? Only to a slight extent, we are

told. Perhaps some progress was made by Freud;...

We are informed that if

repression has indeed been the fundamental link between power, knowledge,

and sexuality since the classical age, it stands to reason that we will not

be able to free ourselves from it except at a considerable cost:...

Hence,

one cannot hope to obtain the desired results simply from a medical

practice, nor from a theoretical discourse, however rigorously pursued.

Thus, one denounces Freud's conformism, the normalizing functions of

psychoanalysis, the obvious timidity underlying Reich's vehemence

Foucault's doubts about the repressive hypothesis

"The doubts I would like to oppose to the repressive hypothesis

are aimed less at showing it to be mistaken than at putting it back within

a general economy of discourses on sex in modern societies since the

seventeenth century.

Why has sexuality been so widely discussed, and what

has been said about it?

What were the effects of power generated by what

was said?

What are the links between these discourses, these effects of

power, and the pleasures that were invested by them?

What knowledge

(savoir) was formed as a result of this linkage?

The object, in short, is

to define the regime of power-knowledge-pleasure that sustains the

discourse on human sexuality in our part of the world.

The central issue,

then (at least in the first instance), is not to determine whether one says

yes or no to sex, whether one formulates prohibitions or permissions,

whether one asserts its importance or denies its effects, or whether one

refines the words one uses to designate it; but to account for the fact

that it is spoken about, to discover who does the speaking, the positions

and viewpoints from which they speak, the institutions which prompt people

to speak about it and which store and distribute the things that are said.

What is at issue, briefly, is the over-all "discursive fact," the way in

which sex is "put into discourse.""

Charles Joseph Jouy (born about 1827) and the construction of

knowledge

Repression is part of the construction of a discourse (field of

knowledge) about sex

Consider the construction of our knowledge or discourse about

paedophilia

|

In the

1867 story of

Charles Joseph Jouy and Sophie Adam

we see how the histories of psychiatry, criminology and sex

inter-twine. We can also see how Foucault is working on the same

labyrinth of ideas

throughout his work.

Foucault's account of Jouy (aged 40), Sophie (a girl) and Sophie's unnamed

friend, is based on an account by two psychiatrists, Henry François

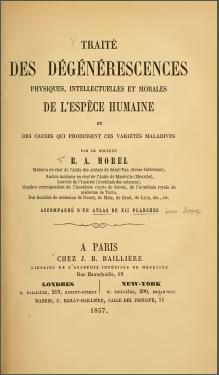

Auguste Bonnet and Jules-Amédée Bulard, published in 1868: a

Medical-legal report on the mental state of Charles-Joseph

Jouy, charged with an

outrage to morals [a sexual crime, rape or indecent

exposure]. Bonnet and Bulard worked at the asylum at

Maréville where Jouy was confined and studied. Their work

was an extension of that of another psychiatrist, previously at the same

asylum,

Benedict Augustin Morel.

Foucault gave two separate versions of this story. The first was in a

1974/1975 lecture, the second in the first volume of his

History of

Sexuality (1976).

I have drawn on both.

|

Charles-Joseph Jouy was about forty years old in 1867. Sophie Adams appears

to have been under eleven years old. Jouy was an illegitimate child whose

mother had died when he was young. Foucault describes him as simple minded

and "more or less the village idiot". He was poorly educated, took whatever

badly paid work he could find, lived a solitary life and tended to get a

bit drunk.

|

One day, Sophie's mother was disturbed by what she found when washing

Sophie's clothes.

On enquiry it emerged that Sophie and a friend had been

masturbating Jouy (in exchange for gifts?) and on the last occasion things

had got out of hand and Sophie had been "almost, partly, or more

or less raped".

|

|

|

Foucault's review of the

evidence suggests that Sophie and her friend had

considered the earlier incidents of masturbating Jouy as an adventure and

had told a villager about them without it being taken as alarming.

The

"almost, partly, or more or less raped" was different, but Sophie did not

tell her mother for fear of being slapped.

Jouy had given the girls money

which they had spent on roasted almonds at the local fair.

|

The picture of

domestic violence is from a woodcut in

"Jack and Jill and Old Dame Gill", a sheet published by J.

Kendrew in York about 1820.

|

French Penal Code of 1810

Attacks upon Morals

330. Whoever shall commit any public outrage against modesty, shall be

punished with an imprisonment of from three months to one year, and a fine

of from 16 to 200 francs.

331. Who shall commit the crime of rape, or shall be guilty of any other

attack upon the modesty, consummated or attempted, with violence, against

an individual of either sex, shall be punished with solitary imprisonment.

332. If the crime has been committed upon the person of an infant, under

the age of fifteen years complete, the criminal shall undergo the penalty

of hard labour for time.

|

A pure object of knowledge

"The thing to note is that they went so far as to measure the

brainpan, study the facial bone structure, and inspect for possible signs

of

degenerescence the anatomy of this personage who up to that

moment had been an integral part of village life; that they made him talk;

that they questioned him concerning his thoughts, inclinations, habits,

sensations, and opinions. And then, acquitting him of any crime, they

decided finally to make him into a pure object of medicine and knowledge -

an object to be shut away till the end of his life in the hospital at

Mareville, but also one to be made known to the world of learning through a

detailed analysis.

Foucault is making the point that, whatever the rights and wrongs of the

incidents that led up to his confinement (*), Charles-Joseph Jouy, village

idiot

aged 40, has now become a lifetime object of science for the new

psychiatry. From the lives of many such as him, a new system of knowledge,

a new way of seeing things, is being created.

Foucault is considering how three types of abnormal (not normal)

individuals were conceptually constructed by science. He calls these the

"monster" - the "little masturbator" and the "individual who cannot be

integrated within the normative system of education". Jouy considered as a

paedophile (a term not then in use) seems to fit each category. By today's

standards, he was a monster:

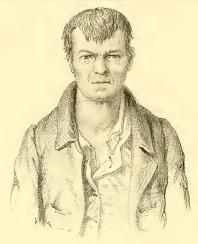

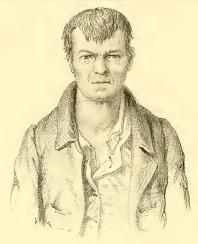

Joseph (below) is a weaver, aged 55 (about 1857). Morel describes him as

having a deeply corrugated face with a characteristic expression that

denotes ordinary intelligence. He is not someone who drinks excessive

alcohol. He is the father of "cretins" and so Morel

says that we must look in his ancestry and in his features for the

evidence of hereditary transmission. Apparently, his father and

grandfather were semi-cretins, and their [other?] children have

successively died young. Cretinism is associated with goitre - an

enlargement of the thyroid gland.

|

Joseph has only elements of hereditary defect (les éléments

de la continuité de l'espèce). He is a tall, but his

head is disproportionately expanded in its bi-lateral diameter. The

posterior portion is flattened. Cheekbones are salient. His nose is very

enlarged at the base (épaté). His upper lip is an abnormal

height. [I think Morel refers to the area between the nose and the lip. He

says cretins have a similar feature]. His lower jaw is enormous. His

ears are crooked and misshapen. Morel says he has incipient goitre.

|

Solemn discourse "overlays" everyday theatre

Foucault argues that the repression of familiar discussion of sex,

enforcing a polite, sanitised attitude in which children did not "talk

about all these things aloud"

(the sexual repression story), as happened in the period we call

Victorian, was necessary for "institutions of knowledge and power" to

establish the scientific discourse as the overlying one.

At the same time as Jouy was becoming an object of scientific study,

Foucault says:

"One can be fairly certain that during this same period the Lapcourt

schoolmaster was instructing the little villagers to mind their language

and not talk about all these things aloud. But this was undoubtedly one of

the conditions enabling the institutions of knowledge and power to overlay

this everyday bit of theatre with their solemn discourse.

So it was that our society - and it was doubtless the first in history to

take such measures - assembled around these timeless gestures, these barely

furtive pleasures between simple-minded adults and alert children (*), a

whole

machinery for speechifying, analysing, and investigating."

|

Index and contents

Questioning histories

Patterns of power and concepts

of self

Born

History penetrates his

childhood

Madness and Psychiatry

Reform psychiatry -

Tuke

Tuke on Tuke

Foucault on

Tuke

Was he a

structuralist?

Foucault explains

himself

Penology, Criminology and Sociology

Information on prisons

Observe and re-

form

Old fashioned torture

Reform Penology,

Criminology and Sociology - Bentham

Bentham on

Bentham

Foucault on

Bentham

History of sex

Sexual repression

Bowdler

Incomplete

liberation

Foucault's doubts about the repressive hypothesis

Jouy and the construction of

knowledge

Solemn discourse "overlays" everyday theatre

Sex and Sexuality

Short bibliography

|

Time Line

Time Line

Social Science Dictionary

Social Science Dictionary

Durkheim and Weber's contrasting imaginations

Durkheim and Weber's contrasting imaginations

Andrew Roberts' home page

Andrew Roberts' home page

Society and Science home page

Society and Science home page

Chronological Foucault extracts

Chronological Foucault extracts  Other extracts

Other extracts  People and ideas entry

People and ideas entry

Works

Works  Reviews

Reviews