Social Science Dictionary with a Durkheim bias

Words to describe social reality

See also mind words other wordsSocial Science History

Society and Science History TimeLine

Durkheim index: "Consider social facts as things"

people

Index

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Able

Absolute

Academia

Accommodation

Achievement

Acting

Action

Action Frame of

Reference

action research

Actor

Adaptation

Advertise

advocate

and advocacy.

aetiology

Affectivity

Age

Agency

Agent

Agriculture

algorithm

Alienation

Altruism

Anarchy

Animal

Ancient Regime

Anomie and

Anomy

Anthro-

Anthropology

anti-psychiatry

Anxiety

a priori

Argumentation

Art

Articulate

Ascribe

Ascription

Assimilation

association of ideas

astrology

atavism

Auburn model

Authority

Authoritarian

Autobiography

Autoethnography

Autonomic nervous system

Atomism

Autonomy

Autocrat

average

Average man

Barbarism

Base

Behaviour

Beast

behavourism

Belong

Bell curve

Big data

Binary Opposition

Bio-

Biography

Biology

Biological identity

Biopower

Biological

Organism

Birth

Bisexual

Blemished

Body

Body Image

Body

Language

Body, mind and society readings

Bond

Borough

Bourgeoisie

Brain

Branding

Brute

Brutalisation

Bully

Bureaucracy

Business

Capital

Capitalism

Carceral

Care

Carer

Career

case studies

Cash nexus

Caste

categorical

imperatives

Celibate

Celibate vocation

Censor

census

Central Nervous System

Centred structure

Ceremony

Change

Character

charisma

chart

Chemistry

Childhood

Child abuse

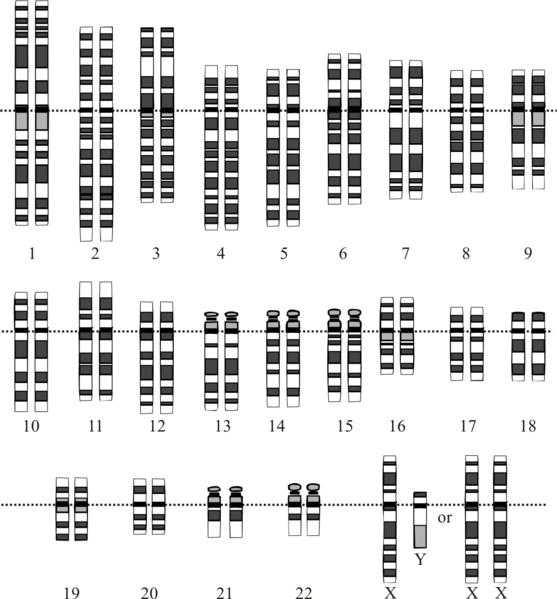

Chromosomes

Church

Circumstances

Citizen

City

civil

inattention

Civil law.

Civilisation

Clan

Class

Classical

Classical

criminology

Classical

economists

Classification

Clothes

code

Cohesion

Collaborate

Collaboration

Collective Conscience

Collective Mind

Collectivity orientation

Collective Representations

combination

Commerce

Commodification

Commodity

Common Conscience

Common Sense

common

law

Compassion

comprehend

Communicate

Communication

Communicative Action

Communism

Community

Community of

women

Community Disintegration Theory

Competition

Complexity theory

computing

concept - conceive

Conception

conception

Conflict

Conjugal society

Conjuncture

Consanguine

Consequences

Conservative

Conscience

Consciousness

Constitutional

Constraint

Constructed

Order

Construction

constructivist structuralism

Consumer

Consumer society

Consumers voice

Consumption

Content Analysis

Context

Contextualise

Continuity

Contingent

Contract

Contradiction

Control

control group

Converge

Convergence of

theories

Convention

conversation in

gestures

Cooperate

Cooperation

Cooperativism

Core Gender

identity

Corporate

Corporate psychopath

Corporatism

correlation

Countryside

Covenant

Craft

Crime

Crime and insanity

Criminal law.

Criminal career

Criminology

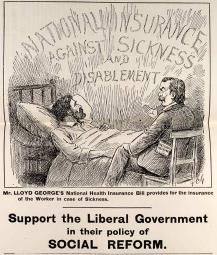

Crisis

Crises since 1945

Critical

Critical theory

critical thinking

Culte du moi

Cultural capital

Cultural Constructs

Cultural Goals

Cultural

heritage

Cultural Ideals

Culture

Custom

Cybernetics

Dasein

data

Database

Data sets

Decentred structure

decode

Deconstruct

defective

define

Degenerate

Degeneration Theory

Degradation

Dementia

Democracy

Demography

Demonise

Dependency

Depression

describe

Descriptive

Desire

Despotic

Detached

Determine

Determinism

Development

Deviance

Deviation -

statistical

Dialectic - dialectical

Dialogue

dialogue

Diaspora

Dictator

Dictatorship of the proletariate

Differentiation

Diffuseness

digital

Digital age

Dimension

Disabled

Discontinuity

Discriminate

Discourse

Disease

Disintegration Theory

Discipline

Disownment

Disorder

Disposition

Dispositif

Dispositifs techniques

Distinction

Distress

Diversity

Divine Right of Kings

Division of Labour

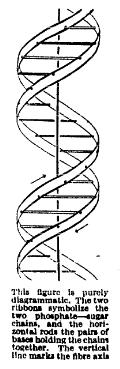

DNA

documentary research

dogma and dogmatism

Domestic

Domestic labour

Domestic

violence

Domination

Drug

Dwell - dwelling

Dynamics

Dysfunctional

Ecology

Economics

Economic capital

Economists

the Economy

Ecosystem

Education

Effects

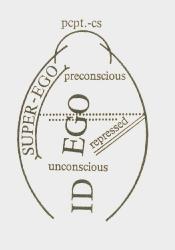

ego (Freud)

Egoism

Embodied Self

Embodiment

Emigration

Emotion

empirical

empiricists and

empiricism

Employment

empowerment

Engineer

Enlightenment

Environment

Epigenetics

Episteme

epistemology

Equality

Equilibrium

essence

Essentialism

Estrangement

Ethics

Ethnicity

Ethnicity and race

Ethnic indicators

Ethnic statistics

Ethno-

Ethnography

Ethnology

Ethnomethodology

etiology

Eugenics

Evangelical Revival

(British)

Everyday life

Evolution

Exchange

existence

Existentialism

existentialism

Exclude

Exnomination

Experience

experiments

Expositor

Extended family

External

Extrude

Facts

fairy tales

Family

Family statistics

Family today

Fan

Fandom

fascist

Father

Felicific calculus

Fear

Feminism

Fetish

Feudalism

Field

field work

figure

figurational

sociology

Finkelstein on disability

Fisher's squares

Fisher's P values

focus

focus

group

Folklore

Folkways

Fordism

formulas

Force

Form

Frankfurt school

Freedom

Friend

Function

Functional

Functionalism

Game

Garden

Gemeinschaft

Gen-

Gender

Gender identity

Gendering

Gender nonconforming

Genes

general will

Generation (birth)

Generation

(construction)

Genetics

Genitals

Genome

Genotype

Gens

Geo-

Geography

Geology

Geometry

Gesellschaft

Gestalt

Gift

Globalisation

Goal

Attainment

God

Governance

Government

Government rule

graph

grounded theory

Group

Habit

Habitualisation

Habitus

Happy

hardware

hardware times

Harmony

Hegemony

Health

Heart

Hermeneutics

Hereditary

Heritage

Herrschaft

Hetero

Heteronomy

Heteronormative

Heterosexual

Heterosexual matrix

Hey You!

Hierarchy

Hierarchy and power

High

History

Historic Social Structures

historical research

Historical materialism

Hoax theory

Holism

Holy

Home

Homicide

Homo

Homosexual

Horde

Horizontal segregation

House

Household

Houshold

Economy

Human capital

Human Ecology

Humanism

Humanity

Humanity nation family

Human Rights

hysteria

hypothesis

icon

id (Freud)

ideal

types

ideas

Idealist

Identity

Identity politics

Ideology

Imagination, society and science

Image

Immigration

impairment.

Imperative

Incest

Incest taboo

indicators

Individual

Individual and

society

Individualisation

Individualism

Industrial

Industrial

revolution

Industrial society

Inequality

Infantilise

Information

Information age

Information Technology

Insane

Inscribe

Institute

Institution

institutional

institutional racism

institutionalisation

Institutions

and

Mind

Integration

Intellect

Intellectual

Intelligence

Inter...

Interaction

Internal

Internalise

Internet

Interpellate

interpret - interpretation

Interpretive sociology

Intervention

Intra...

Involvement

isomorphic

structures

Kinship

Knowledge

Knowledge types

Label

Labour

Labour theory of

value

Language

Latency

Latent

Latent class

analysis

Late modern

latin

square

Law

Learning

Legitimate

Leisure

Lexicology

Liberal

Liberalism

libido (Freud)

library

Lifeline

Linguistics

Lifeworld

Liminal

Liquid modernity

logic

Logical Positivism

Love

Macht

Mad

Madness

Mad studies

Magic

Magistrate

Man, Mankind,

Humanity

Management

mana

manga

Marginal

Utility

Marginalise

Market

Marketing

Market

Marketing

Marriage

Marxism

Mass Media

Mass Society

Material

Materialist

Mathematics

Matriarchal

Matrix

McCarthyism

Meaning

mechanical

solidarity

mechanical

solidarity

Media

media research

Medical model

Medieval

Meetings

Memory

Men's community

Mental

Mental disorder

Mental distress

Mental health

Mental illness

mental patient

Meta-

Metalanguage

metaphysics

metatheory

Methodological

individualism

Methodology

Microcosm

Migration

Mind

Mind and brain

mixed methods

Mode of Production

models

Modern

Modernity

Modern State

Modesty

Monarch

moral

Moral career

Moral insanity

moral

panic

Moral rules

Morals

Moral

Sciences

moral

statistics

Mores

Mortification

Mother

Motivation

Movement

Movement intellectuals

museum

Mutual

Mutuality

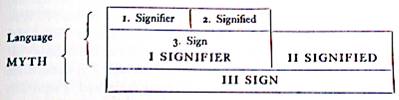

Myth

Narrative

Nation

Natural

Natural World

Natural law

Natural science

Nature

Nazi (National Socialist)

neo-classical criminology

neo-liberal

Nervous System

Networks

Network society

Neuroscience

Neurosis

Neurotic

Nexus

Nodes

Normal

Normal curve

Normal person

Norms

Nourish

Nuclear family

Null hypothesis

Nurture

Obedience

Objective

Objectivism

Obese

Obligation

observation

obsession

Occupation

Occupational career

Occupational

segregation

open access

open

learning

operationalise

Oppression

Order

organic

solidarity

organic

solidarity

Organisation

Organised society

Organism

Orientation

Other

Outsider

Overdetermination (Althuser)

Paedophilia

Pan-

Panopticon

Paradigm

Paradigm shift

Parallel

Parallelism

Participate

participant observation

Particularism

Parts of self

Parts of society

Passage

passion

Paternalism

Path

patience

patient

Patient to person

Patriarchal

Patriarchy

Patrimonial

Pattern

Pattern

Maintenance

Pattern

Variables

Pederasty

Peer

Peer Assisted

Learning

Penal

Penal Code

Penality

Penalty

Performance

Performativity

permutation

person

Person or less than

Person to patient

Personal branding

Personality

Perspective

Phenomenological

Phenotype

Philadelphia system

Philosophy

photo

Phrenology

Physics

Picturing the brain

Picturing the mind

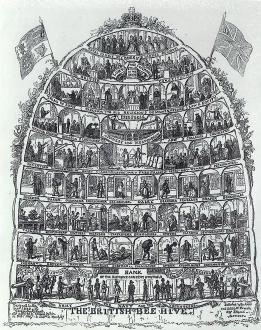

Picturing society

plastic

Pluralism

Poetry

Political and

Politics

Political

Economy

Popular culture

population (statistics)

Population

Position

Positive law

Positive Criminology

Positivism

post-

Post industrial

Postmodern

Postmodernism

Postmodernists

Postnatal

depression

Poverty

Power

Power: gun and ideas

Power:

Hierarchical

Power:

Pluralist

Practice

Pragmatics

Pragmatism

Praxis

Precedent

Pregnancy

Prejudice

Prerogative

Prescription

Present

Presentation

Prices

Primary Group

primary research

Primary

socialisation

Primitive

Prison

prisoner's dilemma

Private

probability

Process

Processor

Production

Profane

Progress

Proletariat

Property

psychiatry

psychoanalysis

Psychology

Psychological

Psychopath

Psycho Politics

Psychosis

Psychotic

Psychotropic

Public

Public Discourse

Public

Opinion

Public

Sphere

Punishment

qualitative data

quantitative data

questionnaires

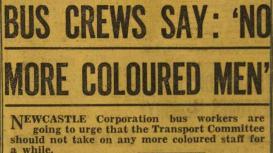

Race

Racial

prejudice

Racial segregation

Racialism

Racism

random

Rate

rationalists and rationalism

Real

Real and

simulated

Realism

Rearticulate

reason

Reciprocal Development

Recognise

Recontextualise

recorded sound

Recovery

reductionist

(Durkheimian swearing)

reflection

Reflex arc

Reflexive

Reflexive autocritique

Reflexive modernisation

Reflexive modernity

Regress

regression analysis

regression to the mean

Regulate

reification

(Weberian swearing)

Relativism

reliable

reliable indicators

Religion

Represent

Reproduction

research

Resistance habitus

Response

Revolution

Rhythm

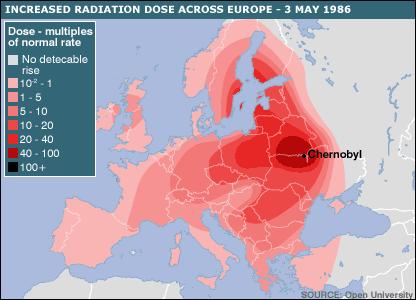

Risk

Risk society

Rite

Rite of Passage

Ritual

Robotics

Role

Rothamsted squares

Rules

Rural

Sacred

Sacrifice

Sad

sample

Savagery

Schema

Scheme

Schizophrenia

School

Science

Scientific socialism

scientology

scouts

Secondary research

Secondary

socialisation

second wave

Segregation

Self

self-dependence.

self-determination.

self development

self-help

Self knowledge

Self Orientation

Semiology

semiology

semiotics

Sentiments

Separate system

sequential

Service recipient

Service user

Settlement

Sex

Sexuality

Sexual

orientation

Sex with

children

Shame

Sharia

Shekhinah

Sick role

Side effects

Sign

significance

Signification

Signified

Signifier

Signify

Silent system

Simulated

skills

Slavery

snowball sampling

Social

Social Action

Social approach

to health

Social Behaviourism

Social capital

Social Character

Social Construction

Social

Contract

Social Darwinism

Social Dynamics

Social facts

Socialism

Social media

Social model

Social model of disability

Social model of distress

Social model of health

Social Movement

Social Network

Social Order

Social

psychology

Social

Science

Social Space

Social Statics

social

statistics

Social Structure

Social (sub) Structures

Social Structures in history

Social

System

Social System Needs

Social System Parts

Socialisation

Socialism

Society

Society as an active force

Society as body - organism and/or system

Society's Parts

Sociology

software

software times

Solidarity

Solid modernity

Soul

Sovereign

Space

Spacetime

Spatial

Specificity

Speech

Spontaneous

Order

spread

standard deviation

standpoint theory

State

State of

Nature

Statics

Statistical

deviation

statistical lies

statistically significant

statistics

Status

Stereotype

Stigma

Stimulus response

Stop thief!

Strain

Strata

Stratification

Stress

Structuralism

structuralist constructivism

Structure

structural functionalists

Subconscious

Subculture

Subject

Subjection

Subjective

sub-systems of human action

Successful psychopaths

Suicide

super-ego (Freud)

Supernatural

Superstructure

surveillance

Survivals

Survivors

Survivors movement

Survivor's history

Survivor research

Symbol

symbolic annihilation

Symbolic capital

symbolic

interaction

symbolic violence

System

Systems theory

table

Taboo

Tacit

Technologies

Temporal

Terror

Terrorism

Terrorist

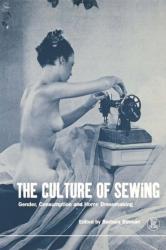

Textiles

Thatcherism

Them and us

Theology

Theosophy

theory

therapeutic comunity

third

wave

Time

time

time series

tissue

Token

Tokenism

topology

total

institution

totalitarian

Torture

Totem

Trade

Tradition

Traditional society

Trajectory

Transgender

trauma

Tree

triangulation

Tribe

Truth

Type

Typification

Tyranny

Unconscious

Underlife

Unanticipated consequences

understand

Universalism

University

Urban

USA

Sociology

Utilitarianism

valid

valid indicators

Value

variable

Variation

Verstehen

Vertical segregation

Very modern

Victorian

Village

Violence

Virtual

Virtual

Community

Visual

Vocation

Voice

Voices

Wage

War

Wealth

Web

Wellbeing

Well of

loneliness

Weltanschauung

White Collar Crime

wireless

Woman

Women's community

Women's Movement

Work

Work based learning

World-view

world wide

web

worship

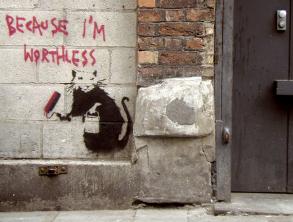

Worthless

Zeitgeist

| If you have not found it here: click the spider to try somewhere else: |

|

|

|

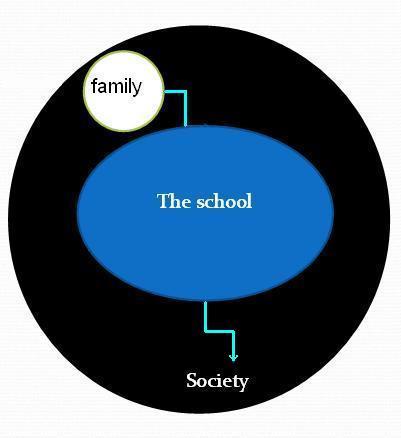

Society Society is the most general term in modern English for the body of institutions and relationships within which a relatively large group of people live. (Williams, R. 1976)

|

Society may not be visible, but its symbols are. Click on the fishing bird to know more. |

Is society real?

To some people, common sense says society is not real

.

Margaret Thatcher argued that it

does not exist. It could, however exist but

not be real in the sense that our bodies are real.

Some theorists treat the individual as real and society is

constructed by individuals. Such theories have been called

social atomism or methodolological individualism,

Following

Weber, structural functionalists argue that society comes into

being because of the

orientation of individuals. Robert Merton says:

"every aggregate of individuals who are in continuous contact

form a

society" ...

"individuals must adhere materially, but it is

still necessary

that there be moral links between them."

(Durkheim, E. 1893/1933

p.276)

Individual means something that cannot be divided: a unit complete in

itself. In the above quotations it refers to single human beings, which is

what we usually mean when we say "an individual". In this sense,

sociologists later than Durkheim have spoken of

"the self" in relation to

society. One can, of course, speak of an individual society.

"

It is ... only because behaviour is typically orientated toward the

basic values of the society that we may speak of a human aggregate as

comprising a society. (Merton, R. 1957, p. 141)"

Social holism is the opposite approach to social atomism. It means treating society as a whole that is more than adding up its parts, more than the construction of individuals. This was Durkheim's approach.

For Durkheim, society is originally everything, the individual

nothing: (See the Durkheim

index on society)

|

We speak of society, or parts of society, as being active when we refer to

our society as

nurturing us.

Eugène Delacroix's 1830 painting symbolises France as liberty leading the people bare breasted, possibly symbolising that she breast feeds the people.

|

Society's parts

Filmer

and

Locke

made different analyses of

family

and

politics

as parts of

society. Filmer argued that

political power

derives from family power, but Locke said that we

should not confuse:

paternal or parental power with

political power, or either of

them with

with

despotical power.

Hegel suggested that society

(the whole) has

three corners: the

State

(

politics),

Civil Society

(the

economy) and

Private

Society

(the

family).

One of the

activities of

social theorists has been to theorise about how the parts of

society

inter-relate.

USA

sociologists,

like Talcott

Parsons

tend to treat society as created by individuals, rather than a

reality in

itself. However, Parsons argues that individual actions are directed to

other people and that, in the inter-action of individuals, a

social system emerges. Society, therefore, emerges as a reality.

Robert Merton belongs to the same school of thought

(Structural

Functionalism)

as Parsons.

Parsons uses four interrelated systems

("sub-systems of human action")

to analyse this

human

reality: the

biological system, the

personality

system, the

cultural

system

and the

social system

Parsons identifies four especially important empirical "clusterings"

of social

structure: 1)

Kinship,

sex and

socialisation

[family] -

2)

Stratification

of occupational roles

[class] - 3)

Power, force

and

territory [

State,

politics] - 4)

Religion and similar systems

of orientation and

adjustment. (See

Parsons, T. 1951 page 152).

Parsons says

social systems

have four

needs which correspond to parts of the social

structure.

Three of these fit in with

Hegel's

division:

adaptation (relating to

the economy),

goal attainment (relating to

politics) and

latency (relating to

the family). Parsons's

fourth need is

integration, which he relates to

religion.

Four sub-systems of social action

See

Parsons

Social systems have a

structure - which can be represented as

a diagram of their parts. But the system is

dynamic, it moves. It is also comparable to a

living organism in that it has needs.

Four empirical structural clusters

Four needs

| Playing the creativity ball game: Starting with society - individual - government - we went through solidarity - social - suicide - peer-pressure - drugs - prison - to social glue - division of labour - social view (looking at things Weber's way) - conformity - state of nature - naturist - nudist - rebel - conformity - deviance - religion - anomie - conflict theory - disagreement - anarchy. We discussed the relationship of anarchy to the theories of Hobbes, Locke, Weber and Durkheim. We asked what would give an anarchist society solidarity and whether the state increased or decreased individual freedom. |

Sociology: The science of society. See Durkheim and Weber's Contrasting Imaginations: Who is the Sociologist?. The original French word (Sociologie) was created by Comte in 1839 and there is a sense in which sociology was invented in France. .

The

Emerson timeline (external link -

archive) puts the

term in context. The

French Wikipedia contains (or contained) the disputed claim the

the term dates back to 1788/1789. This appears to be incorrect.

The similarly constructed word "Psychology", for the science of mind, had existed in English since the late 17th century.

External links to Wikipedia articles on:

on Sociology on Anthropology

on Sociology on Anthropology

At one time of consultation, Wikipedia said "Sociology is the study of social rules and processes that bind and separate people not only as individuals, but as members of associations, groups, and institutions." Then adding as a "typical textbook definition" the "study of the social lives of humans, groups and societies". Durkheim argues that sociology is the scientific study of society: Of the real social forces that contrain our individual actions (social facts).

Thinking Sociologically

"Thinking sociologically" is an approach that starts from meaningful

individual perceptions and actions rather than the reality of society

(which may be disputed). It is a Weberian as distinct from a

Durkheimian

approach. Bauman and May write "individual actors come into the view of

sociological study in terms of being members or partners in a network of

interdependence... how do the types of social relations and societies that

we inhabit relate to how we see each other, ourselves and our knowledge,

actions and their consequences?... to think sociologically is to make

sense of the human condition via an analysis of the manifold web of

human interdependency..

(Bauman, Z. and May, T. 2000 pages 5 and 9)

In the United States of America, beliefs about

society

tend to use

State of

Nature

theory as axioms. USA

Sociology

explores the idea that

individuals construct society, without

always

recognising that to do so is a product of particular

societies, at

particular times.

A

"general statement" "intended to develop a unified conceptual

scheme for theory and research in the social sciences" was published by

nine USA social scientists in 1951. Theory was to be based on a "theory of

action" in which "the point of reference of all terms is the action of an

individual actor or collective of actors".

Social

Science is a broader concept than

sociology. It includes all the sciences with social content,

including psychology, politics, economics, human geography, anthropology,

etc. The term dates from the late nineteenth century. Older terms with a

similar meaning include sciences humaines (human sciences - a

French

term dating back to the 17th century) - sciences de l'homme

(sciences of man) - sciences morales et politiques (moral and

political sciences - See

1770 and

1795) -

moral sciences, a term

used by J.S. Mill in

1843 and by

Cambridge University in 1851

See

Porter and Ross 9.2003

"Moral

Statistics" is another term where "moral" may mean social rather

than ethical. In the term

"moral insanity", moral can mean behavioural

or emotional rather then to do with the intellect.

See also natural science

and social science

| Anthropology | 1841 - 1843 |

Anthropology means the scientific study of human beings. For a time in the 18th and 19th centuries it tended to mean the study of human physical characteristics, but has been extended to cultural and social characteristics. It is the science of humankind in the broadest sense. (See man).

Ethnology is a mid-nineteenth century term for the science of nations or races. The Ethnological Society, founded in London in 1843, became The Anthropological Society in 1863. In the United States, a New York based American Ethnological Society was started in 1842. A Bureau of Ethnology was established by an Act of Congress in 1879 and the Anthropological Society of Washington at the same time.

James Cowles Prichard wrote in his The Natural History of Man (1843, p.132) "The history of nations termed ethnology, must be mainly founded on the relations of their languages". The Etnografiske Museum opened in Copenhagan, Denmark in 1849.

Anthropology has tended to theorise about the evolution of human beings, physically and culturally and to take a cross cultural approach. There is no strict division between anthropology and sociology, they overlap.

Some well known studies of society that are based on anthropology are Engels' The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), Durkheim's The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912), and Freud's Totem and Taboo (1913).

These are based on studies of pre-literate societies. In the twentieth century however, the scope of antthropoloy was extended to all societies. Robert Park wrote, in 1925

"Anthropology... has been mainly concerned... with the study of primitive peoples. But civilised man is quite as interesting... Urban life and culture are more varied, subtle, and complicated, but the fundamental motives are in both instances the same. The same patient methods of observation which anthropologists... have expended on the study of the life and manners of the North American Indian might be even more fruitfully employed in the investigation of the customs, beliefs, social practices, and general conceptions of life prevalent ... on the lower North Side in Chicago..."

anthropo comes from the Greek anthropos for human being.

ethno, from the Greek ethnos for nation, is used in combination for

nation, people or culture. So, by a strange convolution, one gets

ethnomethodology, in sociology, which is a method of theoretical

analysis of individuals constructing and maintaining the social order

(culture?) of

everyday situations - Like coping with the complex

negotiations of meaning involved in buying a newspaper from a newspaper

stall.

More straightforward: ethnography (writing about race) is used for the scientific description of nations, races or peoples, with their different customs. Utah State University has a collection of student ethnographies online from a field trip to Peru. In 2000 a joural to link anthropology and sociology was launched with the title Ethnography. See also ethnicity

Ethnography is, nowadays, more often used for studies of culture/s. See Wikipedia. See autoethnography

Anthropometry Measurement of the height and other dimensions of

human beings, especially at different ages, or in different races,

occupations, etc.

Anthropomorphic Shaped in human form

Social in the

social sciences, since the mid-19th century, relates

to the mutual relationships of human beings (as individuals or classes) and

is connected with the functions and structures necessary to membership of a

group or society. (Oxford English Dictionary)

Social: Relating to society. Relating to people in society. Relating to the

public as a whole. (Definition based on a

1900 Dictionary)

Social dimension

Erving Goffman (1961) writes of the

"social beginning of the patient's career" as distinct from the

psychological

beginning of ... mental illness.

The Social Dimensions of Scientific Knowledge

| Social System: | See society and society's parts - Parsons on society's parts |

The

Social System is one of Parsons' four

sub-systems of human action. The social system specialises

in the function

of

integration.

In a social system parts are arranged in a pattern of relationships that, together, makes the system.

See Talcott Parsons' 1942 definition

Talcott Parsons argues that each of us is an actor playing a role within a system of relationships. He analyses the real (concrete) system we are in into social system, cultural system and our own personality system. (Extracts)

" a social system consists in a plurality of individual actors interacting with each other in ..." [an environment]... whose relation to their situations, including each other, is defined and mediated in terms of a system of culturally structured and shared symbols." (Parsons, T. 1951 p.5)

Human relationships being made by means of symbols, links Parsons' system

theory to the theories of the

symbolic interactionists. Both also, use

role as a key concept. The two bodies of

thought are, arguably, complementary - With

structural

functionalism concentrating on analysing social structure, and

symbolic interactionism analysing everyday social interaction at social-

psychology level. See

the argument of C. Wright Miils that social science should be

the study of the intersection within social structure of personal

biography

(and everyday social interaction) and history.

Parsons argues that "Every social system is a functioning entity". It is

a system of interdependent structures and processes such that it tends to maintain a relative stability and distinctiveness of pattern and behaviour as an entity"

In some ways, its behaviour is analogous to an organism.

(

1954 Essays, p.143)

Social System Needs:

Talcott Parsons says that

societies (like all

systems and

organisms)

have needs which must be fulfilled if they are to survive.

- "...process in any social system is subject to four

independent

functional imperatives or "problems" which must be met

adequately if

equilibrium and/or continuing existence of the system is to be

maintained."

(Parsons and Smelser 1957 p.16)

Social system needs - functional needs - functional imperatives - all seem to refer to the same things: Things a system requires if it is to stay alive and thrive. These needs exist because of the system's relationship with its environment and because of the internal working of the system.

Parsons says that

all societies have four basic needs:

Every

social system must adapt - set goals - integrate -

and provide for its latent needs. The initials AGIL are often used

to help us recall these four needs.

A social model could be thought of as a

paradigm for

understanding that emphasises

social factors.

The European Social Model is used to describe the European experience of

simultaneously promoting sustainable economic growth and social cohesion

See social models of disability -

health -

distress

See analysis of

Society's parts by Parsons

|

|

Able -

disabled

Thomas Betterton wrote in the 17th century that "the hands are the most

habil" [able] "members of the body". The word able comes from a word

meaning "to hold".

Someone who is able to do something has the "skill, qualities, knowledge,

means, or opportunity to do it" (Plain English Dictionary)

Disable - disabled

To disable is to "make incapable of action or use". With respect to people

it is to "deprive of physical or mental

ability, especially through injury

or disease". (Oxford English Dictionary. Late 15th century origins)

Amelia Harris's definitions

Amelia Harris needed to create definitions that would enable the Department

of Health and Social Security to survey (count a sample) disabled people

for the first time. The definitions she used were:

Impairment: "a) lacking part of or all of a limb, or b) having a defective

limb, organ or mechanism of the body which stops or limits getting about,

working, or self-care".

Disablement: "the loss or reduction of functional ability".

Handicap: "the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by permanent

disability".

The sample of 12,738 people interviewed, between October 1968 and February

1969, was selected on the basis of impairment. One of the objects of the

survey was to discover to what extent impairment led to handicap. On the

basis of the survey, it was estimated that

Finkelstein's social interpretation of disability

Impair: make worse, as in "medication impaired his judgment".

Impairment

Impairment may refer to a medical condition that leads to

disability

Physical impairment

Victor Finkelstein uses a

definition of (physical) impairment

which he takes from definitions used by

Amelia Harris of the Department of

Health and Social Security:

Physical, mental or sensory impairment

A broader definition has also been created:

Social model

of disability

The social model of disability

emerged from the disabled people's movement.

It distinguishes

impairment from disability.

Apart from difficulties a person may experience as a result of an

impairment, they can expect to experience additional problems as a result

of the societal response to it. The problems due to the societal response

are called disabilities. The social model, therefore, locates the problem

of disability in society, while recognising potential problems of

actual/perceived impairments or complex relationships between the two.

(Beresford, Nettle and Perring, Research survey notes)

Social model of

health and

illness

The

social model of health is an extension of the

social model of

disability. It is a different concept from the

social

approach. Like the

social model of disability it draws a

distinction between individual

impairment and a disabling society.

The individual may experience or be seen to have an impairment. However,

disability is the negative social response

to such perceived impairments.

Social model of madness

and

distress

This has been proposed by

Peter Beresford Mary Nettle and Rebecca Perring in

Towards a Social

Model of Madness and Distress? Exploring What Service Users

Say (2010).

Participants in the discussions reported made a number of points:

Oppression

can result in

psychological distress. The solution should not be

medication, but a change in the

norm of social

relationship. So, for example, that

children have more power and that

men and women have more

equal relationships. (p.16)

A social model of distress would respect the expertise,

experience and insight of those when suffer the distress. It would

listen

to individual experience rather than forcing people into a pattern. (p.18)

The social model challenges a previously dominant

medical

model by placing

emphasis on a social and political context and highlighting experiences of

discrimination and exclusion (p.19)

A social model means that we will not agree to be good mental health people

who

take our medication every day, but will be proud psychiatric survivors who

challenge the notion that something is wrong with us and argue that

something is wrong with the society that will not accept

us. (p.24)

The biopsychosocial model of disability

The

World Health Organisation argues that

"The medical model views disability as a feature of the person, directly

caused by disease, trauma or other health condition, which requires medical

care provided in the

form of individual treatment by professionals...

"The social model ... sees disability as a socially-created problem...

On the social model, disability demands a political response, since the

problem is created by an unaccommodating physical environment brought about

by attitudes and other features of the social environment.

Disability is

always an interaction between features of the person and features of the

overall

context in which the person lives, but some aspects of disability are

almost

entirely internal to the person, while another aspect is almost entirely

external. In

other words, both medical and social responses are appropriate to the

problems

associated with disability; we cannot wholly reject either kind of

intervention.

A better model of disability, in short, is one that synthesizes what is

true in the

medical and social models, without making the mistake each makes in

reducing

the whole, complex notion of disability to one of its aspects.

This more useful model of disability might be called the

biopsychosocial model

Constitutional rule is limited - by

laws

or by the will of those who are ruled, for example.

Absolute rule (or absolutism) is the

converse of constitutional. It means that a rule is not

limited.

The word absolute comes from being absolved (set free) of the

bonds of responsibility. This is the meaning of free in title of King

James's book

The True Law of Free Monarchies (1598).

The absolute monarch is free of the

constraints of

law: "having absolute power; arbitrary, despotic" (New Shorter Oxford

Dictionary). This political use of

the word absolute started in the

late 16th century. The theory of absolute monarchy developed

fully in the

17th century. The final end of absolute monarchy (and the

establishment of constitutional monarchy) in Britain was

1688, but in France it was not until

1789.

From the start, some theorists of political absolutism

(Filmer, for

example)

modelled their arguments on the family where a benevolent father

had powers given to him (by God or nature) to rule over his wife and

children.

The family was the

model for political society.

Criticising both the political and the family model,

John Stuart Mill wrote

Absolute and words with similar meanings

There are many words used by theorists to describe

absolute rulers or rulers similar to them. These include

autocrat (self + rule)

despot;

dictator and

tyrant.

tyrant and tyranny also imply that the rule is oppressive or

cruel. See, for example, the use of the term by

Cesare Beccaria and by

John Stuart Mill

despot Originally Greek for master or

lord. A late 19th century dictionary defines despot as "a ruler...

exercising

absolute

power in a state, irrespective of the wishes of the subject"; and despotic

as both absolute and arbitrary government. Arbitrary government is by the

will of the ruler, without regard for rules or laws. It is capricious and

unpredictable.

Durkheim compares despotism to childhood:

"A despot is like a child; he has a child's weaknesses because he is not

master of himself. Self-mastery is the first condition of all true power,

of all liberty worthy of the name. One cannot be master of himself when he

has within him forces that by definition, cannot be mastered."

Whilst Locke separates despotic power from family (paternal) power

(see above), John Stuart Mill applies the

concept "despot" to the rule of men in families, at least when it is based

only on their being men. See

Mill index

dictator From the

Roman magistrate appointed in time of crisis);

A dictator is usually taken to refer to an individual who has

absolute power (or behaves as if he or she ought to have)

Karl Marx used it for a stage in history, "the dicatorship of

the proletariate", when he predicted that the working

class

(proletariate) would exercise absolute power over society

(including

other classes) before the society changed into a classless society. (See

Marx

8.3.1852

Academia

The world of academics; the academic environment or community. (Oxford

English Dictionary)

See also power.

Ability and

disability have also been associated with

wholeness and blemish. See

Leviticus

"There are some three million impaired men and women in Great

Britain (aged 16 and over, living in private households), just over a

million of whom are handicapped. Twenty-five thousand are so severely

handicapped as to need constant care or supervision every day and

practically every night, a further 132,000 needing constant day-care. Of

these 157,000 very severely handicapped, some 26,000 men and nearly 90.000

women, are aged 65 or over, two thirds of them being at least 75 years

old."

(Harris, A.I. 1973, p.56)

"To my mind the cause (or 'source') of

disability is

social.

That is,

society through its social relationships (both,

inter-personal - the

roles

people play; and physical - the buildings and environment where

these roles are played) disables its people who have physical

impairments.

Consequently to eliminate disability it is necessary to change these social

relations - that is, we, disabled people, must all participate in the

changing of society. It is obvious that this is a major task and cannot be

achieved if we are confused about what we have to do. It is therefore

important to make clear where some of the 'experts' go wrong, where they

are confused or where they mystify the nature of the problem

(disability)."

"In my earlier argument I concentrated on showing that

disability is not caused by the physical condition of a person's

body.

Theories which use this

concept as the basis for a definition of disability

are using what various 'experts' have called the

'medical model'. With this

approach the cause of our social difficulties is seen to be in our physical

condition. If this could be 'cured' then our social problems would be

eliminated. Since, at present anyway, not all physical impairments can be

'cured', those who use the

'medical model' of disability usually end up by

talking about the necessity for 'adjusting' to disability, 'accepting' our

limitations, or saying that not every disabled person can be integrated,

etc. "

(Finkelstein 3.1975)

"lacking part of or all of a limb, or having a defective limb,

organ or mechanism of the body."

(Finkelstein 1.1975 and 3.1975, from

Amelia Harris

"an impairment is the limitation of a

person's physical, mental or sensory function on a long term basis."

If something is absolute it is total or complete.

Jock Young

distinguishes between

absolutist and relativist models of society.

Absolute or Constitutional

"Whether the institution to be defended is ...

political absolutism, or

the absolutism of the head of a family ... we are presented with pictures

of loving exercise of authority on one side, loving submission to it on the

other - ... Who doubts that there may be great goodness, and great

happiness, and great affection, under the absolute government of a good

man? Meanwhile, laws and institutions require to be adapted, not to good

men, but to bad. Marriage is not an institution designed for a select few.

Men are not required, as a preliminary to the marriage ceremony, to prove

by testimonials that they are fit to be trusted with the exercise of

absolute power"

Locke distinguishes paternal

from political and from despotic power. In Locke's theory, one

gains natural, political, freedom, on becoming an adult able to control

one's own life. However, natural freedom can be

forfeited (lost because of

an offence). When this happens, society's power over the offender becomes

despotic.

| Accommodation | See also Adaptation and Assimilation |

Accommodation has several meanings relating to fitting needs. We speak of a place to live as accommodation because it provided for us and our belongings. But its oldest meaning is human beings adapting themselves to one another's needs. A man who cannot fit in with other people cannot "accommodate himself to anyone". Similarly, it can be applied to other things that should be capable of fitting in. Our eyes, for example, alter themselves in order to see things at different distances. Another way of saying this is that "eyes have the power of accommodating to different distances".

Accommodation (altering ourselves) is one way of adapting to our environment. Another way is assimilation.

|

Action

Agency |

See also

Interaction and

Symbolic Interaction

Circumstances surround action. |

Max Weber wrote: In action is included all human behaviour when and in so far as the acting individual attaches a subjective meaning to it.

Meaning The meaning of something is what it refers to or stands for. We can ask the meaning of something when what we seek to find is how it can be explained. In this sense, Herbert Hawkins speaks of trying "to find a meaning" in one's observations. This relates to the significance or importance of something, to how we understand something as part of an overall system of thought or theory.

The other (and original) meaning of meaning, relates to intention. If you mean to do something, you intend to do it. Meaning and action are intimate relations.

Behaviour contrasted with

Action

When you blink, it is behaviour, you intend nothing, it

has no meaning, it is not an action. If you wink you intend something, it

is not just behaviour, it is action.

Social Action

Blinking: the involuntary closing and opening of the eyelids that happens

all the time that we are awake.

Winking: Closing one eyelid briefly as a signal to someone else,

perhaps to suggest that what you have said is a joke, or has a hidden

meaning.

See subjective - See

reflex arc

"

Action is social in so far as, by virtue of the

subjective meaning attached to it by the

acting individual (or individuals), it takes account of the

behaviour of others and is thereby

orientated in its course."

|

Weber said that:

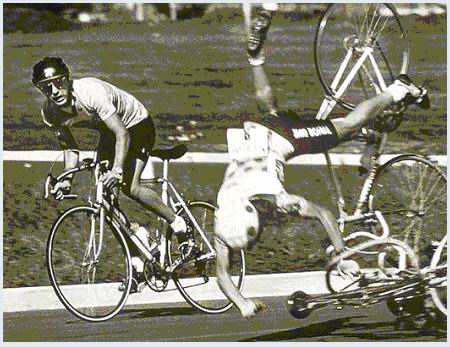

a collision of cyclists may be compared to a natural event. their attempt to avoid hitting each other following the collision, would constitute social action |

Action Frame of Reference

Talcott Parsons

began his theory

(1937) with the "Action Frame of Reference", a development of

the "Voluntaristic Theory of Action" that he saw as developing in social

theory. He then moved on

(1951)

to analyse of

social systems in terms of the action frame of reference.

At some time in 1950, Parsons and eight other

USA Social Theorists reached agreement on a

General Statement respecting concepts for a

"Theory of Action". They wrote that "In accordance with already widespread

usage, we shall call these concepts the frame of reference of the theory

of action"

| See Habermas on Communicative Action |

| Actor | See both action and role |

Someone who acts - that is does things with intent, meaningfully, as distinct from behaving without meaning. (See action).

Another word for actor, in this sense, is agent: Someone who does something.

How does action relate to

social structure? Think of action and you probably think of

people freely choosing to do things. How does that happen if the structure

of society is deciding what they do? Relating action to structure is what

is meant by the "problem of

agency and structure".

Actor can also mean role-playing - as actors do on a stage.

Agency as autonomous self-determined action:

Agency can mean the ability of an individual or group to act for herself, himself or itself. If not allowed to do so s/he/it is lacking in agency, or denied agency. Someone who can only act if s/he does what someone else says lacks agency.

Arguing that someone is not the real author of a work s/he wrote because s/he was influenced, taught, or helped by someone else is to deny their agency.

I base the above on the geekfeminisim wikia.

Agency as autonomy, plus more:

Agency as autonomy seems to fit the meaning in the following quotations, but other features are added.

"The exercise of human agency is about intentional action, exercising choice, making a difference and monitoring effects" Chris Watkins, 2005, "Classrooms as learning communities" p. 47, basing himself on Dietz and Burns (below)

"effective, intentional, unconstrained and reflexive action by individual or collective actors" (Dietz and Burns 1992: Abstract)

"invitation into participatory spaces is not enough for individuals to act with agency to influence and claim their rights to quality health care" (Renedo and Marston 6.2015 p.491)

Adaptation - Adjustment - Accommodation - Assimilation

To adapt is to alter to make fit for use. To adjust is to arrange things so

that they fit together or harmonise. Accommodation is (usually) human

beings adapting themselves to one another's needs. Assimilation is to take

in or absorb something.

Adaptation in biology and ecology

Robert Park says that The term adaptation came into vogue with Darwin's theory of the origin of the species by natural selection. As this suggests, adaptation is a term relating to the way an organism alters itself in relation to its environment. [See Introduction to Darwin's Origin of Species]

Jean Piaget applies this to the psychological development of human beings.

Piaget argues that we have mental structures that adapt (alter) in response to challenges the environment presents to our activities. Schema are elements of these structures. They are variable ways of acting which have a common feature. For example, we grasp different objects with different muscle movements, but there is an overall plan of acting.

The adaptation of a mental structure is a two-sided process. The two sides are accommodation and assimilation. In accommodation, the existing schema is altered in order to adapt to a new element in the environment. In assimilation, the new object of experience is incorporated into the existing schema.

The two processes take place together. An example is a child who can grasp large objects, but not small ones. To learn to grasp small ones, s/he has to attempt to grasp them: This is attempting to assimilate the small object into the existing grasping technique. In doing so, however, the technique will need to be modified: That is, it will accommodate to the new task.

Park and Burgess

Park and Burgess also make use of the three concepts of adaptation,

accommodation and assimilation. (See

Ecology). They do so in a different way to

Piaget. They use adaptation for the unconscious biological

alteration of organisms in relationship to one another, and

accommodation

for the conscious alteration of human beings in realtion to one another.

Assimilation is a more thoroughgoing form of accommodation. Through

intimate

relationship, people come

"into possession of a common experience and a common tradition"

Talcott Parsons' Adaptation

Adaptation (he maybe thinking of the adaptation of the society

to its

environment) is one of the

four basic needs that

Parsons says that all

Social Systems

have. All societies need a

mechanism to allocate resources. In the social system as a

whole, this is

done by the

economy.

Parsons also says that adaptation is a specialist function of the

organism

In Hegel's analysis

of

society, the economy is rooted in

civil society, which includes

the judicial

and police system that make transactions possible.

See also

Political Economy

Erving Goffman's two types of adjustment

Goffman defines two types of adjustment of people to

institutions. Primary adjustments are ones that harmonise the

individual with the institution on the way that is intended. Secondary

adjustments are habitual ways in which people get round the

organisation's assumptions about what they should do and be. The totality

of such secondary adjustments is an organisation's

underlife

In 1599,

William Shakespeare (aged about 37), defined the seven ages of

man as roles he plays. This could be regarded as a

sociological view of age - One that inter-relates the

biological and psychological. In

1964,

New Society used the

Seven Ages concept for a series of articles surveying "the development of

man - his body,

his personality, his

abilities.

Shakespeare wrote:

All the world's a stage,

age one: infant The "nurse" in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet is a

wet-nurse employed to suckle Juliet who continues to care for her after she

has finished

breast-feeding.

Understanding other people's speech develops gradually from about six

months.

Producing one's own words begins about age one, and then develops rapidly.

There is a "vocabulary explosion" in the middle of the second year.

"Grammatical rules and word combinations appear at about age two. Mastery

of vocabulary and grammar continue gradually through the preschool and

school years."

(Wikipedia) - (See

Piaget

and representational thought)

age two: school boy If Shakespeare attended the "King's New Schoool"

in Stratford, he would have done so between the ages of seven and fourteen.

Child labour:

A British Act of 1842 stopped children under ten years old

working underground in coalmines. A

series of Acts between 1870 and 1918 made education free and

compulsory for children from five years old to ten, then to eleven, then to

fourteen. Education provided for the "childhood" period is known as

elementary or primary.

age three:

lover. Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway in November

1582, when he was 18 years old and Anne 26 years old. She was already

pregnant with their first child.

Adolescence just means growing up. It is the passage from childhood

to adulthood. In many cultures, it is marked by social "rites"

(ceremonies)

"of passage". Examples are the Bat Mitzvah (aged 12) of Jewish

girls and Bar Mitzvah (aged 13) of Jewish boys. Before these ceremonies,

the parents are responsible for the morals of the child, through the

ceremonies, the child assumes responsibility for her or his life in the

community. Puberty is the period during which adolescents reach

sexual maturity.

age four: soldier

age five: justice

age six: pantaloon a rich, greedy, rather foolish, old man in

Italian comedy.

The menopause typically occurs in women during their late 40s or

early 50s. Commonly called the change of life. During this the

menstrual cycle ceases and the woman is no longer able to conceive babies.

The social and psychological component of the "change of life" is

demonstrated by the idea of the "male menopause". Although there is no

corresponding biological change in men, people speak of a corresponding

stage in a man's life marked by a crisis of identity and confidence.

age seven: sans everything Shakespeare died on 23.4.1616, just

before his 54th birthday. Anne died 6.8.1623, aged 67 years. Some people

have calculated the average lifespan of an adult male in Elizabethan

England as 47 years,

(Wikipedia)

Psalm 90 in the

1611

Bible calculates "the days of our years" as seveny-five, or

eighty if we are strong

Making the Case for the Social Sciences No. 2 - Ageing

20.7.2010

"adaptation is applied to organic modifications which are transmitted

biologically; while accommodation is used with reference to changes in

habit, which are transmitted, or may be transmitted, sociologically, that

is, in the form of social tradition"

For

Habermas, this is part of the

system integration

Economy and Civil Society

Age

See

subject index

And all the men and women merely players,

They have their exits and entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the

infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse's arms.

Then, the whining

schoolboy

with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the

lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress' eyebrow. Then a

soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden, and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon's mouth. And then the

justice

In fair round belly, with good capon lin'd,

With eyes severe, and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws, and modern instances,

And so he plays his part. The

sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper'd pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose, and pouch on side,

His

youthful hose well sav'd, a world too wide,

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again towards childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound.

Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

See

Childhood and

Childabuse

New Society 1964: Infancy: 0 to 5

New Society 1964:

Childhood: 6 to 12

The term youth (the time when one is

young) is often used particulary for the period between childhood and full

adulthood.

New Society 1964: Adolescence: 12 to 18

Education provided for the adolescence period is known as secondary

Under the UK's

1944 Education Act, secondary education was compulsory

and free for (almost) all children from eleven years to

fifteen years (from 1947) and then 16 (from 1973). The stage beyond

secondary education is not compulsory. It can be referred to as

tertiary (third level)

New Society 1964: Young Adult: 18 to 30

University level education ("higher" education in the UK) generally

begins at 18. It can begin earlier or at any later age

New Society 1964: Prime of Life: 30 to 42

New Society 1964: Middle Age: 42 to 60

New Society 1964: Old Age: Beyond 60

UK statistics

|

Country is a

Raymond Williams

keyword. He points out that it has two broad meanings. I can

speak of "my country", meaning the land or

nation I belong to. But I can also speak of the country as rural

rather than

urban areas, as in "town and country". It is, perhaps, to avoid

confusion that we now use the word countryside for rural areas.

Ager is French for field. So the word argiculture means cultivating fields. Agriculture is farming, including growing crops and rearing animals for food. Rural comes from the Latin word ruralis which means of the countryside. |

| Sociologia Ruralis is the journal the European Society for Rural Sociology. The society is based in Holland. It was founded in 1957 and its journal started in 1960. website |

|

|

Once upon a time, almost everywhere was countryside. Today, most

of the world is still countryside, but about half of the world's population

lives in urban areas. That half still lives on the food which is mainly

produced in the countryside.

The village is part of the countryside. A town may be a market town that serves the countrside. Modern cities have almost lost sight of the countrsyside. |

Alienate - Alienation -

Estrange - Estrangement

These words mean to make someone or something a

stranger or foreigner to

us. The meaning can stretch from stripping someone of

citizenship and

making him or her an outcast to just selling something. If you sell your

mobile phone, it is no longer yours. You have alienated it. Another meaning

of alienation is to be separated from one's sane being, or to be mad.

See

essay on Rousseau. Can we sell ourselves? Can we become slaves

voluntarily? In this essay, Mohammed Elsadek argues that alienation is a

central concept in the thought of

Jean Jaques

Rousseau. We could think of it as providing the movement

(dynamics) to his social theory. Humans are alienated from society and the

movement comes from our efforts to restore our humanity.

See

essay on Marx and

Engels - Estrangement or alienation. What do we lose of

ourselves when we sell our labour? Following

Hegel (who followed

Kant, who followed

Rousseau), alienation or estrangement is a central concept of the work of

Marx and Engels in the

1840s. Scholars have different views of its later importance,

What are we alienated from? According to Marx

A similar idea was expressed by Elsie Davenport in 1948

See William Morris in

News from Nowhere in 1890

See

Thinking Sociologically the Bauman

and May way

Egoism is the older word - Although it only dates back to the late

eighteenth century. It is from ego, the Latin for I. It means the same as

when people say "me - me - me - me - me"! It is about selfishness or

following self interest in opposition to other peoples interests.

Social theories developed from

Hobbes are egoistic. They assume that following individual self

interest is natural and that what needs to be explained is how self

interest can be restrained enough to make society possible. So,

Herbert Spencer, who writes in the tradition of Hobbes, says

Altruism is a word formed by

Auguste Comte in 1851, to talk about benevolent, in contrast to

selfish inclinations.

Two great schools of sociology, one built on

Hobbes and the other on

Rousseau, can be distinguished by whether they consider altruism

a real,

solid aspect of human nature. Following the tradition of Rousseau,

Emile

Durkheim wrote:

"the productive life is the life of the species. It is life-

engendering life. The whole character of a species, its species- character,

is contained in the character of its life activity; and free, conscious

activity is man's species-character."

(1844 manuscripts)

"Man is by nature a creative artist... a community deprived of

the opportunity to create with hands as well as with brain, becomes ill-

balanced and ultimately unsound... The machine... must produce things in

large quantities, and all to the same pattern... while it might be

impractical to design and make one's own car... when you have woven your

own cushion square... it will possess an individual character which no

machine could produce" (Davenport 1948)

"

Altruism - Egoism

"The promptings of egoism are duly restrained by regard for

others." (quoted in the Shorter Oxford Dictionary)

"altruism is not destined to become, as Spencer desires, a sort of

agreeable ornament to social life, but it will forever be its fundamental

basis"

(Durkheim 1893 p.228)

Anarchy

From Greek for without a chief.

As a political fear, anarchy is chaos. Thomas Carlyle wrote:

"Without sovereigns, true sovereigns, temporal and spiritual, I see nothing possible but an anarchy; the hatefullest of things."

But there is also a political theory that sets it out as an ideal. Geoffrey Keith Roberts in his book on Anarchy defines it as:

"The organisation of society on the basis of voluntary cooperation, and especially without the agency of political institutions, i.e. the state."

The quotations are from the Oxford English Dictionary

Animism

"The theory which endows the phenomenon of nature with personal life might

perhaps conveniently be called 'animism'"

(E.B. Tylor

"Religion of Savages" 1866)

Art -

skill - craft - a

trade

(occupation)

- artist -

artiste - artisan

|

Art is

a Raymond Williams

keyword. In practice, the use of words such as art, artisan, and

trade tends to be related to

class as much as to

creativity.

In its original meaning, art refers to any kind of skill.

1768 See

Royal Academy of Arts

1887 Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, formed in London

1890 William Morris

News from Nowhere -

"I hear that you are a weaver I should like to ask you something about that

craft,"

1893 artisan,

plain, and superior household cookery

["Ladies desirous...]

|

|

1900 Dictionary: artisan and artist and

artiste all come from the same Latin root but

artisan means "one skilled in any art or trade; a handicraftsman; a mechanic" artist means "one skilled in art or profession, especially, one who professes and practices one of the fine arts, as painting, sculpture, engraving, and architecture; specifically and most frequently, a painter. artiste (a French word) means "one who is particularly skilful in any art, as a public singer, an opera dancer, and even a cook". craft (an old English word) means cunning, art or skill [generally] and [specifically] dexterity in a particular manual occupation. A craftsman is an artificer, a mechanic, one skilled in a manual occupation. 1911 Enfield Trade School 1931 Hornsey School of Arts and Crafts

|

|

1943 Artistes at Enfield (drama and singing)

1948 Crafts Centre of Great Britain

Articulate

To articulate is to put different articles (items) together in a form.

Articulate

speech is a good formation of words.

To re-articulate is to put different articles (items) together in a

different form. The items are rearranged.

Aryan

In the wake of

national socialism, aryan is a highly contentious term.

Following the Wikipedia link above and examining the struggle over the term

there (see discussion page, for example) may indicate how contentious it

is.

I have included Walter Theimer's, critical,

1939 dictionary entry on Aryans in the file on National

Socialism

Max Müller,

in 1861, speaks occasionally of an Aryan race (pages 213, 245,

246, 256). More often, he uses terms like the "Aryan family of

speech". He made clear

in 1888 that his use of Aryan was as a cultural rather than a

biological concept:

"Aryas are those who speak Aryan languages, whatever their

colour, whatever their blood. In calling them Aryas we predicate nothing of

them except that the grammar of their language is Aryan"

| Assimilation | See also Adaptation and Accommodation |

Assimilation is to take in or absorb something. Assimilate means to make similar.

Used of a living organism - it means to take in external material and convert it into fluids and tissues identical with the organism's own fluids and tissues. This is what we do when we eat and drink, and also when we breath.

In plants, the process of photosynthesis assimilates carbon dioxide from the air and, using sunlight, converts it into the carbon compounds (sugars, for example) that the plant is made of. Animals assimilate these compounds when they eat the plants and convert them into animal tissues. In this way, the carbon compounds of all living things are created.

The word is also used for absorbing, and making our's own, ideas and influences. We assimilate ideas when we make them part of our own way of thinking or acting. We assimilate information when we take it in and understand it fully.

In relation to migration, assimilation is "the process through which an ethnic minority takes on the values, norms, and the ways of behaving of the dominant, mainstream group and is accepted by the latter as a full member of their society" (Fulcher and Scott 2007, p.857).

| Authority |

See also legitimacy

authoritarian and authoritarianism |

The Plain English Dictionary says that "If someone has authority over a group of people, they have the legal right or power to tell them what to do"

Authority is a special kind of power. It is not just force. The word's origins are linked to ideas of God as the "author" of our being.

There is something magical about authority and many social theorists have discussed its special qualities as a key to understanding society. (See, for example, Rousseau, Weber, Freud and Scruton)

|

Authority is the right to enforce obediance. A crook

with a gun may

have the power to force you to obey, but does not have the

authority to do

so.

Hobbes argued that submitting to force can create a duty to obey, but Rousseau replied:

|

We tend to say that a government has authority if is legitimate.. This is the way that Max Weber defines authority as a type of power. He says:

"the legitimate exercise of imperative control... is.. authority"Authority and arbitrary power

Authority can be contrasted with reason. This appears to be what Mary Wollstonecraft does in Vindication of the Rights of Woman, chapter one, where she is discussing "The Rights and Involved Duties of Mankind". She says

"any ... maxim deduced from simple reason, raises an outcry - the Church or the State is in danger, if faith in the wisdom of antiquity is not implicit; and they who ... dare to attack human authority, are reviled as despisers of God and enemies of man"

Here, authority is the people in power, and it is associated with what Max Weber called "traditional authority" and Wollstonecraft calls "the wisdom of antiquity".

Wollstonecraft is supporting what we might call the "authority of reason". She associates (traditional or established) authority with arbitrary power. Arbitrary power is not governed by reason (See absolutism). She associates reason with the power of the people, when informed by the free discussion of ideas, and says:

"when once the public opinion preponderates, through the exertion of reason, the overthrow of arbitrary power is not very distant"

Authority is an old

English word, coming from French and Latin after 1066 (the Norman

conquest). Authoritarian (late 19th century) and authoritarianism are

relatively new words. Authoritarian means in favour of obedience - in

politics, the family, or wherever. An authoritarian style of government is

called authoritarianism.

Here is the definition of Authoritarian from a 1939 Political Dictionary

(English). In 1939, Italy (Fascist) and Germany (Nazi) were proud to be

authoritarian:

Authoritarian and authoritarianism

"Authoritarian: a term denoting a more or less

dictatorial system of government, as opposed to the

democratic system based on the people's sovereignty. Adherents

of authoritarianism criticise the alleged disunion and inefficiency of the